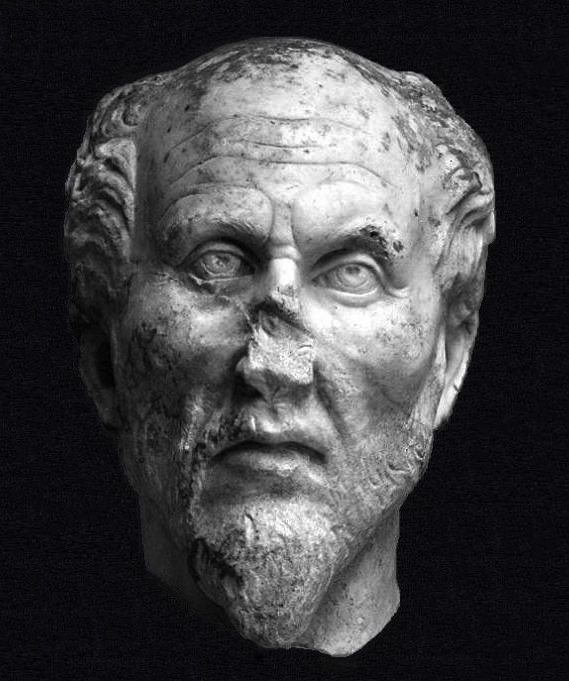

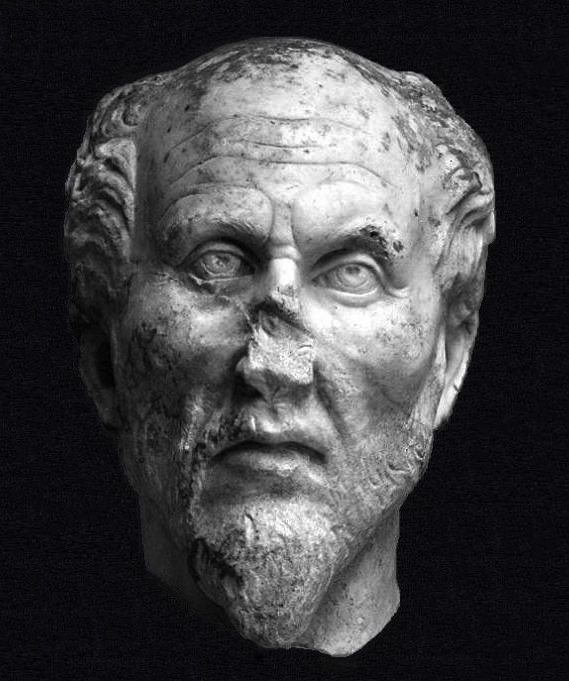

Plotinus (204/5-270), Anonymous, white marble, Ostiense Museum, Ostia Antica, Rome

Plotinus and the philosophical current he initiated continue to be denied the recognition they deserve by Western ideologues. As I wrote in my thesis ‘The heyday of those stages of capitalist ideology known as ‘Modernism’ and ‘post-modernism’ (equally aimed at undermining our trust in our senses and in our knowledge of the world through their engagement in praxis) have passed and the ideologues of the bourgeoisie have been forced, under the very pressure of change that produced Hegel and saw the absorption of his philosophy into materialism, now dialectical, to address mysticism. Hermeticism and other similar ‘esoteric’ belief systems offer them yet another way out – philosophy as myth, as account, as subjectivity, as sacred, ancient authority – philosophy still suffused with ‘God’, still focussing on consciousness, on what is secondary.’

Below I quote an excerpt from Paul S. MacDonald’s book Nature Loves to Hide – An Alternative History of Philosophy. His position is consistent with that of Magee, against whom I argued in my thesis – a defence of Western esotericism. But the text argues that the history of Western philosophy can be understood in ways very different from what is generally accepted.

***

Nature Loves to Hide – An Alternative History of Philosophy

Paul S. MacDonald

Alternative Books, 2018

1. The Alternative Tradition in Western Philosophy

In what way is this book an alternative history of philosophy, compared to an ordinary or standard history? For that matter, in what way can any account of something be an alternative to another account? One point to notice straight away is that this is not an alternate history of philosophy, since an alternate to x substitutes or replaces x by eliminating or cancelling x, whereas an alternative to x is another option for x, one which can coexist or stand along with it. For example, black and white squares alternate on a chessboard, whereas a backgammon board is (part of) an alternative game. Several candidates can stand for political office as alternatives, but once one of them is elected they are no longer alternatives; if the winner is disqualified for some reason then there may be an alternate who can take his or her place. Both words are derived from the same root word in Latin, alter (other), but alternative is mediately from alternativus, itself the participle of alternare, one thing after another, each thing taking turns. So, what about all the titles that would show up under the heading “History of (Western) Philosophy”? Frankly, at least within the last half-century, they are all alternate versions (for the most part) of the same story, each one displacing the others preceding it, nudging them towards the end of the shelf.

Every year, students of philosophy embark on the study of the history of their subject on a well-laid path, with well-marked high points. This “standard” history starts with Plato and Aristotle, then the Stoics, Epicureans, and other early adopters, then there’s a large blank, until the mainline reemerges in the Middle Ages with Albert the Great, Thomas Aquinas, and other middle thinkers, followed (maybe) by some Renaissance characters, and then hitting the highway in the Early Modern Period with Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, Hume, Locke, Berkeley, and Kant – the travellers are cruising now, things look more familiar, they recognise these names. From this point, the forward path diverges into more than one principal route, but, in any case, they’ve arrived where they expected when they started – the present. Every few years there are a few new books, in a major European language, on the history of western philosophy, especially “Modern Philosophy” or “The Enlightenment”, from Descartes to Kant or Nietzsche. Although they may address different topics or follow a variety of themes, these new books always feature the same main characters in the same sequence.

