‘Ye shall know them by their fruits. Do men gather grapes of thorns, or figs of thistles?’

In The Genealogy of Morals Nietzsche sliced and diced priestly asceticism. In The Protestant Ethic and the “Spirit” of Capitalism Weber asserted that it is a ‘purely historical study’1 of the impact of Protestant asceticism. In his writing he argued for a resolute facing of the facts, yet the true attitudes of these two hard men towards ‘priest’ and ‘Protestant’, indicatively stated by them in those books is conveyed by Nietzsche’s ‘ascetic ideal’ and in Weber’s concept with double meanings of ‘innerworldly’, superficially distinct from the ‘otherworldly’ asceticism of monastic life. Despite the forceful and bitter rhetoric of Nietzsche and the more scholarly (until criticised, as in his rejoinders) tenor of Weber’s writing, their critiques of asceticism, built on its mystical essence, embody a defence of that essence and are calls for its centrality to modern life.

Nietzsche believed that the focus of asceticism – from the origins of Christianity through the Enlightenment to his time – and what has undermined Christianity – modern science – is the ‘ascetic ideal’ – ‘with its sublime moral cult, with its brilliant and irresponsible use of the emotions for holy purposes’.2 This ideal, expressed in different forms such as God or knowledge, is ‘truth’ – the goal of a deluded faith in reason. While asceticism can benefit the philosopher’s and scholar’s intellectual work, it is none the less excessively repressive, world and life-denying.

The ascetic ideal is held by the virtuoso of guilt the priest above the herd, his sick patients, as symbol and proof of their guilt. The ascetic ideal is an artifice for the preservation of life, because it gives meaning to what is otherwise without meaning. Yet although it is generated by the instinct of self-preservation, its banner is ‘triumph in agony’.3 Nietzsche wrote that the ascetic ideal is the greatest disaster in the history of European health. With the ‘death of God’ his bourgeois society was free – to live well, to be selfish, secure, passive and mediocre. He thought his society’s cultural condition was meaningless exhaustion – nihilist. But this same climate offered a potential for renewal for those with the strength and capacity to live without illusions.

Weber believed he had made a discovery in the relationship between Protestantism and capitalism that could be traced to Luther’s spiritual revolution – his liberation of everyman from the priest – to become his own ‘priest’, and his notion of a secular ‘calling’ (Beruf) which gave religious and moral dignity to activity in the world. Weber argued that Calvin developed on this, and the elements and asceticism of Calvinist doctrines (and their offshoots in other churches), particularly predestination with the possibility of grace through works or the sanction of damnation took priority in his argument.

Since the eternal fate of the believer was unknown and, fearing damnation, he should live as if he were one of the elect by enhancing God’s glory and enriching His world through work and enterprise. He should not do so for the sake of idle pleasure or greed – he should live as an ‘(inner)worldly ascetic’, channelling his disciplined and concentrated energy into economic activity. He should contain uninhibited emotion, avoiding erotic pleasure and the instinctive enjoyment of life. He should avoid displays of wealth. Living simply, rationally, with order and method, he should accumulate the profits from his enterprise and re-employ them, building on what he had created, thereby enhancing the possibility of his grace. Seeking salvation through immersion in his vocation, he imbues the world with religious significance. Economic success was a sign of God’s blessing. Not only did this success result in the accumulation of capital which became the engine for the growth of capitalism, more importantly for Weber was the development of a bourgeois economic ethic – the ‘spirit of capitalism’ – which developed from the ascetic rationalism of the early Protestants to the rationalisation of economic and political life today.

Under the burden of predestination and a severe ethics, ‘innerworldly’ asceticism and the ‘spirit of capitalism’ progressed together but by the late nineteenth century, as concern with salvation and Christianity itself had declined, and rationalisation had advanced in science, technology, bureaucracy and law, there was left a society suffused with a disciplined work-focused inner orientation suited to the nature of capitalism but without the religious foundation. People suffered disenchantment and a loss of freedom and meaning. What had been a ‘light cloak’ for the religious had become a ‘steel shell’ (stahlhartes Gehause) for the modern. To counter this, Weber argued that individuals should find a Beruf or ‘calling’ in a value sphere (art, science, politics, religion) and to practice that calling with ‘passionate devotion’. His focus became the heroic individual who might be a model for others, one whose fearless life echoed the same principled asceticism of the earlier Calvinists.

