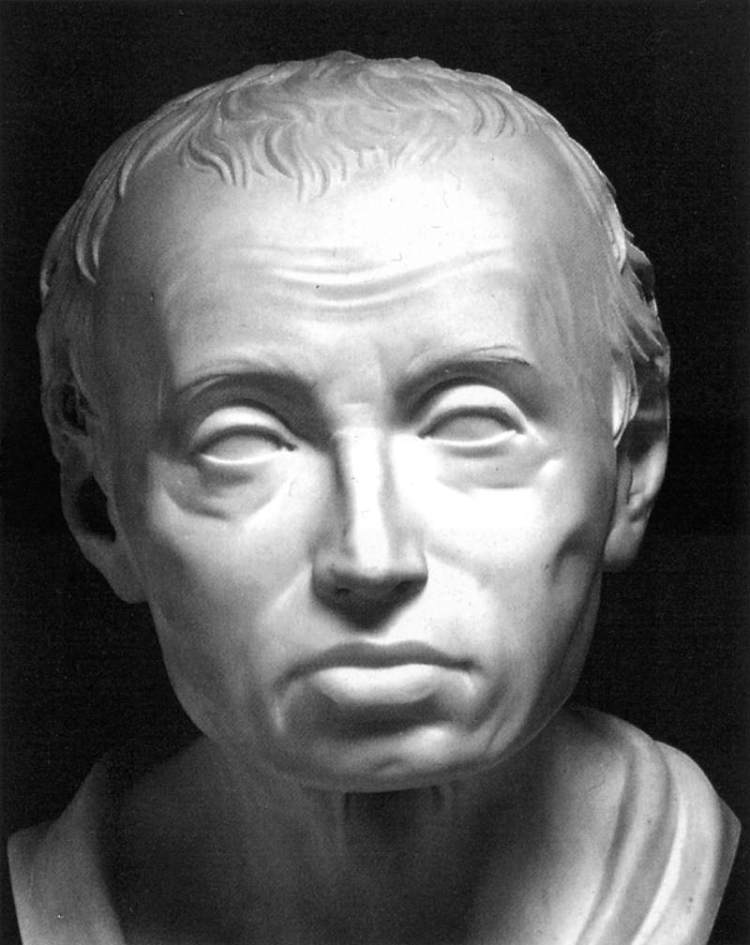

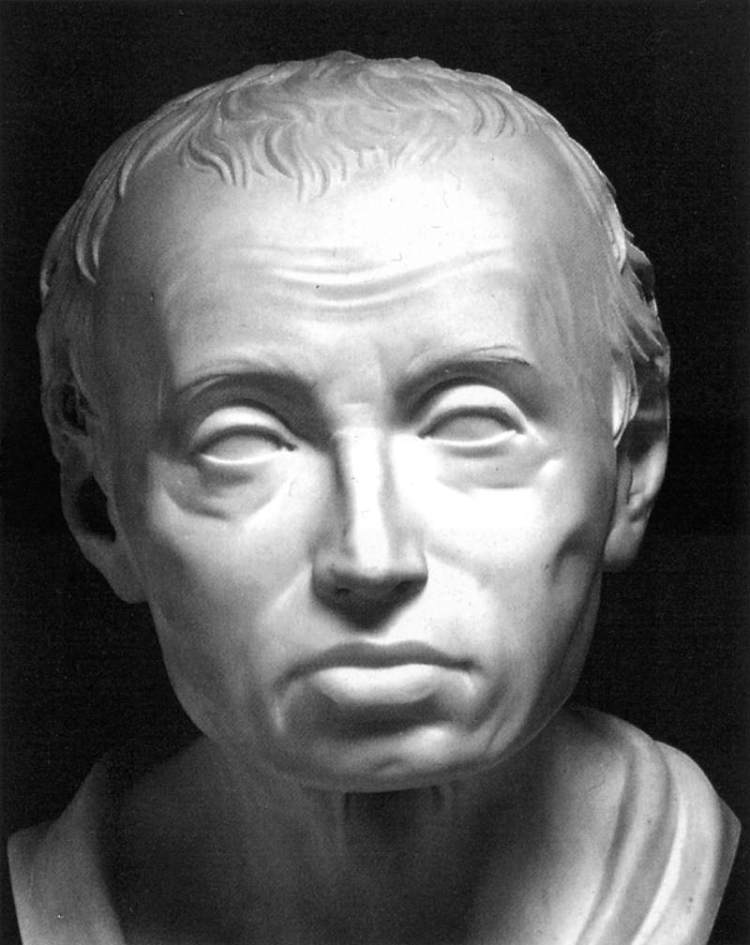

Immanuel Kant by Karl Friedrich Hagemann, 1801, marble, Kunsthalle, Hamburg

How to retain the primacy of consciousness over matter: attach a carefully worded lie to the greatest scientific hypothesis – thus Kant’s ‘Copernican turn’

