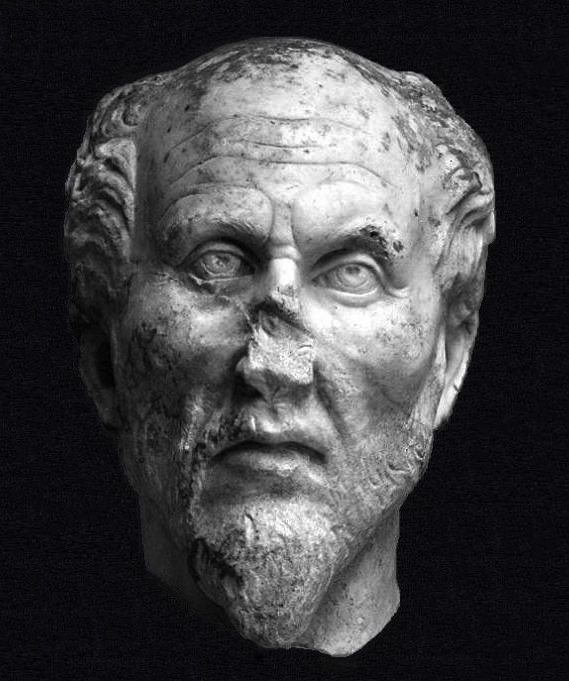

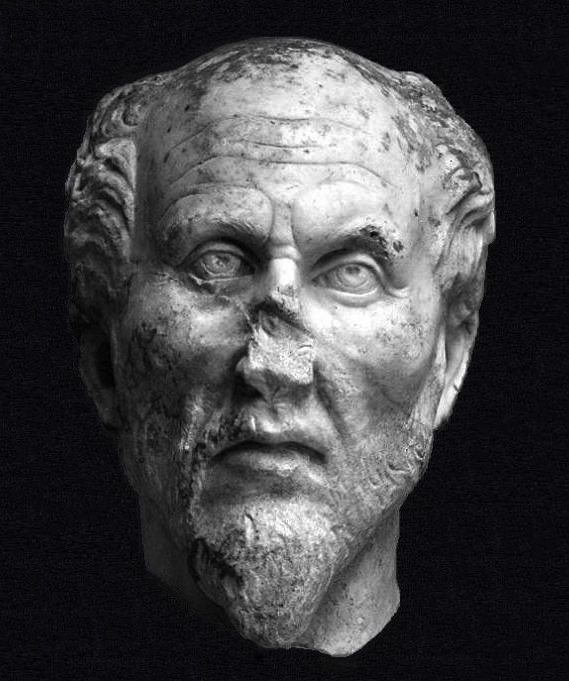

Plotinus (204/5-270), Anonymous, white marble, Ostiense Museum, Ostia Antica, Rome

28.10.1997

Movement and rest in ‘thought’, the most intense activity and stillness in unity

Plotinus, the main expositor of Neoplatonism, was critical of democracy, had friends in the Roman aristocracy, and, despite the rejection of his proposal for the construction of Platonopolis, to be a city of philosophers functioning according to Plato’s Laws, was highly regarded by the emperor Gallienus. His writings, in the Enneads (according to Porphyry, from the age of forty nine), represent his mature thought.

Within this body of pacific austerity, Plotinus’ mysticism builds to a rationalised ecstasy. Reflecting this tension, his equation between contemplation and activity is central to his doctrine. By turning away from the external world1 and an inward concentration of spiritual energy through ‘reason’, the aim of his philosophy was that his soul and the souls of others might re-discover their true self and ascend to union with it and with their common source in god.

Although he was the last great philosopher of Western antiquity, developments on his treatment of spiritual freedom and purpose have continued to the present.2 His work is a blend of the writings of Plato, Aristotle and other Greek philosophers (particularly the Stoics.3 Major sources from his own time were Numenius of Apamea and Ammonius Saccas, of whom he was a pupil. His dominant influence, however, was clearly Plato.

Plotinus was open in his regard for Plato – ‘that godlike man Plato’,4 ‘the illustrious Plato’.5 His debt to Plato, as revealed in the Enneads, was always in his thoughts. He regarded his own writing as following and interpreting Plato’s philosophy, even attributing his mysticism to him.

The Plotinian scholar Paul Henry believes that the continued life of Plato’s philosophy is borne within that of Plotinus, in which dialectic becomes metaphysics – and that as a mystic, Plotinus has been perhaps a greater inspiration for Western philosophy than even Plato himself.6

Such distinctions between Platonic dialectic and Neoplatonic metaphysics are misleading since the differences which exist lie essentially in points of form not in the process of the philosophers’ intent.7 Plotinus developed on a philosophy which itself underwent significant development by Plato. The shift by the latter in his treatment of non-discursive elements (particularly the emotions) in relation to ‘reason’ – first banishing them, then in his later dialogues, allowing them a role in the soul’s aspiration to truth8 – is carried further by Plotinus, in whose philosophy they were central to the attainment of the Good.

