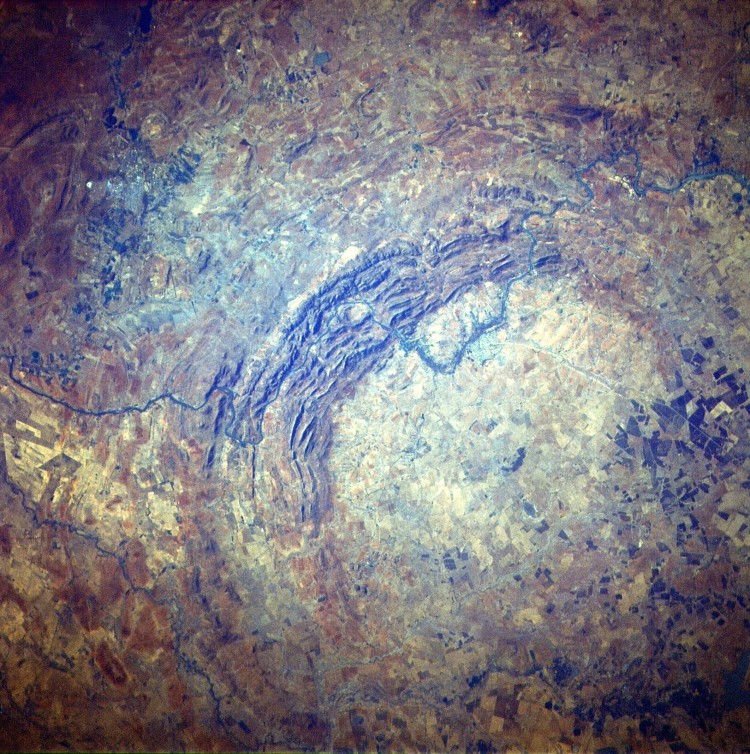

Vredefort crater – remains of the largest verified impact crater on Earth, more than 300km across when it was formed. Free State Province, South Africa

There are aspects of this article with which I disagree, but that the author advocated for uncertainty is, I think, most important.

***

David Malone, ‘Can we learn to love uncertainty?,’ New Scientist, 04.08.07, 46-47

You might think that no one could argue with the value of certainty. It has the air of one of those indisputably good things, like world peace or motherhood. But I would argue that the pursuit of certainty has become a dangerous addiction. Like alcohol, it makes us feel safe, but it is also making us stupid and belligerent.

Few notions have become as deeply embedded in our culture as the belief that there is a perfect certainty to be had – and the desire to have it. It has survived virtually intact the transition from religion to rationalism as the touchstone of our society. Even as science squeezed out belief in God and scriptural certainties, a perfect law-governed creation remained; it was just under new management. Science has become, in the minds of many, the new guarantor that there is certainty and that we can attain it.

We are faced with all kinds of questions to which we would like unequivocal answers. Do mobile phones cause cancer? Does depleted uranium? Is global warming real? There is a huge pressure on science to provide concrete answers when the alternatives are cant and self-serving opinion.

But the temptation to frame these debates in terms of certainty is fraught with danger. Certainty is an unforgiving taskmaster. It may seem prudent to say that when the scientists are certain then we’ll know what to do, but it is a mere step from there to say we should do nothing until we are certain.

As every climate scientist knows, there will always be facts that won’t fit even the best model of global climate. That’s the nature of models and the weather – and it illustrates just how badly we can be led astray by the fiction that science is about certainty. If we are honest and say the scientists’ conclusions aren’t certain, we may find this being used as justification for doing nothing, or even to allow wriggle room for the supernatural to creep back in again. If we pretend we’re certain when we are not, we risk being unmasked as liars.

The very word ‘uncertainty’, along with ‘incompleteness’ and ‘uncomputability’, encapsulates one of the three of the most profound theories in 20th-century science and mathematics. Yet they are all defined in terms of the unsettling lack of something positive or better. It is perhaps for that reason that the stories of those who discovered these uncertainties have been largely overlooked.

This is why I made Dangerous Knowledge for BBC television: to champion the incomplete, the uncomputable and the uncertain.

In a society desperate to find certainty, and beset on all sides by people who claim to have it, this seems like a suitable moment to show that the idea of certainty-from-on-high was discredited 100 years ago. I wanted to tell the stories of the people who made this discovery and the great personal price they paid. A line of thinkers from Georg Cantor to Alan Turing saw the extent of the uncertainty in science, and incompleteness in logic and mathematics, and understood what we still haven’t grasped as a culture. I am fascinated by just how reluctant we are to face up to what these heroes revealed.

What is also striking is how much of 20th-century history has been defined by a disastrous oscillation between two equally hopeless reactions to the perceived loss of certainty. At one extreme, if the things we think are true can’t be underpinned with certainty, we declare that nothing can be true and make a bonfire of all certainties. Think fin-de-siècle Vienna or Weimar Germany or even the postmodernist stance, which becomes the perfect apologists’ creed for the status quo.

At the other extreme, think of the absurd and deranged certainties of Hitler’s Reich and Stalin’s five-year plans, or the cold-war doctrine of mutually assured nuclear destruction. And all this, ironically, at a time when Kurt Gödel and Turing were busy destroying the dream of absolute certainty.

We have still not really absorbed their ideas. Turing in particular laid bare the profundity and seriousness of incompleteness and uncomputability, using his invention, the computer, to show how deep and pervasive our inability to know for certain is. As it turned out, his invention overshadowed his conclusion and, ironically, for the past 50 years the computer has be seen as the certainty engine – the machine that can solve the problems we can’t. What we failed to notice is that the computer has actually made us less certain: we now know, for example, that we cannot precisely model weather, climate or the economy, and very probably never will.

The computer has turned out to be like every other industrial process: designed to turn out something desirable through the front door but with an unintended by-product, a ‘pollution’, emerging from the back door – in this case, uncertainty. Non-linear mathematics, the butterfly effect, emergent phenomena, all revealed by the computer, add to the incompleteness of logic and conspire to make certainty elusive.

We need to reach an accommodation with uncertainty. Not only is the universe uncertain, but so too is human knowledge. Science as a process should never have fostered any illusions about this: it was always about provisional truths and knew it.

Perhaps it’s time for us to finally accept that we shouldn’t believe in science because we think it certain, but precisely because it’s not.

Certainty is totalitarian. It forecloses further thinking, Not one of the theories devised by Newton, Darwin, Einstein or Planck is certain and perfect. Powerful and beautiful they undoubtedly are, but they are still partial and incomplete approximations of truth.

For the modern counterparts of Gödel and Turing – the likes of Roger Penrose and Gregory Chaitin – intellectual certainty is a dead end. Serious thinkers are not afraid of uncertainty. For them a theory’s uncertainty or incompleteness is not a failing but a positive and creative condition in is own right. The profound discoveries of modern mathematics and science show that life and thinking flourish only in the liminal and fertile land that lies between too much certainty and too much doubt. The art of scientific inquiry is to tack back and forth between the two.

More than ever, science needs to remember the words of Bertrand Russell: ‘Uncertainty, in the presence of vivid hopes and fears, is painful, but must be endured if we wish to live without the support of comforting fairy tales…To teach how to live without certainty, and yet without being paralysed by hesitation, is perhaps the chief thing.’

Thanks for sharing. And the words of Bertrand Russell – I absolutely agree with it.

Have nice day!

Arcane owl

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Arcane Owl,

Russell had many good things to say. I hope you have a good day too!

Phil

LikeLiked by 1 person