The rose in the Rosicrucian cross is a concentration of mystical meanings including that of unfolding Mind. ‘To recognise reason as the rose in the cross of the present and thereby to enjoy the present, this is the rational insight which reconciles us to the actual…’ Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, Preface.

What Hegel read but never acknowledged and what all the academics missed. Why?

09.12.13

From Johann Gottlieb Buhle, Geschichte der neuern Philosophie seit der Epoche der Wiederherstellung der Wissenschaften, in six volumes, Johann Georg Rosenbusch, Göttingen, 1800, volume 2

pp. 341-353 continued

Nicholas of Cusa’s system is once again a pantheism which was at the same time intended as a theism, and thereby destroys itself. It betrays a bizarre mixture of mathematical and logical concepts. The divinity to Nicholas, as to Ficino, was really the logical concept of the highest order, conceived through the mathematical concept of the absolute (not relative) maximum, which precisely because it excluded all plurality therefore coincided with the concept of the absolute minimum, the absolutely simple and, insofar as it must include the highest being, absolute perfection; yet it was no more and no less than a purely logical concept, to which nothing objective corresponded. Hence the concern that Nicholas expresses that we may not understand his concept of the maximum in sufficiently pure and abstract terms; hence too his advice first to purge ourselves of all circles and spheres, that is, of all material attributes. He must surely have suspected that notwithstanding all his purges, the understanding yet cannot conceive the maximum bereft of material attributes as something real, for without them the concept dissolves into nothingness. But for Nicholas this suspicion did not really crystallize in a clear form. As long as he expresses his concept of God and his identity with the world in mathematical terms, his theology sounds even more pantheistic than Ficino’s; in essence, his and Ficino’s system are the same, as one can see from the relation in which he places God to the world—an equally theistical one. Thus the same errors underlie his system and Ficino’s.

Nicholas’ ideas as presented here also dominate the other works mentioned above. Some clarifications of them can be found in the Apologia doctae ignorantiae discipuli ad discipulum (Defence of learned ignorance by a student to a student), appended to Nicholas’ De docta ignorantia (On learned ignorance).1 It is addressed by a student of Nicholas to a fellow-student, against a work published by Wenck under the title Ignota literatura (Unknown learning), which argued with great passion against the nature of Nicholas’ conceptions. We may regard it as a production of Nicholas himself, as the author merely relates to his fellow-student Nicholas’ reaction to Ignota literatura and his judgements on the objections it contains. Possibly it is in fact Nicholas’ work, in which case it is the form in which he chose to defend himself.

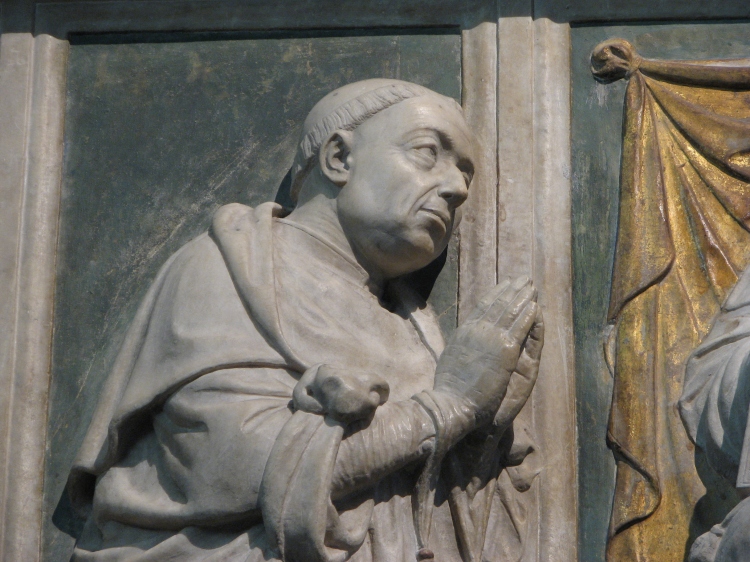

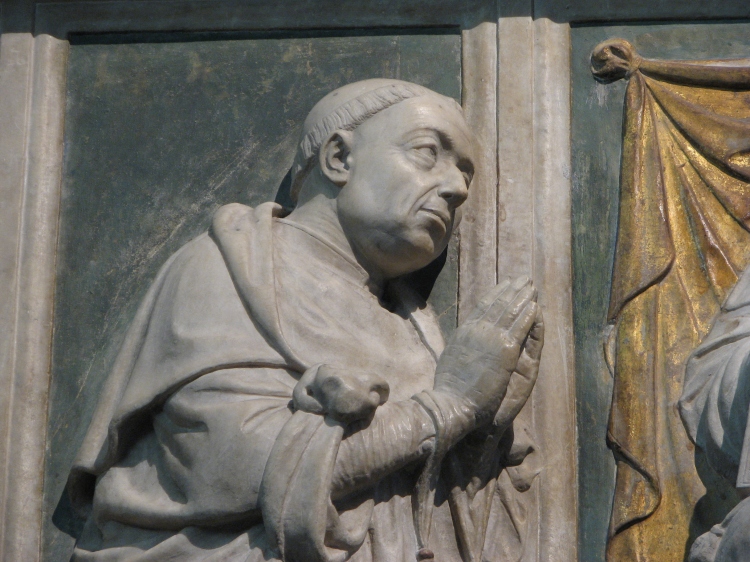

Nicholas of Cusa (1401-1464), detail of relief ‘Cardinal Nicholas before St. Peter’ on his tomb by Andrea Bregno, church of St. Peter in Chains, Rome

