Category Archives: Neoplatonism

The world is nothing but matter in motion

Now that the ideological caravans of modernism and post-modernism have run out of steam, what next? Mysticism? But this is a very hot potato – for two reasons: the primary Western form – Neoplatonism – has been treated by generations of academics as the pornography of modern Western philosophy, even as its Siren call has been eagerly responded to, particularly by male philosophers, and its profound influence on their work dissembled about or denied. To explore mysticism in this regard threatens to undermine gods, expose ideologically motivated lies, damage careers and lay bare a cultural arrogance and self-delusion that we in the West are the champions of (the Man of) ‘Reason’ while others stare at their navels or are obsessed with filial piety and particularly, as Marx recognised, its contradictory core, now absorbed by him into materialism, is nothing but revolutionary. It rings the bell for the passing of all and everything but matter in motion itself – it speaks of a mobile infinity.

Why I am not a Marxist – my response to ‘God’s Last Stand’

Philip Stanfield /26.12.20

Why I am not a Marxist – my response to ‘God’s Last Stand’

I enjoyed reading ‘God’s Last Stand’ by Corinna Lotz and Gerry Gold (both, I presume, Marxists) and I particularly appreciated their call for the development of materialist dialectics. They first presented this essay in 1995 and I should note that Lotz has stated recently that her ‘own understanding has moved on considerably’ since then, as many discoveries have been made in science, particularly in the area of neuroplasticity and, to use Lotz’s expression, ‘the “embodied” mind’. Their writing on a difficult subject – dialectics – is clear and consistent, with good examples.

What do they call for?

Lotz and Gold call not merely for Marxists to develop ‘a contemporary theory of materialist dialectics’ but for that development to be ‘revolutionary’, a ‘quantum leap’ reflecting revolutionary advances in modern science, such as quantum mechanics, astrophysics and consciousness studies, and particularly to counter critics of the materialist world view such as Paul Davies – as Engels countered Dühring in Anti-Dühring (and, I add, Lenin later countered subjective idealism in Materialism and Empirio-criticism).

Further, giving added urgency to their call, not only have advances in knowledge of brain structure produced a new ‘theory of mind functioning’, they write that Oliver Sacks talked of a crisis in scientific understanding, arising from an ‘“acute incompatibility between observations and existing theories.”’

Initial criticisms

While I strongly agree with their call for the development of dialectics and praise them for that, it is peculiar that a call for a ‘revolutionary’ development by Marxists – why only Marxists? – should be coming from Marxists, all of whom should be familiar with dialectics – with what is only revolutionary, and nothing but revolutionary. The first lesson of dialectics, like time and tide, is that its engine, contradiction, with its own laws, waits for no one. The call by Lotz and Gold is a very strong criticism of present Marxists generally.

Lotz and Gold write ‘The end of Stalinism has dealt a devastating blow to those who turned Marxism from a method of discovery into a prescriptive dogma’ but make no mention of the relationship between dialectics and socialist revolution, writing only of those in science. They write ‘A key issue for Marxists is the development of consciousness in the working class movement.’. The key issue for Marxists, as I understand, is socialist revolution, for which a developed consciousness in the working class is essential. In a conversation last year, on Youtube, in which Lotz discusses democracy, she not once spoke of ‘socialism’ or ‘revolution.’ Lotz and Gold look forward to how new concepts emerging from scientific developments might be applied to our understanding of class relations, ‘to represent a new world order’ but make no mention of how this new world order is to be achieved.

In response to Lotz and Gold asking ‘Does (the breakdown of the Soviet Union) mean that all the previous history suddenly vanishes, as some crude impressionists have suggested? Surely it shows the need for a more complex and dynamic understanding of the process of historical negation enriched by new concepts, such as Prigogine’s’, I quote Engels worthy words on the production requirements for socialism

‘Since the historical appearance of the capitalist mode of production, the appropriation by society of all the means of production has often been dreamed of, more or less vaguely, by individuals, as well as by sects, as the ideal of the future. But it could become possible, could become a historical necessity, only when the actual conditions for its realisation were there. Like every other social advance, it becomes practicable, not by men understanding that the existence of classes is in contradiction to justice, equality, etc., not by the mere willingness to abolish these classes, but by virtue of certain new economic conditions. The separation of society into an exploiting and an exploited class, a ruling and an oppressed class, was the necessary consequence of the deficient and restricted development of production in former times. So long as the total social labour only yields a produce which but slightly exceeds that barely necessary for the existence of all; so long therefore, as labour engages all or almost all the time of the great majority of the members of society – so long, of necessity, this society is divided into classes.’1

It is a matter of not only developing dialectical logic but also of applying what has already been developed, correctly.

For Lotz, Gold and Stephen Hawking to refer to such a fool as Wittgenstein (Heraclitus without the Heraclitus) – so beloved by and useful to time-serving academic philosophers on behalf of their capitalist masters – to exemplify that ‘20th century philosophers have failed to keep up with the advance of scientific theories’ fails utterly to support what should be a claim extremely easy to illustrate.

