Bronze plaque of Hegel (1770-1831) by Karl Donndorf (1870-1941) emplaced in 1931 at Hegel-Haus in Stuttgart.

What Hegel read but never acknowledged and what all the academics missed. Why?

09.12.13

From Johann Gottlieb Buhle, Geschichte der neuern Philosophie seit der Epoche der Wiederherstellung der Wissenschaften, in six volumes, Johann Georg Rosenbusch, Göttingen, 1800, volume 2

pp. 341-353 continued

The world is maximality contracted or made finite, and the diversity of things arises from the differing kinds and degrees of contraction of maximality.1 However, in order to understand the maximum in its relation to the world, we must first, as Nicholas expresses it, have purged our understanding of all concepts of circles and spheres. It will then be found that it is not the most perfect body, like the sphere; nor a plane figure, like the circle or triangle; nor a straight line; but is raised above all of these, as it is above everything that can be comprehended by the senses, the imagination and the reason with material attributes. The maximum is the simplest and most abstract understanding; it contains all things and one; the line is at once triangle, circle and sphere; oneness is trinity and conversely; accident is substance; the body is mind; motion is rest etc. But unless we realise that the oneness of God must necessarily be a trinity as well, we have not yet completely purged our understanding of concepts of mathematical figures. Nicholas demonstrates this by an example borrowed from human understanding. The oneness of human understanding is nothing else than that which understands, that which is understandable, and the act of understanding. If we wish to ascend from that which understands to the maximum (that which understands infinitely), without adding that this is at once also the highest understandable and the highest act of understanding, we will not have a correct concept of the greatest and most perfect oneness.2 Nicholas applies the concept of the trinity of the primal maximum to the world as well, which as an image of that maximum must also express a threeness. This threeness of the universe manifests itself (1) in the mere possibility thereof or the primal material, (2) in the form, and (3) in the world soul or world spirit, which inheres in all things as well as in the whole. The

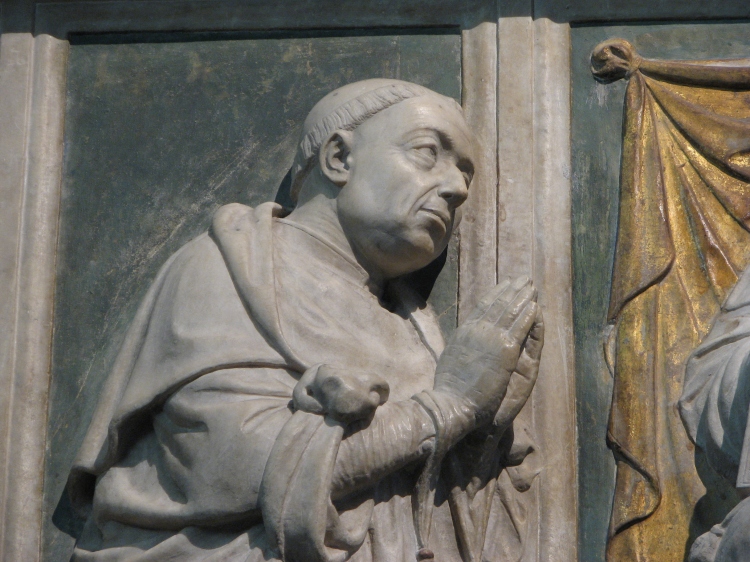

Nicholas of Cusa (1401-1464). From a painting by Meister des Marienlebens (Master of the Life of the Virgin), located in the hospital at Kues (Germany)

primal maximum also expresses the contracted maximum; creator and creation are one.3 Nicholas believed (missing words in German text – I am drawing attention to the fact that the German sentence is incomplete: its construction does not ‘add up’. The intended meaning is something like ‘N. believed one/he could find in the contracted maximum…the principal kinds of worldly creatures…’ Trans.) in the contracted maximum and its relation to the divine the principal kinds of worldly creatures, which differ in their degree of perfection, as Ficino had assumed. He too placed man on the intermediate level, as a link between the lower, lifeless organic and animal world on the one hand and the world of the angels and the divine on the other. But in these premises he also found—as Ficino had not—the explanation of the mystery of the incarnation of god as man. God wished to raise his work, the essence of creation, to perfection, and this could only be done by himself becoming a creature (created thing). As this creature he chose man, because man occupies the middle position in the order of worldly beings and is therefore the bond of his connection with the whole. God, who exists omnipresent in all things, assumed physical humanity and could do so without coming into contradiction with his own being; for considered absolutely, creator and creation are in any case one.4