Numerous differences can be found between Nietzsche and Weber regarding their positions on the effects of asceticism – Christianity, which Nietzsche hated and regarded as a millennial catastrophe that had promoted the decadence of modern man but which, in Protestantism, Weber thought had given an ethical core to capitalism; Christian guilt, which Nietzsche saw as the priest’s means of crippling humanity but which, as it operated with the requirement of proof as a sanction through predestination, Weber thought was his great discovery to understanding the origins of the ‘spirit of capitalism’; science, which Nietzsche regarded as ultimately a delusion but which Weber was committed to and democracy which, echoing equality before God was for Nietzsche another execrable continuation of ascetic Christianity but which Weber believed was necessary for a society’s health. Where Nietzsche hated modernity and the reduction of life to quantitative measures, Weber argued that modernity had liberating potential and that Protestant asceticism was fundamental to the efficiencies of rationalised modern life.

But the differences begin to blur on closer inspection: the approaches by both Nietzsche and Weber to asceticism (despite Weber’s assertion to the contrary) are psychological. Weber believed that rationalisation together with bureaucratisation had resulted in ‘warring’ autonomous spheres of activity in which people worked as functionaries, disenchanted and deprived of meaning and freedom. He also thought that the conditions that had sustained liberal democracy had been undercut by modernity and came to focus his hopes on plebiscitary democracy and charismatic leadership as a counter to rationalisation and bureaucratisation.

Nietzsche’s propensity for the most freewheeling hypocrisy is well exemplified by ‘I have great respect for the ascetic ideal so long as it really believes in itself and is not merely a masquerade.’4 And this is the point with both Nietzsche and Weber – it is necessary to push through their words, through their surface arguments, to their deeper purpose – one which arose among intellectuals in response to the increasing pressure on belief in God and its overt acknowledgement by the rise of science, by the rise of our objective knowledge of the world that Nietzsche was in turn so critical of and denied and that Weber expressed commitment to – the defence of Neoplatonic mysticism – the major mystical current in the West, which suffuses philosophy, which philosophers are so afraid to address for fear of what doing so will expose in the achievements of ‘rigorous philosophic reason’, and the influence of which is throughout our culture.5

From the Dionysiac ineffability in The Birth of Tragedy to the final synoptic ‘aphorism’ in The Will to Power, Nietzsche was a post-Christian Neoplatonist. Why is this not commonly stated? No modern philosopher has been more committed to the ‘ascetic ideal’, to a life of religious asceticism than Nietzsche. His rage and bitterness are those of a man who had been conditioned in Christianity, who understood and hated its hostility to life but who, unable to release its ideal, knew his time had passed. With God in heaven now dead, the stage was cleared for his appearance on earth in Nietzsche’s response to late nineteenth century capitalism – Dionysus as the overman.