Why I am not a Marxist

I am not a Marxist in the same sense that I do not subscribe primarily only to the particular work of Plotinus or Proclus or Cusanus or Hegel. I do subscribe to the philosophical current initiatedby Plotinus, that was always open to development, and has been taken, so far, furthest by Marx in dialectical materialism. Just as Hegel is not recognised specifically as the consummate Neoplatonist, which I have argued in my thesis ‘Hegel the Consummate Neoplatonist’2 – a small but growing number – including Marx3 and Engels4 – refer to him merely as a ‘mystic’ or to his philosophy as ‘mysticism’ – so Marxism and dialectical materialism are not recognised as part of this continuum.

To subscribe only to the extent that any of the above originated (in the case of Plotinus) or developed that current in philosophy is to imply there is a limit on a philosophy which seeks to reflect that which has no limit and one absolute – change. There was a long history of development within Neoplatonism prior to Marx, culminating in Hegel’s objective (‘absolute’) idealism (with Hegel, Neoplatonism had, in a sense, gone full-circle), without which Marx could not have taken the next, logical step, incorporating it into materialism, taking materialism from mechanical to dialectical. Engels not only acknowledged developments within idealism and materialism but wrote that materialism, too, must change its form.5 With the ever-deepening of our knowledge of the world, dialectical materialism, too, will in turn develop beyond Marxism, into new, presently unimaginable forms.

Much is made by Marxists – and a false line of separation deliberately created – of Marx’s standing Hegel’s philosophy ‘right way up’, on material feet, but this current was always about the unity of the ‘world’ in motion, and development within the ‘world’ through contradiction. What is necessary is to take that current further, not as an ’ist’ or a ‘ian’, but as one who embraces its core of driving contradiction, unending motion and ceaseless change.

To be able to do as Lotz and Gold think is necessary would require recognising the place of Marxism on the continuum initiated by Plotinus – a recognition that Engels not merely failed to have, but emphatically rejected – they quote him both in the blurb to their essay and, in Italics, in the essay itself: ‘That which still survives, independently of all earlier philosophy, is the science of thought and its laws formal logic and dialectics.’ The way forward is to recognise and acknowledge this continuum and then to both look at the strengths, flaws and weaknesses in what has been carried over into Marxism from mysticism and to reflect our deepening knowledge of the world in the development of dialectical logic and practice.

Neoplatonism and dialectical materialism

) the world:

The impact of Neoplatonism (the primary form of Western mysticism) is everywhere in Western culture, particularly (as should be expected) in the area of artistic creativity. Its vitalism informed – and informs – a break from all scholastic pedantry.

While Marx’s famous ‘inversion’ of Hegel’s philosophy represented a rejection of philosophical idealism, Marx did not reject but absorb into materialism the fruits of its long developmental heritage in idealism, culminating in Hegel’s philosophy – a necessary prior development that prepared the ground for, that enabled that logical next step.

Hegel’s ‘point of departure’ that Engels referred to in his Dialectics of Nature 6 was that of Plotinus. Armstrong wrote

The material universe for Plotinus is a living, organic whole, the best possible image of the living unity-in-diversity of the World of Forms in Intellect. It is held together in every part by a universal sympathy and harmony, in which external evil and suffering take their place as necessary elements in the great pattern, the great dance of the universe…Matter then is responsible for the evil and imperfection of the material world; but that world is good and necessary, the best possible image of the world of spirit on the material level, where it is necessary that it should express itself for the completion of the whole. It has not the goodness of its archetype, but it has the goodness of the best possible image.7

It was Plotinus who, in arguing for the beauty and worth of the earth and everything on it set the philosophical basis for the Neoplatonists’ keen interest in the world, which Cusanus exemplified brilliantly in Book II of De docta ignorantia and which, later, Hegel exemplified in the second book of his Encyclopaedia.

Lotz and Gold wrote of ‘the essential unity and interconnectedness of all matter’. So did Plotinus. His second hypostasis Intellectual-Principle is the universe of Spirit, the unity-in-multiplicity of Divine Mind and of all ‘minds’. Everything that is in the sensory universe – including ‘matter’, now immutable – is in this universe, but mutually inclusive, far more alive and eternal.

The same failure to recognise the achievements of Plotinus in Cassirer’s praise for Cusanus8 Engels made in his praise for Hegel

For the first time the whole world…is represented as a process, i.e., as in constant motion, change, transformation, development; and the attempt is made to trace out the internal connection that makes a continuous whole of all this movement and development9