Part three/to be continued…

Notes

1. Ibid. Book II, ch. 6. Vol. 1 fol. 16. ↩

2. Ibid. Book I, ch. 10. Oportet philosophiam, ad trinitatis notitiam ascendere volentem, circulos et spheras evomuisse. Ostensum est in prioribus unicum simplicissimum maximum; et quod ipsum tale non fit nec perfectissima figura corporalis, ut est sphera, aut superficialis, ut est circulus, aut rectilinealis, ut est triangulus, aut simplicis rectitudinis, ut est linea. Sed ipsum super omnia illa est. Itaque illa, quae aut per sensum, aut imaginationem aut rationem cum naturalibus appendiciis attinguntur, necessario evomere oportet, ut ad simplicissimam et abstractissimam intelligentiam perveniamus, ubi omnia sunt unum; ubi linea sit triangulus, circulus, et sphera; ubi unitas sit trinitas, et e converso; ubi accidens sit substantia; ubi corpus sit spiritus; motus fit quies et caetera huiusmodi. Et tunc intelligitur, quando quodlibet in ipso uno intelligitur unum, et ipsum unum omnia, Et per consequens quodlibet in ipso omnia. Et non recte evomuisti spheram, circulum, et huiusmodi, si non intelligis, ipsum unitatem maximam necessario esse trinam. Maxima enim nequaquam recte intelligi poterit, si non intelligatur trina. Ut exemplis at hoc utamur convenientibus: Videmus unitatem intellectus non aliud esse, quam Intelligens, Intelligibile et Intelligere. Si igitur ab eo, quod est Intelligens, velis te ad maximum transferre et dicere, maximum esse maxime Intelligens, et non adiicias, ipsum etiam esse maxime Intelligibile et maxime Intelligere; non recte de unitate maxima et perfectissima concipis. (Philosophy, desiring to ascend unto a knowledge of this Trinity, must leave behind circles and spheres. In the preceding I have shown the sole and very simple Maximum. And I have shown that the following are not this Maximum: the most perfect corporeal figure (viz., the sphere), the most perfect surface figure (viz., the triangle), the most perfect figure of simple straightness (viz., the line). Rather, the Maximum itself is beyond all these things. Consequently, we must leave behind the things which, together with their material associations, are attained through the senses, through the imagination, or through reason—so that we may arrive at the most simple and most abstract understanding, where all things are one, where a line is a triangle, a circle, and a sphere, where oneness is threeness (and conversely) where accident is substances, where body is mind, where motion is rest, and other such things. Now, there is understanding when (1) anything whatsoever in the One is understood to be the One, and the One (is understood to be) all things, and consequently, (2) anything whatsoever in the One (is understood to be) all things. And you have not rightly left behind the sphere, the circle, and the like, unless you understand that maximal Oneness is necessarily trine—since maximal Oneness cannot at all be rightly understood unless it is understood to be trine. To use examples suitable to the foregoing point: We see that oneness of understanding is not anything other than that which understands, that which is understandable, and the act of understanding. So suppose you want to transfer your reflection from that which understands to the Maximum and to say that the Maximum is, most greatly, that which understands; but suppose you do not add that the Maximum is also, most greatly, that which is understandable, together with being the greatest actual understanding. In that case, you do not rightly conceive of the greatest and most perfect Oneness.) ↩

3. Ibid. Book II, chh. 7–10, Vol. 1, fol. 17–20 ↩

4. Ibid. Book III, ch. 2f. Vol. 1. fol. 25 ↩

English translations of the works of Cusanus by Jasper Hopkins