Movement and rest in ‘thought’, the most intense activity and stillness in unity

The hypostases are interconnected, with Body having its existence in Soul, Soul its source in Intellect1 and Intellect its generation from the One. At the same time the One has independence from Intellect as Intellect in turn has from Soul. The notion of illumination passes through the Enneads. The One lights Intellect which in turn illuminates Soul which gives light to this universe. The further away from the One, the weaker the illumination.

The double movement in Plotinus’ doctrine – from unity to increasing multiplicity and return to unification and unity concerns an eternal outpouring from a transcendent One, descending through levels to the lowest reality – the universe of matter and the senses. With the purpose of showing the way to God, it is also an urging of soul through purification2 and simplification to ascend from a meditation on this universe to the one of intelligible reality, to union with the Good, which alone can give Soul true satisfaction. The impetus for the ascent is the memory of a beauty infinitely greater than its weak presence in this world.

Plotinus believed we have forgotten our true nature, which lies within us. So this ‘ascent of the mind to God’, fuelled by desire and remembrance, is equally a journey within, to the core of our being. The One is like the centre of concentric circles. It is beyond thought and desire, and therefore beyond movement. Intellect, which is thought and desire, both moves around the One, and is at contemplative rest. Soul, moved by aspiration towards and desire for Intellect, revolves around it.3

Progress of the soul in freeing itself from illusion and moving towards its goal, beyond the Platonic world of Forms, requires enormous moral and spiritual striving, of which few are capable4 and signifies a deepening contemplation, a closer communion between soul and its origin in pure reality.5 Plotinus’ philosophy unites the religious and the philosophical. Armstrong wrote that it amounts to a prayer.6

The perfect One, without movement, eternally creates and actuates its image, Intellect. Number gives Intellect – the eternal living reality and perfect unity-in-multiplicity – its structure. It in turn produces its image and activity, Soul. Nature is the lower phase and image of Soul, which, as its rational forming principle, carries form to matter.7 Though aspiring to Intellect in a ceaseless contemplation and therefore productive, it is almost the lowest form of contemplation, producing weak and dreamy forms, below which is only matter:

‘What does this mean? That what is called nature is a soul, the offspring of a prior soul with a stronger life; that it quietly holds contemplation in itself, not directed upwards or even downwards, but at rest in what it is, in its own repose and a kind of self-perception, and in this consciousness and self-perception it sees what comes after it, as far as it can, and seeks no longer, but has accomplished a vision of splendour and delight.’8

Matter (which also exists in Intellect), receives the Forms in the three-dimensional space of this universe. Though often referred to in the Enneads as ‘evil’, it has a weak tendency towards the One and so shares in its superabundant productivity.

Activity in the divine is reflected in the activity of the material universe. Existence at every level tends through quickening aspiration to rejoin the level above, of which it is a product and image. Contemplation of the source of an hypostasis always precedes and generates activity and production:

‘The procession of Intellect from the One is necessary and eternal, as are also the procession of Soul from Intellect and the forming and ordering of the material universe by Soul. This emanation from the One is because everything perfect is creative and produces something else. Here we touch an element in Plotinus’s thought which is of great importance, the emphasis on life, on the dynamic, vital character of spiritual being. Perfection for him is not merely static. It is a fullness of living and productive power. The One for him is Life and Power, an infinite spring of power, an unbounded life, and therefore necessarily productive.’9

Plotinus’ philosophy concerns one vast living system, streaming from the One: 10

‘…as the (Divine) plan holds, life is poured copiously throughout a Universe, engendering the universal things and weaving variety into their being, never at rest from producing an endless sequence of comeliness and shapeliness, a living pastime.’11

Life is an activity and power which is omnipresent, ever fresh, inexhaustible, ‘brimming over with its own vitality’,12 unquantifiable and indivisible – what is in the whole is in the part. The greater the living movement, the greater the beauty, and the more the embodied Good, which wakes and raises up the souls of those who respond to it. Hence the more intense is Soul’s desire for the source of that life, for the unity which overcomes loneliness and spiritual incompleteness: 13