Hegel, as did Cusanus, drew on Plotinus

Let us then apprehend in our thought this visible universe, with each of its parts remaining what it is without confusion, gathering all of them together into one as far as we can, so that when any one part appears first, for instance the outside heavenly sphere, the imagination of the sun and, with it, the other heavenly bodies follows immediately, and the earth and sea and all the living creatures are seen, as they could in fact all be seen inside a transparent sphere. Let there be, then, in the soul a shining imagination of a sphere, having everything within it, either moving or standing still, or some things moving and others standing still. Keep this, and apprehend in your mind another, taking away the mass: take away also the places, and the mental picture of matter in yourself, and do not try to apprehend another sphere smaller in mass than the original one, but calling on the god who made that of which you have the mental picture, pray him to come. And may he come, bringing his own universe with him, with all the gods within him, he who is one and all, and each god is all the gods coming together into one; they are different in their powers, but by that one manifold power they are all one; or rather, the one god is all; for he does not fail if all become what he is; they are all together and each one again apart in a position without separation (my italics), possessing no perceptible shape – for if they did, one would be in one place and one in another, and each would no longer be all in himself…nor is each whole like a power cut up which is as large as the measure of its parts. But this, the [intelligible] All, is universal power, extending to infinity and powerful to infinity (my italics); and that god is so great that his parts have become infinite (my italics)…’ 10

Lotz and Gold draw on a staple from mysticism (in the part is the whole), writing ’This is a beautiful concretisation of the dialectical concept of how the universal finds its expression within the individual. Within the development of each individual mind is expressed not an abstract universal, but “a universal which comprises in itself the wealth of the particular, the individual, the single”. Plotinus wrote in his tractate ‘Nature, Contemplation, and the One’, translated by Creuzer in 1805

(In) the true and first universe (of Intellect)…each part is not cut off from the whole; but the whole life of it and the whole intellect lives and thinks all together in one, and makes the part the whole and all bound in friendship with itself, since one part is not separated from another and has not become merely other, estranged from the rest; and, therefore, one does not wrong another, even if they are opposites. 11

) contradiction:

Lotz and Gold wrote ‘the movement of mutually exclusive opposites…is the essence of dialectics’. This essence derives from The Enneads in which it is the means of return to unity with God.

They wrote ‘Engels’ great contribution to dialectics is his advancing of the intrinsically correct concepts of the Greek ancient philosophers about the nature of matter and motion. These are viewed as an indivisible unity and conflict of opposites.’ Engels wrote in Anti-Dühring ‘dialectics has so far been fairly closely investigated by only two thinkers, Aristotle and Hegel.’12 Engels was completely incorrect – other than Hegel’s philosophy, Marx and Engels were ignorant of (due to no interest in) Neoplatonism.13

To exemplify both the extent of Engels’ error in making this assertion and the keen interest and pleasure the Neoplatonists took in contradiction – the engine, as Lotz and Gold write, of dialectics – and how superior the Neoplatonists were to Aristotle in this regard (on whom they also drew very significantly), Cusanus can speak for them:

NICHOLAS: I laud your remarks. And I add that also in another manner Aristotle closed off to himself a way for viewing the truth. For, as we mentioned earlier, he denied that there is a Substance of substance or a Beginning of beginning. Thus, he would also have denied that there is a Contradiction of contradiction. But had anyone asked him whether he saw contradiction in contradictories, he would have replied, truly, that he did. Suppose he were thereupon asked: “If that which you see in contradictories you see antecedently (just as you see a cause antecedently to its effect), then do you not see contradiction without contradiction?” Assuredly, he could not have denied that this is so. For just as he saw that the contradiction in contradictories is contradiction of the contradictories, so prior to the contradictories he would have seen Contradiction before the expressed contradiction (even as the theologian Dionysius saw God to be, without opposition, the Oppositeness of opposites; for prior to [there being any] opposites it is not the case that anything is opposed to oppositeness). But even though the Philosopher failed in first philosophy, or mental philosophy, nevertheless in rational and moral [philosophy] he wrote many things very worthy of complete praise. Since these things do not belong to the present speculation, let it suffice that we have made the preceding remarks about Aristotle.14

) subject and object:

Lotz and Gold wrote of the subject/object relation – ‘the essential contradiction in the dialectics of cognition’. The development in The Enneads, too, is based on this relation. Noting the ‘strange phenomenon’ of a distinction in one self, Plotinus continued

Unless there is something beyond bare unity, there can be no vision: vision must converge with a visible object. …in so far as there is action, there is diversity. If there be no distinctions, what is there to do, what direction in which to move? An agent must either act upon the extern or be a multiple and so able to act upon itself: making no advance towards anything other than itself, it is motionless, and where it could know only blank fixity it can know nothing.15

Not only must there be diversity but that diversity must be identity as well

The intellective power, therefore, when occupied with the intellectual act, must be in a state of duality, whether one of the two elements stand actually outside or both lie within: the intellectual act will always comport diversity as well as the necessary identity16

In describing Hegel’s method, Magee unintentionally summarised the Neoplatonic position

when the subject wishes to know itself, it must split itself into a subjective side, which knows, and an objective side, which is known.17

Areas of potential development

Lenin began ‘On the Question of Dialectics’ ‘The splitting of a single whole and the cognition of its contradictory parts…is the essence…of dialectics.’18 This is what I advocate regarding ‘dialectical materialism’ itself. What are its contradictory parts, the cognition of which, through testing in practice, can enable further development? The Neoplatonic heritage of dialectical materialism should be acknowledged and then fully examined, both refining or, if found wanting, rejecting any elements that detract from the development of dialectics.