Kant wrote: ‘…the fundamental laws of the motions of the heavenly bodies gave established certainty to what Copernicus had at first assumed only as an hypothesis, and at the same time yielded proof of the invisible force (the Newtonian attraction) which holds the universe together. The latter would have remained for ever undiscovered if Copernicus had not dared, in a manner contradictory of the senses, but yet true, to seek the observed movements, not in the heavenly bodies, but in the spectator. The change in point of view, analogous to this hypothesis, which is expounded in the Critique, I put forward in this preface as an hypothesis only, in order to draw attention to the character of these first attempts at such a change, which are always hypothetical. But in the Critique itself it will be proved, apodeictically not hypothetically, from the nature of our representations of space and time and from the elementary concepts of the understanding.’ Immanuel Kant, Preface to the Second Edition, Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, Trans., Norman Kemp Smith, Macmillan, London, 1987, 25 (Footnote)

and ‘We must therefore make trial whether we may not have more success in the tasks of metaphysics, if we suppose that objects must conform to our knowledge. This would agree better with what is desired, namely, that it should be possible to have knowledge of objects a priori, determining something in regard to them prior to their being given. We should then be proceeding precisely on the lines of Copernicus’ primary hypothesis. Failing of satisfactory progress in explaining the movements of the heavenly bodies on the supposition that they all revolved round the spectator, he tried whether he might not have better success if he made the spectator to revolve and the stars to remain at rest. A similar experiment can be tried in metaphysics, as regards the intuition of objects. If intuition must conform to the constitution of the objects, I do not see how we could know anything of the latter a priori; but if the object (as object of the senses) must conform to the constitution of our faculty of intuition, I have no difficulty in conceiving such a possibility.’ (22)

Kant’s incorrect assertion that Copernicus had sought the observed movements in the spectator is not the crucial point – it is that Kant thereby had the pretext to give priority over matter to ‘mind’/consciousness – via concepts and the ‘forms of intuition’. Copernicus’ hypothesis is an objective hypothesis about the world, the functioning of which Copernicus recognised requires neither the spectator – nor their ‘mind’/consciousness.1

In On the Revolutions of Heavenly Spheres, Copernicus a couple of times referred to the spectator: ‘For every apparent change in place occurs on account of the movement either of the thing seen or of the spectator, or on account of the necessarily unequal movement of both. For no movement is perceptible relatively to things moved equally in the same directions – I mean relatively to the thing seen and the spectator.’ Nicolaus Copernicus, On the Revolutions of Heavenly Spheres, Ed., Stephen Hawking, Running Press, Philadelphia, 2002, 12

But the spectator did not figure in his hypothesis itself: ‘For the daily revolution appears to carry the whole universe along, with the exception of the Earth (my emphasis) and the things around it. And if you admit that the heavens possess none of this movement but that the Earth (my emphasis) turns from west to east, you will find – if you make a serious examination – that as regards the apparent rising and setting of the sun, moon, and stars the case is so. And since it is the heavens which contain and embrace all things as the place common to the universe, it will not be clear at once why movement should not be assigned to the contained rather than to the container, to the thing placed rather than to the thing providing the place.’ (12-13)

Not only – going beyond Kant’s noumenal barrier (and, most significantly, towards acquisition of knowledge of the world) – was careful observation crucial to Copernicus’ hypothesis: ‘Having recorded three positions of the planet Jupiter and evaluated them in this way, we shall set up three others in their place, which we observed with greatest care at the solar oppositions of Jupiter’ (291), not only was he entirely comfortable with appearances, repeatedly referring to them and setting out the means for counteracting them: ‘For in order to perceive this by sense with the help of artificial instruments, by means of which the job can be done best, it is necessary to have a wooden square prepared, or preferably a square made from some other more solid material, from stone or metal; for the wood might not stay in the same condition on account of some alteration in the atmosphere and might mislead the observer’ (61), he dealt with the reciprocal relationships between sun, earth and moon, irrespective of which body was moving: ‘It is of no importance if we take up in an opposite fashion what others have demonstrated by means of a motionless earth and a giddy world and race with them toward the same goal, since things related reciprocally happen to be inversely in harmony with one another’ (60), even writing ‘And for this reason we can call the former movement of the sun – to use the common expression – the regular and simple movement’ (161).

The Sage of Königsberg steps forth: ‘it is clearly shown, that if I remove the thinking subject the whole corporeal world must at once vanish: it is nothing save an appearance in the sensibility of our subject and a mode of its representations’ (Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, op. cit., 354).

Sapere aude…

Note

1. Bertrand Russell wrote that Kant should have ‘spoken of a “Ptolemaic counter-revolution (my italics)”, since he put man back at the centre from which Copernicus had dethroned him..’ Bertrand Russell, Human Knowledge, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1948, 9, in Paul Redding, Hegel’s Hermeneutics, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 1996, 3. Kant’s calculated nonsense was replicated by A.C.Ewing ‘“Just as Copernicus taught that the movement round the earth which men had ascribed to the sun was only an appearance due to our own movement,” stated Ewing, “so Kant taught that space and time which men had ascribed to reality were only appearances due to ourselves. The parallel is correct.”’ Ibid. Space is the objective distribution of matter, time (not the measure of time) is the objective movement of matter in space. Space, time, matter and motion (all objective) are inseparable. Kant’s crucial spectator with their consciousness is the product of these. ↩