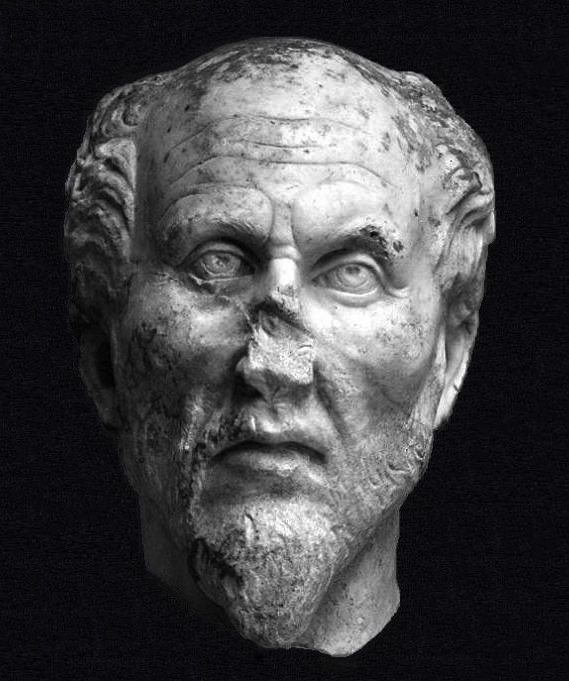

And this overman, this sculptor and perfecter of self, this rejecter of the (modern) world can be traced to Plotinus’ resonant sculptor around whom The Enneads are written. Weber shared Nietzsche’s romantic mourning.6 His solution to ‘the crisis of modernity’, within modernity – the exemplary individual devoted to his Beruf – a solution more scholarly, more sociable through service, less aggressive in depiction, less colourful and bilious, (his success in life – compared with Nietzsche’s failures – no doubt bore on this) drew on Nietzsche’s writing and the Neoplatonic tradition.

Weber’s use of Beruf derives from Luther7 whose believer, seeking unio mystica with God practised his calling in the world, thereby giving his worldly activity a religious significance. Weber’s exemplary individual, in a world where meaning had been destroyed by rationalisation and the loss of an over-riding salvific religious belief, with equal devotional self-sacrifice, seeks to re-establish harmonious meaning within himself. In so doing, he ‘rationally’ shapes himself.8 As with the subscriber to Nietzsche’s ascetic ideal, he ‘subordinates “mere” life to a value or purpose “out-side” and above life as it is. (He) interprets and values life as a bridge to a higher form of existence’9

With his hair-splitting concept of ‘innerworldly’ asceticism, Weber emphasised the ‘hard’, rational and ethical asceticism practised in the world by Calvinists and distinguished it from the ‘otherworldly’ asceticism of the contemplative Catholic. Yet he wrote ‘It is evident that mystical contemplation and rational asceticism in the calling are not mutually exclusive (Weber’s emphasis).’10 Weber’s blending of Lutheranism and Calvinism in his concept of ‘innerworldly’ asceticism is most interesting. According to Weber, in both Lutheranism and Calvinism faith must be proven in its effects, but the former enables union with God in this world, the latter is oriented to that with God in the next. Where Weber concentrated in The Protestant Ethic on the influence of Calvinism, the mystical element in Lutheranism sustains his argument in that book and in his other thought on these matters. It is as if the body of Calvinism conveys the spirit of Lutheranism.11

Weber indicates his heritage and summarises his underlying argument in the following words from The Protestant Ethic: ‘Christian asceticism, which was originally a flight from the world into solitude, had already once dominated the world on behalf of the Church from the monastery, by renouncing the world. In doing this, however, it had, on the whole, left the natural, spontaneous character of secular everyday life unaffected. Now it would enter the market place of life, slamming the doors of the monastery behind it, and set about permeating precisely this secular everyday life with its methodical approach, turning it toward a rational life in the world, but neither of this world nor for it.’12

The ‘flight from the world into solitude’ are the concluding words of The Enneads.13 The wish of both Weber and Nietzsche was that the ascetic who was no longer, could be no longer Christian, an overt believer in God, now with his religious beliefs concealed, as a subscriber to the ‘ineffable’, would leave the monastery of faith and enter the Nietzschean marketplace of modernity and live ‘God in heaven is dead, but creates on earth as me’. Nietzsche’s version as Dionysiac overman, as true Redeemer,14 was more deeply romantic, Weber’s man of the Beruf more consonant with modernity, less noisily integrating mysticism with capitalism – methodical and rationalising. Both figures were to heal the ‘dissolution of spiritual unity’15 in late nineteenth century capitalist society. Nietzsche damned religion and pointed the way forward through mysticism. Weber advocated mysticism but allowed that the embrace of religion was there for those not up to his mystical challenge.

Nietzsche’s overman and Weber’s man of the ‘calling’ have a common heritage in Plotinus’ sculptor. While, of the three, Weber’s model is most comfortable within his society, even there Weber had built a wall between the everyday and the value-spheres. His proscription of the mixing of the calling with ‘everyday’ life, as if the latter were something less than, is evidence of the striving for transcendent spiritual purity which is in all three models. All three face away from this world. The story of the impact of Neoplatonism on our culture is the great hidden, little explored and told story.