) ’reason’:

What is ‘reason’? Philosophers have the least understanding of the practice they most pride themselves on. Is it simply a chain of conscious, linguistic thought leading to a conclusion? The leading Marxists all dismissed mysticism (although its method is the philosophical core of their epistemology – now there’s a contradiction for anyone interested!…). Lenin, with his aptitude for energetic language, referred to it as ‘the very antechamber of fideism’.19 Lotz and Gold make a clear distinction between ‘reason’ and mysticism. They write of Davies’ ‘road to mysticism…due entirely to his eclectic method’ of his ‘mystical fog’, and ‘web of religious mysticism’. They discount the central importance of mysticism to Marxism and dialectical materialism.

Marxist logic not only derives from Neoplatonism, more generally, it is rooted in Western thought with its limitations – great emphasis is placed on patriarchal language and concepts (clearly defined – i.e. bounded and limited, and therefore potential vehicles for control, no matter how useful to knowledge), and Western supremacism (other cultures and modes of thinking are disparaged), of which Hegel, the renowned master of ‘Reason’ is a fine example

Negroes are to be regarded as a race of children…The Mongols…spread like monstrous locust swarms over other countries and then…sink back again into the thoughtless indifference and dull inertia which preceded this outburst. …(the Chinese) have no compunction in exposing or simply destroying their infants.

It is in the Caucasian race that mind first attains to absolute unity with itself. ..and in doing so creates world-history.

The principle of the European mind is, therefore, self-conscious Reason…In Europe, therefore, there prevails this infinite thirst for knowledge which is alien to other races. …the European mind…subdues the outer world to its ends with an energy which has ensured for it the mastery of the world.20

The time is long overdue for the Man of Reason with his narrow, patriarchal dualisms that Lloyd and particularly Plumwood exposed so well to be got rid of. I am not aware that Marxists enquire regarding possible forms of reason (different from the consciousness studies Lotz and Gold referred to) which do not function conceptually.

Engels wrote that for Hegel, ‘only dialectical thinking is reasonable’ – i.e. ‘reason’ that ‘presupposes investigation of the nature of concepts themselves…’21 Yet of Hegel, to whom concepts were so important, Engels wrote that he had absolutely nothing to say about the ultimate concept in his conceptual system – Absolute Idea.22 Engels also believed that dialectical thought required the investigation of concepts.

Dialectical reasoning can take two forms – it can be done both consciously (using language) and subconsciously (using intuition). It is not necessary to have definite, conscious thought in order to reason dialectically. A profound contradiction in The Enneads on the relationship between ‘reason’ and intuition remained, though much more thoroughly worked out, in Hegel’s philosophy. On the one hand he wrote that to reason we require language and concepts, on the other, as a Neoplatonist, he justified intuition. Marx ‘solved’ that ‘problem’ by simply raising the banner of ‘science’ and ignoring intuition and the reality of sub-conscious dialectical reason. The only dialectical reason for him and Engels is conscious and conceptual.

In his Philosophy of Mind Hegel wrote that the body is only the ‘mind’s’ first appearance, while language is its perfect expression.23 In his Science of Logic he wrote ‘The forms of thought are, in the first instance, displayed and stored in human language.’24 He believed we cannot think without words (although he also wrote, very interestingly, we are thinking all the time, including in sleep25) and that words give our thoughts their highest and truest existence which only becomes definite when we objectify them

(The existence of words) is absolutely necessary to our thoughts. We only know our thoughts, only have definite, actual thoughts, when we give them the form of objectivity.26

For Hegel, along this path, what cannot be expressed in language has no reality. But the path beginning with intuition can cater for both conscious and sub-conscious dialectical reason and Hegel wrote about this excellently.

) intuition:

I contend that reason can be done subconsciously, dialectically, and one can consciously observe that process. Intuition is itself dialectical, non-linguistic, rich, wholistic, fluid and instantaneous. It is tied more deeply than conscious reason to our emotions. What the concept represents has been dismissed as ‘the feminine’. Both Plotinus and Hegel believed an intuition to be the unity of subject and object, in a dialectical relationship. Both Plotinus and Hegel distinguished between ‘mindless’ (sensuous consciousness) and ’mindful’ (thinking religiously) intuition. Plotinus correctly wrote that ‘we are continuously intuitive but we are not unbrokenly aware.’27 Hegel echoed this, writing ‘Mindless intuition is merely sensuous consciousness which remains external to the object.’28

Of ‘mindful’ intuition Hegel wrote that it

apprehends the genuine substance of the object. ……It is, therefore, rightly insisted on that in all branches of science, and particularly also in philosophy, one should speak from an intuitive grasp of the subject-matter.29

This process begins with a Neoplatonic unity of thinking in which there is no distinction (which Hegel calls ‘immediate intuition’) then, inspired ‘with wonder and awe’ by the object, the philosopher engages in cognising it, stripping away ‘the inessentials of the external and contingent,’ employing ‘the pure thinking of Reason which comprehends its object…(possessing) a perfectly determinate, true intuition.’ This is the Neoplatonic process of emanation and return – from unity to distinction between subject and its object in the process of the latter’s cognition, to unity again in the source, but now made ‘true (my italics) intuition.’30

Hegel wrote intuition forms only the substantial form into which (my italics) (the) completely developed cognition concentrates itself again. In immediate intuition, it is true that I have the entire object before me; but not until my cognition of the object developed in all its aspects (my italics) has returned into the form of simple (my italics) intuition does it confront my intelligence as an articulated, systematic totality.