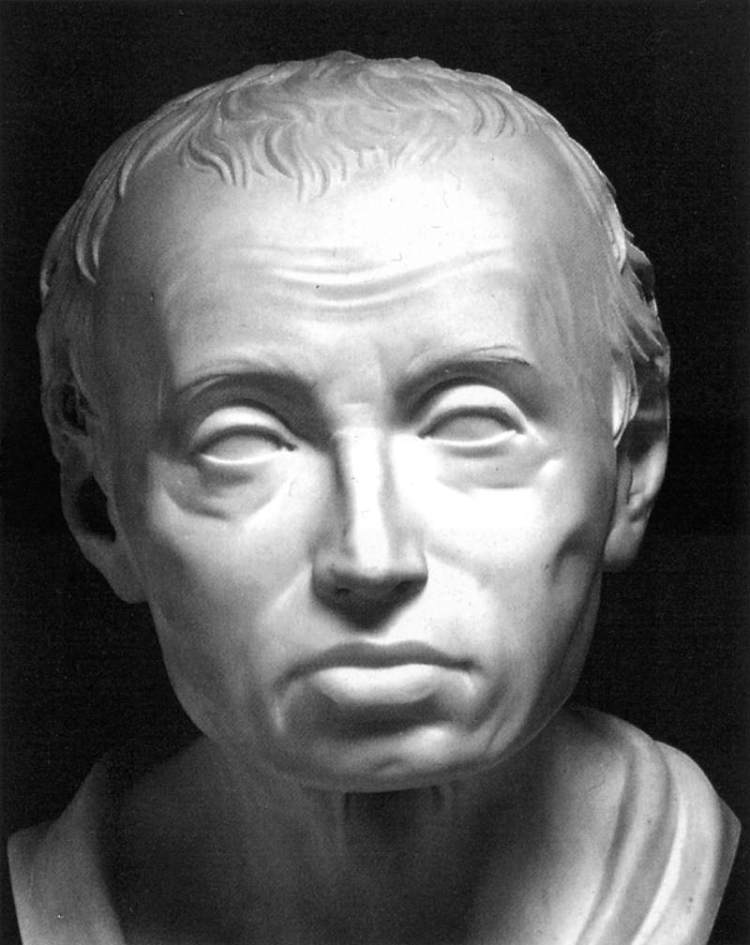

‘So here below also beauty is what illuminates good proportions rather than the good proportions themselves, and this is what is loveable. For why is there more light of beauty on a living face, but only a trace of it on a dead one, even if its flesh and its proportions are not yet wasted away? And are not the more life-like statues the more beautiful ones, even if the others are better proportioned? And is not an uglier living man more beautiful than the beautiful man in a statue? Yes, because the living is more desirable; and this is because it has soul; and this is because it has more the form of good; and this means that it is somehow coloured by the light of the Good, and being so coloured wakes and rises up and lifts up that which belongs to it, and as far as it can makes it good and wakes it.’14

Life for Plotinus is eternal creativity and creation, ultimately that of self.15 He several times used the metaphor of a tree to illustrate the process:

‘For the gathering together of all things into one is the principle, in which all are together and all make a whole. And individual things proceed from this principle while it remains within; they come from it as from a single root which remains static in itself, but they flower out into a divided multiplicity, each one bearing an image of that higher reality, but when they reach this lower world one comes to be in one place and one in another, and some are close to the root and others advance farther and split up to the point of becoming, so to speak, branches and twigs and fruits and leaves; and those that are closer to the root remain for ever…’16

Part two/to be continued…

Notes

1. Both Intellect and Soul are Forms. ↩

2. Plotinus distinguished between ‘civic’ and ‘purificatory’ virtues. The former pertain to life in this world, the latter to those which lead the Soul to ‘another life, that of the Gods’ and in Intellect. I,2.7. ↩

3. ‘All things are around the King of all, and That is the cause of all good and beautiful things, and all things belong to That, and the second things are around the Second and the third around the Third.’ I,7.2. This is one of the foundation-texts of Neoplatonic theology and is quoted from the questionably authentic Second Letter of Plato (312e1-4). In the Timaeus circles are the governing force in the universe and in our heads. Also ‘…if one ranks the Good as a centre one would rank Intellect as an unmoved circle and Soul as a moving circle; but moving by aspiration.’ IV,4.16. ↩

4. ‘…to those of power to reach, it is present; to the inapt, absent.’ VI,9.7. Cf. Bergson’s identification of two moral and spiritual types and his comparison between ‘static religion’ and ‘dynamic religion’ in ‘The Two Sources of Morality and Religion’, 1932. ↩

5. Soul arrives at Intellect by contemplation but Intellect arrives at the Good through immediate unity with it. ↩

6. Ibid, Vol.5, 29. ‘What is new (in Plotinus’ system)…is the notion of making the ‘Ideas’ states of being of the Intellect and no longer distinct objects, of bringing the very subject of thought into the intelligible world, of considering the hypostases less as entities than as spiritual attitudes.’ Henry op. cit., li. ↩

7. Here I use Armstrong’s terminology. MacKenna translated this as ‘Lower Soul’, ‘Nature-Looking and Generative Soul’, ‘Logos of the Universe’ and ‘ Reason-Principle of the Universe’. ↩

8. III,8.4. Also ‘the Nature best and most to be loved may be found there only where there is no least touch of Form.’ VI,7.33. ↩

9. Armstrong, op. cit., vol. I, xviii-xix. ↩

10. ‘…Life streaming from Life; for energy runs through the Universe and there is no extremity at which it dwindles out…’ III,8.5. ‘…the law is, “some life after the Primal Life, a second where there is a first; all linked in one unbroken chain; all eternal; divergent types being engendered only in the sense of being secondary”.’ II,9.3. ↩