Both Plato and Plotinus distinguished between the realm of Ideas beyond time, and the sensible world of matter, existing in time. They also held to a transcendent God, beyond even Ideas and, following from Socrates, both considered the soul to be immaterial and immortal.

One variation between the philosophies of the two men concerns the location of the Forms. For Plato, they exist in the ‘place above the heavens’9 but for Plotinus they are more forcefully tied to the nature of soul. Yet, both in the general inward tenor of his philosophy, and overtly, Plato prepared the ground for Plotinus believing that the Forms can exist within the individual.10

Movement and the tension between it and the Good is central to Plotinus’ philosophy and is considered to be another difference between the doctrines of the two men,11 but again, Plotinus developed on what lay in the work of his predecessor. ‘Thought’s’ double movement of ascent to and descent from the most general concepts of the higher world, around which the Enneads were written, was established in the Republic.12 The importance Plotinus accords to the emotions, in both his style – eager and inspired with spiritual purpose – and in his method, is reflected in the significance movement has in his philosophy. His positioning of vitality and intuition as non-discursive means embodies this.

In order of rank and emanation, the three hypostases around which the Enneads are built are the One (the Good – for which Plotinus frequently used masculine pronouns), Intellect (Divine Mind or Thought – the realm of Forms) and Soul (All-Soul, the Principle of Life). Nature is a quasi-hypostasis. The Gods are frequently mentioned. Beneath the universe of Intellect is the universe of matter. Each hypostasis is inferior to the one preceding it and good to that which follows it, matter having the lowest standing.13

Part one/to be continued…

Notes

1. Porphyry wrote that Plotinus ‘laboured strenuously to free himself and rise above the bitter waves of this blood-drenched life’. Porphyry, ‘On the Life of Plotinus and the Arrangement of His Work’ in The Enneads. Third ed. Abridged. Trans. S. MacKenna. London: Penguin, 1991, cxxi. ↩

2. Ficino’s translation into Latin of Plotinus’ philosophy in 1492 was pivotal to this. (He produced the first Latin translation of all Plato’s dialogues in 1484.) ↩

3.‘In style Plotinus is concise, dense with thought, terse, more lavish of ideas than of words, most often expressing himself with a fervid inspiration. He followed his own path rather than that of tradition, but in his writings both the Stoic and Peripatetic doctrines are sunk; Aristotle’s Metaphysics, especially, is condensed in them, all but entire.’ Porphyry, op. cit., cxii. (Porphyry wrote a [lost] commentary on Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, known to Arab scholars.) MacKenna, consistent with his lyricism, wrote that the Enneads embody the pouring of new wine into very old bottles. See MacKenna’s notes in Plotinus. The Enneads. Third ed. Trans. S. MacKenna. London: Faber and Faber, 1962. ↩

4. Enneads III,5,1. Further citations from the Enneads will omit the title. ↩

5. IV,8,1. ↩

6. P. Henry. ‘The Place of Plotinus in the History of Thought’. In The Enneads. Third ed. Abridged, op. cit., xlii – lxxxiii. ↩