Recognise that intuition and this process are material and based in praxis and you have excellent philosophy – I have an intuition, I think about it conceptually as thoroughly as possible, testing it and my reasoning about it – and conclude the process having cognised that intuition in its fullness (having reasoned conceptually to a conclusion on the basis of practice what arose from my sub-consciousness).

Weeks wrote about Kepler (who referred to Cusanus as ‘divine’ in his Mysterium Cosmographicum published in 1596 and 1621)

Johannes Kepler regarded his initial intuition concerning the structure of the solar system to be a divine revelation of the divine plan of creation. Hence, his intuition can justifiably be called mystical. But in pursuing this intuition, he proceeded as a scientist and mathematician, not as a mystic.31

To pursue an intuition conceptually and dialectically is one path, but the other, which the Neoplatonists valued most is subconscious and far more creative. Magee discussed Hegel’s method for this, which he described as mytho-poetic circumscription (which method echoed the inspired poetic style of Plotinus in his Enneads, so beautifully translated by Stephen MacKenna)

Hegel rejects propositional thought, which would define the Absolute, and instead ‘talks around’ or ‘thinks around’ the Absolute, revealing at each point some aspect or part of it. The totality of Hegel’s philosophical speech is the Truth, the Absolute itself.32

Just as concepts (particularly the hypostases themselves) were stepping-stones to be ‘thought around’ for Plotinus and the Neoplatonists prior to Hegel, from and to spiritual unity with their highest concept the One-Absolute, so Hegel, following particularly Plotinus, Proclus and Cusanus used his concepts in the same way from and to spiritual unity with his God/One/Absolute. What makes Hegel’s philosophy ‘mythical’ is his overlay of the Christian myth across his Neoplatonism.

Inevitably Hegel employed the devices of poetry including images, metaphors and symbols – myth, in Christian form, being the most important of them – Christian mythology provided Hegel with images, metaphors and symbolism.

Hegel’s argument is borne by the dense mystical tapestry he wove using concepts as focal or anchor points. He wrote that speculative thinking (which concept he noted the Neoplatonists equated with ‘mystical’33) is from one point of view akin to the poetic imagination and he used words and concepts to create a rationalised feeling for the Absolute, rather than to attain a literal cognition of it. In his philosophy, God comes to know himself Neoplatonically – most importantly, he does so dialectically.

While Plotinus did think that intuition is the immediate unity of subject with its object, with that unity, as for Hegel, comes knowledge. Plotinus equated intuition with knowledge and that knowledge, held with the highest degree of Neoplatonic consciousness, is attained after a complex process of dialectical thinking – along either path.

Having had an intuition, I can leave it to its own subconscious processes. For it to work, I must not interrupt (attempt to control) it although I can sense and feel its development, which can continue during ‘sleep’ (what is ‘sleep’?), leading to a conclusion. Who hasn’t woken to the ‘Eureka!’ moment they couldn’t achieve with conscious reason – precisely because it is restricted to concepts, allowing no space for trotting chairs and fluttering wings.34

) a review of the relationship between Neoplatonism and dialectical materialism:

> concepts

>> (In addition to the points I have discussed through this essay) Get rid of everything already in dialectical logic that undermines it and contradicts ‘matter’ (objective reality), e.g ‘mind’ – a concept which Lotz and Gold used (‘the functioning of the mind’, ‘a theory of mind which is both materialist and dialectical’) as did Marx, Engels and Lenin. To write of ‘mind’ together with materialism is a contradiction in terms. ‘Mind’ is a Trojan horse for philosophical idealism into materialism (‘mind of God’ etc., etc.). I can show you a brain. Who can show me a mind?

>> While contradiction and negation is the developmental pathway for the Neoplatonist and Marxist, does the goal of the former – ‘the greatest activity in the greatest stillness’ (unity with the One) have a parallel in any way with ‘classless’ communism (need I acknowledge the concept is not Neoplatonic?)?

Hegel’s Absolute Idea is understood to ‘contain’ all the preceding categories, as, in effect, Absolute’s definition. Such a claim, even though it is putting Hegel’s view, should be exposed – as Engels did (describing it as the reactionary aspect of Hegel’s philosophy). From one of the greatest dialecticians, it is the attempt to impose a final definition on a process which is without end, and in which such a concept and definition has no part. The same provisional and inadequate definition of the Absolute by the categories in their dialectical development should apply no less to ‘Absolute Idea.’’ ‘Communism’ carries the same overtones of finality, of an ultimate unity.

>> the application of new concepts resulting from scientific developments (Lotz and Gold give examples of this). Research should go on re- unacknowledged forms of (potential) reason (intuition, dreaming, guided dreaming) and brain functions regarded as ‘below’ (‘more primitive than’) conscious reason. For Marxists in particular, what should be of primary importance, advocate the necessity of socialist revolution and its relevance to all the above.