11. III,2.15. ↩

12. VI,5.12. The vital power of Romanticism, traceable to Plotinus’ doctrine, does not imitate nature, it is the hand of nature. Thus the artwork is not at third remove from the Idea, rather, it carries the viewer ‘upwards’ and ‘inwards’ to it. See Kant’s Critique of Judgement (1790) Bk II, Analytic of the Sublime, No. 46 (Fine art is the art of genius) ‘Since talent, as an innate productive faculty of the artist, belongs itself to nature, we may put it this way: Genius is the innate mental aptitude (ingenium) through which nature gives the rule to art.’ The Sturm und Drang movement in Germany between 1770 and 1790 (with parallels in England and France) was the earliest expression of Romanticism and had vitalism as its nucleus. ↩

13. ‘Here is living, the true; that of today, all living apart from Him, is but a shadow, a mimicry.’ VI,9.9. Although the Cubists’ use of (developments on) the philosophies of Plato and Plotinus was certainly influenced by the ‘alienating’ effects of rapid technological developments at the turn of the century, Panofsky positioned this in a deeper, historical context, arguing that doubt and the turn to speculative thought (questioning the relationship between reality, senses, ‘mind’ and artistic production) dates from Mannerism. ‘…the Mannerists considered it obvious that this “idea” or concetto could by no means be purely subjective or “psychological”; and the question arose, for the first time, how it was at all possible for the mind to form a notion of this kind – a notion that cannot simply be obtained from nature, yet must not originate in man alone. This question led eventually to the question of the possibility of artistic production as such…precisely such a way of thinking was bound to realise that that which in the past had seemed unquestionable was thoroughly problematical: the relationship of the mind to reality as perceived by the senses…Before the eyes of art theorists there opened an abyss hidden until then, and they felt the need to close it by means of philosophical speculation…Earlier art theory (pre- mid-sixteenth century) had tried to lay the practical foundations for artistic production; now it had to face the task of proving its theoretical legitimacy. Thought now took refuge, so to speak, in a metaphysics meant to justify the artist in claiming for his inner notions a suprasubjective validity as to both correctness and beauty.’ Panofsky, op. cit., 82-83. Also ‘At odds with nature the human mind fled to God in that mood at once triumphant and insecure…’, ibid., 99. More broadly (or perhaps more profoundly) – ‘the opposition between “idealism” and “naturalism” that ruled the philosophy of art until the end of the nineteenth century and under multifarious disguises – Expressionism and Impressionism, Abstraction and Empathy – retained its place in the twentieth, must in the final analysis appear as a “dialectical antinomy.”…To recognise the diversity of these solutions and to understand their historical presuppositions is worthwhile for history’s sake, even though philosophy has come to realise that the problem underlying them is by its very nature insoluble.’ Ibid., 126. ↩

14. VI,7.22. ‘Why are the most living portraits the most beautiful, even though the other happen to be more symmetric? Why is the living ugly more attractive than the sculptured handsome? It is that the one is more nearly what we are looking for, and this because there is soul there, because there is more of the Idea of The Good…and this illumination awakens and lifts the soul and all that goes with it, so that the whole man is won over to goodness and in the fullest measure stirred to life.’ VI,7.22. Plato also tied life to truth. On the superiority of speech to writing – Socrates: ‘I mean the kind that is written on the soul of the hearer together with understanding…’ Phaedrus replied: ‘You mean the living and animate speech of a man with knowledge, of which written speech might fairly be called a kind of shadow.’ Phaedrus 276. ↩

15. ‘If there had been a moment from which He began to be, it would be possible to assert his self-making in the literal sense; but since what He is He is from before eternity, his self-making is to be understood as simultaneous with Himself; the being is one and the same with the making, the eternal ‘bringing into existence’.’ VI.8,20. Also ‘Is that enough? Can we end the discussion by saying this? No, my soul is still in even stronger labour. Perhaps she is now at the point when she must bring forth, having reached the fullness of her birth-pangs in her eager longing for the One.’ V.3,17. ↩

16. III,3.7. Also ‘The Supreme is the Term of all; it is like the principle and ground of some vast tree of rational life; itself unchanging, it gives reasoned being to the growth into which it enters.’ VI,8.15, and IV,4.11. In Creative Evolution, Bergson wrote ‘…life is tendency, and the essence of a tendency is to develop in the form of a sheaf, creating, by its very growth, divergent directions among which its impetus is divided.’ In H. Larrabee, ed. Selections from Bergson. New York, 1949, 72. Also compare Plotinus – ‘The fact that the product contains diversity and difference does not warrant the notion that the producer must be subject to corresponding variations. On the contrary, the more varied the product, the more certain the unchanging identity of the producer: even in the single animal the events produced by Nature are many and not simultaneous; there are the age periods, the developments at fixed epochs – horns, beard, maturing breasts, the acme of life, procreation – but the principles which initially determined the nature of the being are not thereby annulled…this is the unalterable wisdom of the Cosmos…’ IV.4,11 with Bergson ‘The animal takes its stand on the plant, man bestrides animality, and the whole of humanity, in space and time, is one immense army galloping beside and before and behind each of us in an overwhelming charge able to beat down every resistance and clear the most formidable obstacles, perhaps even death.’ From Creative Evolution in Selections from Bergson. op. cit., 105. ↩