Notes

1. Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the “Spirit” of Capitalism and Other Writings, trans. Peter Baehr and Gordon Wells, Penguin 2002, 121 ↩

2. Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy and The Genealogy of Morals, trans. Francis Golffing, Doubleday, New York, 1956, 280 ↩

3. Ibid., 254 ↩

4. F. Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy and The Genealogy of Morals, op. cit., 294 These words, amongst his railing against ‘rotten armchairs’, ‘prurient eunuchdom’ and ‘coquettish dung beetles’, not to mention the basis of his argument through the entire text of The Genealogy of Morals and other writing, are at the end of The Genealogy of Morals. ↩

5. William Franke’s groundbreaking two volume anthology On What Cannot Be Said, University of Notre Dame Press, Indiana, 2007 traces the history of apophaticism in the West through the writing of its greats in philosophy, religion, literature and the arts. Mark Cheetham has written on its impact in the visual arts. M. Cheetham, The Rhetoric of Purity, Essentialist Theory and the Advent of Abstract Painting, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1991. ↩

6. In Nietzschean language he wrote ‘In (the Puritan) Baxter’s view, concern for outward possessions should sit lightly on the shoulders of his saints “like a thin cloak which can be thrown off at any time.” But fate decreed that the cloak should become a shell as hard as steel. As asceticism began to change the world and endeavoured to exercise its influence over it, the outward goods of this world gained increasing and finally inescapable power over men, as never before in history. Today its spirit has fled from this shell – whether for all time, who knows? … No one yet knows who will live in that shell in the future. Perhaps new prophets will emerge, or powerful old ideas and ideals will be reborn at the end of this monstrous development. Or perhaps … it might truly be said of the “last men” in this cultural development: “specialists without spirit, hedonists without a heart, these nonentities imagine they have attained a stage of humankind never before reached.”’ The Protestant Ethic and the “Spirit” of Capitalism and Other Writings, op. cit., 121 ↩

7. ‘the German mystics did a great deal of preparatory work on the idea of the calling in the Lutheran sense.’ The Protestant Ethic and the “Spirit” of Capitalism and Other Writings, op. cit., 32 ↩

8. ‘The ascetic style of life … meant a rational shaping of one’s whole existence in obedience to God’s will.’ Ibid., 104 ↩

9. Harvey Goldman, Politics, Death, and the Devil, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1992, 264 ↩

10. The Protestant Ethic and the “Spirit” of Capitalism and Other Writings, op. cit., 141 ↩

11. The impact of Lutheranism and its ministers in his family on Nietzsche is well known. ↩

12. Ibid., 104-105 ↩

13. ‘This is the life of gods and of the godlike and blessed among men, liberation from the alien that besets us here, a life taking no pleasure in the things of earth, the passing of solitary to solitary.’ Plotinus, The Enneads trans. Stephen MacKenna, Penguin, London, 1991, VI 9, 549. Armstrong translated this as the ‘flight of the alone to the Alone’ Plotinus Enneads trans. A.H. Armstrong, William Heinemann, London, 1966-1988. vol. VII, 345. In Thus Spoke Zarathustra Nietzsche wrote ‘Thus they came to a cross-road: there Zarathustra told them that from then on he wanted to go alone: for he was a friend of going alone.’ F. Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra – A Book for Everyone and No One, trans. R.J. Hollingdale, Penguin, 2003, 99-100 ↩

14. The Birth of Tragedy and The Genealogy of Morals, op. cit., 229. Weber’s figure was no less self-redemptive. ↩

15. ‘In the present, where we operate so much with the concept of “life,” “experience,” etc., as a specific value, the inner dissolution of that unity, the contempt for the “man of the calling” (cf. ‘the man of the cloth’) is tangible.’ The Protestant Ethic and the “Spirit” of Capitalism and Other Writings, op. cit., 313 ↩

Image