In conclusion: I agree with Lotz and Gold’s words ‘The key issue is to go beyond the unscientific…and actually discover…(what) must be integrated into an advanced dialectics of nature.’

***

Notes

1. Frederick Engels, Anti-Dühring, Herr Eugen Dühring’s Revolution in Science (henceforth cited as A-D), Progress, Moscow, 1975, 333-334

2. Engels wrote in the rough draft of the ‘Introduction’ for his Anti-Dühring ‘The Hegelian system was the last and most consummate form of philosophy, in so far as the latter is represented as a special science superior to every other. All philosophy collapsed with this system.’ Frederick Engels, A-D op. cit., 34, note. On Engels’ latter point, my position is that when one thinks of philosophy as the posing of the most disruptive questions (as I curiously heard an academic philosopher define it once), there will never be an end to philosophy or the need for it.

3. ‘I therefore openly avowed myself the pupil of that mighty thinker…The mystification which the dialectic suffers in Hegel’s hands by no means prevents him from being the first to present its general forms of motion in a comprehensive and conscious manner. With him it is standing on its head. It must be inverted, in order to discover the rational kernel within the mystical shell.

In its mystified form, the dialectic became the fashion in Germany, because it seemed to transfigure and glorify what exists. In its rational form it is a scandal and an abomination to the bourgeoisie and its doctrinaire spokesmen, because it includes in its positive understanding of what exists a simultaneous recognition of its negation, its inevitable destruction; because it regards every historically developed form as being in a fluid state, in motion, and therefore grasps its transient aspect as well; and because it does not let itself be impressed by anything, being in its very essence critical and revolutionary.’, Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 1, Postface to the Second Edition 1873.

4. Engels wrote of ‘the same laws which similarly form the thread running through the history of the development of human thought and gradually rise to consciousness in thinking man; the laws which Hegel first developed in all-embracing but mystic form, and which we made it one of our aims to strip of this mystic form and to bring clearly before the mind in their complete simplicity and universality.’, A-D op.cit,, 1885 Preface, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1877/anti-duhring/preface.htm#c1

5. ‘just as idealism underwent a series of stages of development, so also did materialism. With each epoch-making discovery even in the sphere of natural science, it has to change its form’ Frederick Engels, Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy (henceforth cited as LF), 1886. Lenin quoted these words in his Materialism: ‘Engels says explicitly that “with each epoch-making discovery even in the sphere of natural science [“not to speak of the history of mankind”], materialism has to change its form” (Ludwig Feuerbach, German edition, p. 19), Materialism and Empirio-criticism, Critical Comments on a Reactionary Philosophy (henceforth cited as MaE), Progress, Moscow, 1977, 232

6. ‘…Hegel’s point of departure: that spirit, mind, the idea, is primary and that the real world is only a copy of the idea.’, Frederick Engels, Dialectics of Nature (henceforth cited as DoN), Progress, Moscow, 1976, 47.

7. A.H.Armstrong in Plotinus, Enneads, Trans., A.H.Armstrong, William Heinemann, London, 1966-1988, vol. I, xxiv

8. ‘From these methodological premises Cusanus arrives at the essential principles of a new cosmology. …the earth may no longer be considered something base or detestable within nature. Rather, it is a noble star…we can see clearly why, from Cusanus’ viewpoint, the new orientation in astronomy that led to the supersession of the geocentric vision of the world was only the result and the expression of a totally new intellectual orientation. This intimate connection between the two was already visible in the formulation of his basic cosmological ideas in De docta ignorantia. It is useless to seek a physical central point for the world. Just as it has no sharply delineated geometric form but rather extends spatially into the indeterminate, so it also has no locally determined centre. Thus, if the question of its central point can be asked at all, it can no longer be answered by physics but by metaphysics.’ Ernst Cassirer, The Individual and the Cosmos in Renaissance Philosophy, Trans., Mario Domandi, Barnes and Noble, New York, 1963, 27. Cusanus explored and brought out through clarification and metaphysical application what was already in Neoplatonic theory. In doing so he made very important contributions to its development and to later science, for example writing in De docta ignorantia ‘the world-machine will have its centre everywhere and its circumference nowhere,’ – long before Hawking, of whom Lotz and Gold wrote ‘By 1988, Hawking concluded: “If the universe is really self-contained, having no boundary or edge, it would have neither beginning nor end. It would simply be. What place, then, for a creator?”’ These contributions were crucial to Hegel’s furthest development of Neoplatonism within idealism.