De coniecturis, in two books, is not, as one might expect, concerned with speculations or with probabilities and their bases, but contains a theory of the human cognitive faculty in general, considered from the viewpoint which Nicholas adopted, appropriate to his metaphysical system. Absolute truth is unattainable to man; praecisio veritatis inattingibilis, as Nicholas puts it; thus all human knowledge is merely probable, a speculation; and an investigation of the principle of speculation in the human mind is therefore an investigation of the cognitive faculty in general. Here too Nicholas’ philosophical language is the same mathematical–mystic language as in De docta ignorantia. In my opinion his idea of the human cognitive faculty can be best grasped from the following passage, which I quote here in his own words: Coniecturas a mente nostra, uti realis mundus a divina infinita ratione, prodire oportet. Dum enim humana mens, alta Dei similitudo, fecunditatem creatricis naturae ut potest participat, ex se ipsa, ut imagine omnipotentis formae, in realium entium similitudinem rationalia exerit. Coniecturalis itaque mundi humana mens forma existit, uti realis divina.—Ut autem mentem coniecturarum principium recipias, advertas oportet, quomodo ut primum omnium rerum atque nostrae mentis principium unitrinum ostensum est, ut multitudinis, inaequalitatis, atque divisionis rerum unum sit principium, a cuius unitate absoluta multitudo, ab aequalitate inaequalitas, et a connexione divisio effluat; ita mens nostra, quae non nisi intellectualem naturam creatricem concipit, se unitrinum facit principium rationalis suae fabricae. Sola enim ratio multitudinis, magnitudinis ac compositionis mensura est; ita ut ipsa sublata nihil horum subsistat. — Quapropter unitas mentis omnem in se complicat multitudinem; eiusque aequalitas omnem magnitudinem; sicut et connexio compositionem. Mens igitur unitrinum principium; primo ex vi complicativae unitatis multitudinem explicat; multitudo vero inaequalitatis atque magnitudinis generativa est. Quapropter in ipsa primordiali multitudine ut in primo exemplari magnitudines et perfectiones integritatum, et varias et inaequales, venatur; deinde ex utrisque ad compositionem progreditur. Est igitur mens nostra distinctivum, proportionativum, atque compositivum principium. — Rationalis fabricae naturale quoddam pullulans principium numerus est. Mente enim carentes, uti bruta, non numerant. Nec est aliud numerus, quam ratio explicata.2 (It must be the case that speculations originate from our minds, even as the real world originates from Infinite Divine Reason. For when, as best it can, the human mind [which is a lofty likeness of God] partakes of the fruitfulness of the Creating Nature, it produces from itself, qua image of the Omnipotent Form, rational entities, which are made in the likeness of real entities. Consequently, the human mind is the form of a speculated rational world, just as the Divine Mind is the Form of the real world. …In order that you may recognise that the mind is the beginning of speculations, take note of the following: just as the First Beginning of all things, including our minds, is shown to be triune (so that of the multitude, the inequality, and the division of things there is one Beginning, from whose Absolute Oneness multitude flows forth, from whose Absolute Equality inequality flows forth, and from whose Absolute Union division flows forth), so our mind (which conceives only an intellectual nature to be creative) makes itself to be a triune beginning of its own rational products. For only reason is the measure of multitude, of magnitude, and of composition. Thus, if reason is removed, none of these will remain. …Therefore, the mind’s oneness enfolds within itself all multitude, and its equality enfolds all magnitude, even as its union enfolds all composition. Therefore, mind, which is a triune beginning, first of all unfolds multitude from the power of its enfolding-oneness. But multitude begets inequality and magnitude. Therefore, in and through the primal multitude, as in and through a first exemplar-multitude, the mind seeks the diverse and unequal magnitudes, or perfections, of each thing as a whole; and thereafter it progresses to a combining of both multitude and magnitude. Therefore, our mind is a distinguishing, a proportioning, and a combining beginning. …Number is a certain natural, originated beginning that is of reason’s making; for those creatures that lack a mind, e.g. brute animals, do not number. Nor is number anything other than reason unfolded.) — We see here the reason why Nicholas chose to describe his philosophical system in mathematical terms: he found in numbers and numerical relations the principles of the cognitive faculty itself. It would take up too much space here to detail the manner in which he developed these principles. In doing so, too, Nicholas often loses himself so deeply in his mathematical mysticism that his theory, at least to me, becomes quite incomprehensible. However, anyone who wishes to study Nicholas’ system in its full internal detail and relations must regard De coniecturis as preparatory to it, even though Nicholas himself places it after his metaphysics and to some extent bases it on the latter.

Part four/to be continued…

Notes

1. Nic. Cus., Opera (Works), Vol. 1, p. 35 ↩

2. Nic. Cus. de coniect. Book I, ch. 3.4, Works Vol. I, fol. 42 ↩

English translations of the works of Cusanus by Jasper Hopkins