7. Compare the best-known ‘distinctions’ between the two philosophies – alternately, Plotinus’ division of reality into levels and his postulation of a One superior to the realm of Forms – with the sub-sections in Plato’s analogy of the Divided Line (Intelligence, Mathematical Reasoning, Belief and Illusion) Republic VI, 509d-511e, reflected in the hierarchy of both Plato’s ideal state and model of the soul, and ‘“The good therefore may be said to be the source not only of the intelligibility of the objects of knowledge, but also of their being and reality; yet it is not itself that reality, but is beyond it, and superior to it in dignity and power.”’ Republic VI, 509b. Further, ‘…on at least one occasion (Plato) lectured to a general audience. We are told by Aristoxenus, a pupil of Aristotle, that many in Plato’s audience were baffled and disappointed by a lecture in which he maintained that Good is one.’ The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy. Ed. R. Audi. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995, 623.) Panofsky, for example, accepted Plato at his word, confusing the reason of cognition with the non-discursive ‘reason’ of dualist contemplation, contributing to the maintenance of both a false distinction between Plato and Plotinus and a barrier to an understanding of their philosophies, of the relationship between them, and of their impact on Western culture. ‘Ultimately the theory of Ideas, originally a philosophy of human reason, was transformed almost into a logic of divine thought.’ E. Panofsky. Idea: A Concept in Art Theory. 1924. Reprint. Trans. J. Peake. New York: Harper and Row,1968, 38. Nietzsche made the same error, regarding Platonic dialectic as a development on Socratic rationalism (The Birth of Tragedy (1872) Section 13, in The Birth of Tragedy and The Case of Wagner. Trans. W. Kaufmann. New York: Vintage, 1967, 88-89). Similarly Deleuze, who, despite noting Bergson’s ‘obsession with the pure’ and that his method of intuition was Platonic in inspiration, distinguished between Bergson and Plato on the point of the latter’s dialectic (writing that Bergson considered Platonic dialectic to be valid only in the beginning of philosophy). G. Deleuze. Bergsonism. Trans. H. Tomlinson, B. Habberjam. New York, 1988, 22, 120. Again, Stern-Gillet: ‘He (Plotinus) locates selfhood in the soul, further specifying that the inner core of our being is that ‘part’ of the soul which is capable not only of discursive thinking directed at the forms immanent in this world, but also of the intuitive understanding of intelligible realities as such.’ S. Stern-Gillet. “Plotinus and His Portrait.” The British Journal of Aesthetics 37, 3 (July 1997): 211-225, 214. In the Timaeus, Plato distinguished between the ‘rational’ and the scientific. He equated dialectic with ‘pure thought’, ‘intelligence’, and the direct apprehension of truth. Republic VI, 511b. Plotinus regarded Platonic dialectic as ‘authentic science’ which he opposed to ‘seeming-knowledge (‘sense-knowledge’)’ I,3,4, and defined it as ‘the Method, or Discipline, that brings with it the power of pronouncing with final truth upon the nature and relation of things – what each is, how it differs from others, what common quality all have, to what Kind each belongs and in what rank each stands in its Kind and whether its Being is Real-Being, and how many beings there are, and how many non-Beings to be distinguished from Beings.’ I,3,4. He correctly believed that Platonic dialectic is concerned with ‘realities’ (the Forms) and not with ‘words’ (the logic of discursive reasoning). I,3,5. For Plotinus, the hypostasis of Intellect is the site of reason. Intellect makes Soul rational by giving it a copy of what it has. The rational soul is the true man, within. ↩

8. ‘The cultivation of Reason remained at the centre of the Platonic life-style, but non-intellectual elements were now incorporated into the life of the soul, as energising psychic forces on which Reason draws. On the other hand, it also complicated Reason’s struggle for purity. Both aspects of the divided-soul model emerge in the Phaedrus metaphor of the soul as a pair of winged horses, joined together in natural union with their charioteer. One horse is white, noble and easily guided; the other is a dark, crooked, lumbering animal, shag-eared and deaf, hardly yielding to whip and spur.’ G. Lloyd, The Man of Reason, ‘Male’ and ‘Female’ in Western Philosophy. London: Methuen, 1984, 20. In the Phaedrus, Socrates argues that conflicting desires enables the love of wisdom. ‘The later Plato…thus saw passionate love and desire as the beginning of the soul’s process of liberation through knowledge’. Ibid. 21. In the Symposium, ‘in Diotima’s version of the lover’s progress Reason does not simply shed the perturbations of passion but assimilates their energising force. Reason itself becomes a passionate faculty and a creative, productive one.’ Ibid. 22. As an example of the function of another non-discursive element, the Republic’s myth of Er exemplifies Plato’s belief in the truth-revealing power of imagination. ↩

9. Phaedrus 247d5ff. Here Plato was referring to the moral Forms. For Plotinus, righteousness is a beautiful ‘active actuality’, like a statue in intellect. ↩

10. ‘“On the other hand, to say that it pays to be just is to say that we ought to say and do all we can to strengthen the man within us…’”. Republic IX, 589a. On his ideal society Plato wrote ‘“Perhaps,” I said, “it is laid up as a pattern in heaven, where he who wishes can see it and found it in his own heart. But it doesn’t matter whether it exists or ever will exist”’. Republic IX, 592b. Plato believed that the Forms are sources of moral and (particularly from the perspective of my thesis) religious inspiration. ↩

11. See, for example: Plotinus. Enneads Trans. A.H. Armstrong. In seven volumes. London: William Heinemann, 1966-1988, vol. V, 25 ↩

12. Republic VII, 514-521. Plato argued that we should develop the motion of our (non-discursive) ‘thought’ as much as possible to reflect (restore to likeness with) the motion of the universe and of divine thought. ‘Among movements, the best is that we produce in ourselves of ourselves – for it is most nearly akin to the movement of thought and of the universe…’ Timaeus 47, 89, in Timaeus and Critias. Trans. D. Lee. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1977, 120, and ‘There is of course only one way to look after anything and that is to give it its proper food and motions. And the motions that are akin to the divine in us are the thoughts and revolutions of the universe. We should each therefore attend to these motions and by learning about the harmonious circuits of the universe repair the damage done at birth to the circuits in our head, and so restore understanding and what is understood to their original likeness to each other. When that is done we shall have achieved the goal set us by the gods…’ 48, 90, ibid., 121-122. ↩

13. Armstrong described the often obscure Enneads as ‘an unsystematic presentation of a systematic philosophy’. Armstrong, op. cit., vol. I, xv ↩

Image