9. Frederick Engels, A-D, op. cit., 31-32

10. Plotinus, Enneads, Trans., A.H.Armstrong, op. cit., vol. V, V.8.9.

11. Ibid., vol. III, III.2.1

12. A-D op. cit., 392

13. Lenin dismissed the writing of the Neoplatonists as ‘a mass of thin porridge ladled out about God…’, although he contradicted himself with an important reference to Philo on Heraclitus, exemplifying the Neoplatonists’ interest in contradiction, in the first words of his famous ‘On the Question of Dialectics’, Collected Works, Vol. 38 (Philosophical Notebooks), Progress, 1972, 303, 359

14. Nicholas of Cusa, De Li Non Aliud (‘On God as Not-Other’), 1461-2, in Nicholas of Cusa on God as Not-other, Trans., Jasper Hopkins, The Arthur J. Banning Press, Minneapolis, 1999, 1108-1166, 89, 1150

15. Plotinus, The Enneads (Abridged), Trans. Stephen MacKenna, Penguin, London, 1991, V.3.10

16. Ibid.

17. Glenn Alexander Magee,The Hegel Dictionary, Continuum, London, 2010., 69-70

18. Lenin, Collected Works, Vol. 38 op. cit., 359

19. Lenin, MaE, op, cit., 62

20. Hegel, Hegel’s Philosophy of Mind, Part Three of the Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences (1830, henceforth cited as PoM), Trans., William Wallace, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1971, 42-45; ‘Europe, forms the consciousness, the rational part, of the earth, the balance of rivers and valleys and mountains – whose centre is Germany. The division of the world into continents is therefore not contingent, not a convenience; on the contrary, the differences are essential,’ G.W.F.Hegel, Hegel’s Philosophy of Nature, Part Two of the Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences (1830), Trans., A.V.Miller, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 2004, 285; ‘No philosophy in the proper sense (can be found in the Oriental world)…spirit does not arise in the Orient…In the West we are on the proper soil of philosophy,’ Hegel, Lectures on the History of Philosophy 1825-6, op. cit., vol. I, 89, 91

21. Engels, DoN, op.cit., 222-223

22. ‘In his Logic, he can make this end a beginning again, since here the point of the conclusion, the absolute idea — which is only absolute insofar as he has absolutely nothing to say about it – “alienates”, that is, transforms, itself into nature and comes to itself again later in the mind, that is, in thought and in history.’, Frederick Engels, LF, op.cit., Part I: Hegel, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/ 1886/ludwig-feuerbach/ch01.htm

23. Hegel, PoM, op. cit., 147

24. Hegel, Hegel’s Science of Logic, Trans., A.V.Miller, Humanities Press, New York, 1976, 31

25. ‘it is also inadequate to…(say) vaguely that it is only in the waking state that man thinks. For thought in general is so much inherent in the nature of man that he is always thinking, even in sleep. In every form of mind, in feeling, intuition, as in picture-thinking, thought remains the basis.’ Hegel, PoM, op. cit., 69

26. Hegel, PoM, op. cit., 221

27. ‘we are continuously intuitive (my italics) but we are not unbrokenly aware: the reason is that the recipient in us receives from both sides, absorbing not merely intellections but also sense-perceptions.’, Plotinus, The Enneads (Abridged), op. cit., IV.3.30

28. Hegel, PoM, op. cit., 199

29. Ibid.

30. Ibid., 200

31. Andrew Weeks, German Mysticism – From Hildegard of Bingen to Ludwig Wittgenstein: A Literary and Intellectual History, State University of New York Press, Albany, 1993, 8

32. Glenn Alexander Magee, Hegel and the Hermetic Tradition, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 2001, 95

33. ‘The expression ‘mystical’ does in fact occur frequently in the Neoplatonists, for whom (word in Greek) means none other than ‘to consider speculatively’. The religious mysteries too are secrets to the abstract understanding, and it is only for rational, speculative thinking that they are object or content.’, Hegel, Lectures on the History of Philosophy 1825-6 Volume II: Greek Philosophy, Trans., Robert F. Brown and J.M. Stewart, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 2011, 345. Plotinus founded the Western speculative school of philosophy that provided a ‘rational’ account of the mystical, of which school Hegel was its consummate graduate.

34. ‘…The whole night was beset by wings of some sort, and I kept on the go all the time, with my hands and arms protecting my head from these wings. And then – a chair. Not one of our modern chairs but of an ancient style, and wooden. With a horselike gait (right foreleg and left hindleg, left foreleg and right hindleg) this chair trotted up to my bed and climbed up on it; it was uncomfortable, painful – and I loved that wooden chair.

It is amazing: is it really impossible to contrive any remedy against this dreaming disease that would cure it or make it rational – perhaps even put it to some use?’, Yevgeny Zamyatin, We, (1920) Trans., Bernard Guilbert Guerney, Penguin, London, 1984, 126

Some troubling words for those who crave stasis

‘But it is one of the fundamental prejudices of logic as hitherto understood and of ordinary thinking, that contradiction is not so characteristically essential and immanent a determination as identity; but in fact, if it were a question of grading the two determinations and they had to be kept separate, then contradiction would have to be taken as the profounder determination and more characteristic of essence. For as against contradiction, identity is merely the determination of the simple immediate, of dead being; but contradiction is the root of all movement and vitality; it is only in so far as something has a contradiction within it that it moves, has an urge and activity.’

G.W.F.Hegel, Hegel’s Science of Logic, (Vol. I The Objective Logic) Trans., A.V.Miller, Humanities Press, New York, 1976, 439

What is truth?

NGC 2442: Galaxy in Volans

‘Appearance…constitutes the actuality and the movement of the life of truth. The True is thus the Bacchanalian revel in which no member is not drunk; yet because each member collapses as soon as he drops out, the revel is just as much transparent and simple repose. Judged in the court of this movement, the single shapes of Spirit do not persist any more than determinate thoughts do, but they are as much positive and necessary moments, as they are negative and evanescent.’

G.W.F.Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit, Trans., A.V.Miller, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1977, 27-28 (Preface, 47)

![]()

Hegel on the poetry of the world: quantity and quality

‘At first, then, quantity as such appears in opposition to quality; but quantity is itself a quality, a purely self-related determinateness distinct from the determinateness of its other, from quality as such. But quantity is not only a quality; it is the truth of quality itself, the latter having exhibited its own transition into quantity. Quantity, on the other hand…is…quality itself in such a manner that apart from this determination there would no longer be any quality as such. The positing of the totality requires the double transition, not only of the one determinateness into its other, but equally the transition of this other, its return, into the first. …quality is contained in quantity, but this is still a one-sided determinateness. That the converse is equally true, namely, that quantity is contained in quality and is equally only a sublated determinateness, this results from the second transition – the return into the first determinateness. This observation on the necessity of the double transition is of great importance throughout the whole compass of scientific method.’

G.W.F.Hegel, Hegel’s Science of Logic, (Vol. I The Objective Logic) Trans., A.V.Miller, Humanities Press, New York, 1976, 323

Hegel’s ‘Reason’ – the cognition of God who is Absolute Reason

The rose in the Rosicrucian cross is a concentration of mystical meanings including that of unfolding Mind. ‘To recognise reason as the rose in the cross of the present and thereby to enjoy the present, this is the rational insight which reconciles us to the actual…’ Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, Preface.

‘Philosophy in general has God as its object and indeed as its only proper object. Philosophy is no worldly wisdom, as it used to be called; it was called that in contrast with faith. It is not in fact a wisdom of the world but instead a cognitive knowledge of the non-worldly; it is not cognition of external existence, of empirical determinate being and life, or of the formal universe, but rather cognition of all that is eternal – of what God is and of what God’s nature is as it manifests and develops itself.’

*

‘Besides, in philosophy of religion we have as our object God himself, absolute reason. Since we know God who is absolute reason, and investigate this reason, we cognise it, we behave cognitively.’

*

G.W.F.Hegel, Lectures on the Philosophy of Religion Vol. I, Ed., Peter C. Hodgson, Trans., R.F.Brown, P.C.Hodgson, J.M.Stewart, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 2007, 116-7, 170

Hegel’s cultural supremacism and the myth of Western ‘Reason’

The rose in the Rosicrucian cross is a concentration of mystical meanings including that of unfolding Mind. ‘To recognise reason as the rose in the cross of the present and thereby to enjoy the present, this is the rational insight which reconciles us to the actual…’ Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, Preface.

‘(The Oriental spirit) remains impoverished, arid, and just a matter for the understanding. For this reason we find, on the part of Orientals, only reflections, only arid understanding, a completely external enumeration of elements, something utterly deplorable, empty, pedantic, and devoid of spirit, an elaboration of logic similar to the old Wolffian logic. It is the same with Oriental ceremonies.

This is the general character of Oriental religious representations and philosophy. There is, as in their cultus, on the one hand an immersion in devotion, in substance, and so the pedantic detail of the cultus – a vast array of the most tasteless ceremonies and religious activities – and on the other hand, the sublimity and boundlessness in which everything perishes.

There are two Oriental peoples whom I wish to mention, the Chinese and the Indians.’

G.W.F.Hegel, Lectures on the History of Philosophy 1825-6 Volume I: Introduction and Oriental Philosophy, Together With the Introductions from the Other Series of These Lectures, Trans. Robert F. Brown and J.M. Stewart, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 2009, 106

Hegel’s Rose of ‘Reason’ on the Rosicrucian Cross

‘To comprehend what is, this is the task of philosophy, because what is, is reason. …To recognise reason as the rose in the cross of the present and thereby to enjoy the present, this is the rational insight which reconciles us to the actual, the reconciliation which philosophy affords to those in whom there has once arisen an inner voice bidding them to comprehend…’

G.W.F.Hegel, Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, Trans. T.M.Knox, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1979, 11-12

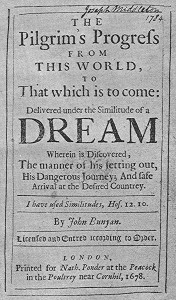

The Pilgrim’s Progress

‘Now, because it has only phenomenal knowledge for its object, this exposition seems not to be Science, free and self-moving in its own peculiar shape; yet from this standpoint it can be regarded as the path of the natural consciousness which presses forward to true knowledge; or as the way of the Soul which journeys through the series of its own configurations as though they were the stations appointed for it by its own nature, so that it may purify itself for the life of the Spirit, and achieve finally, through a completed experience of itself, the awareness of what it really is in itself.’

G.W.F.Hegel, Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, Trans., A.V.Miller, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1977, 49