In contrast, an alternative history of western philosophy constitutes its own tradition and estate. Alongside philosophy, theology, and natural science, this history has its own principal figures, themes and texts, passed on from one generation to the next, often directly from teacher to pupil. It existed as a shadowy parallel or doppelganger, sometimes closer, sometimes farther from orthodox lines of thought, about God, about humans, and about the natural world. Its principal texts are not strictly religious, like the New Testament, the Koran, the Talmud, Buddha’s Sutras, and so on; nor are they strictly philosophical. Where western philosophy has its founding texts in Plato and Aristotle, the alternative, heterodox tradition has its own founding texts, the Corpus Hermeticum, the Gnostic Scriptures, and the Chaldean Oracles. In the centuries before the 17th century scientific revolution, three broad streams of heterodox thought – alchemy, astrology, and magic (and sometimes the Kabbalah) – were closely allied to speculation, experiments, and practice in natural science, sometimes through the work of the same thinker. Three outstanding recent scholarly studies of the beginnings of natural science in the Middle Ages (David Lindberg, Edward Grant, and James Hannam) devote lengthy chapters to the significance and impact of alchemy, astrology and magic.

One might argue that the standard history of philosophy began with and developed questions about the relation between how things appear to us and how they really are; then the question how it is that the real world came to be the way it appears, who or what made it that way; and then further, how it is that we can know about the way things really are. In contrast, alternative or heterodox philosophy has always been more concerned with questions about the nature and powers of the human soul, how to train and discipline this inner power, how to manipulate ‘secret’ words and objects to assist in this quest, and methods to achieve higher stages of knowledge in order for the soul to return to its source. However, this book is not a survey of esoteric doctrines (alchemy, astrology and magic), an ambition that has already been achieved several times in recent studies. This book, then, is not a history of something different than philosophy; it is a different history of philosophy.

Another way to think of this project is to compare it with Susan Neiman’s excellent, best-selling book, Evil in Modern Thought: An Alternative History of Philosophy (Princeton, 2002), organised around concepts of and responses to the problem of evil in the modern period, and not around the issue of appearance vs. reality or the problem of knowledge. So, this present book, one could say, is organised around ideas about the mastery of nature’s secrets and the soul’s ascent. This alternative history is like a shadow line, another range of mountain peaks beyond the well-known range, dimly discerned in the distance but now coming more clearly into view. Despite the wide variety and scope of well-respected, scholarly books on individual thinkers and topics, there is no single book that offers an overview of the historical development of alternative philosophy. This book is an impartial, cautious examination of these thinkers’ principal contributions and influences, their associations with one another as well as their antagonisms. Their metaphysics made constant reference to the hidden correspondences between the great world and the small world, the visible and the invisible, an inner nature and its “signature”; their theory of language is one centred on decoding these sacred signs; their theory of mind is one centred on training the human soul to ascend to higher states.

The great political theorist Leo Strauss argued that all major philosophers from Plato the present held public, exoteric doctrines as well as esoteric doctrines, designed for the few, which could be read “between the lines.” According to Arthur Melzer, in his recent book Philosophy Between the Lines, there are four primary kinds of esotericism, either to avoid some evil or to attain some good. In the defensive version, there is some harm to be avoided that society might do to the author or, in the protective version, there is some harm to be avoided that the writer might do to society. If philosophers choose to publish despite considerable dangers then it is for the sake of some good: either, in the political version, for the political (cultural, intellectual or religious) reform of society in general or, in the pedagogical version, for the philosophical education of rare and gifted individuals. In any of these versions the thinker might adopt one of several forms: he might write nothing at all and confine his “secret” doctrines to oral reaching alone; he might produce two different sets of writings for different audiences, one public and open, the other secret and closed to the select few. Or his writings might contain multiple levels, with an exoteric teaching on the surface and an esoteric one “between the lines”, i.e. through hints, codes, special terms, and so forth. Some writers may declare some of the truth of their doctrine and keep other parts hidden, still others will resort to noble lies to keep the general public away from what they really want to say.

Melzer declares that esoteric doctrines are ubiquitous amongst the great names of western philosophy from the very beginning. “To repeat, the real phenomenon, the idea that was once well-known and now forgotten, is this: through most of history, philosophical esotericism has not been a curious exception – it has been the rule. It has been a near constant accompaniment to the philosophic life, following it like a shadow. Furthermore, it has had such relative universality precisely because it derives not from occasional or eccentric circumstances but somehow from the inherent and enduring character of philosophy itself in its relationship to the practical world – from the issue of ‘theory and praxis’.” Melzer has gone to great lengths to trawl through an enormous range of philosophical writings, and presents (in an online appendix) 75 pages of passages from almost every thinker between Homer and Nietzsche where there is an outright declaration of some form of commitment to an esoteric doctrine(s); in the book’s introduction he restricts his testimonies to thirty passages from representative writers from every century – the results are overwhelming. “The single most striking thing about the testimonial evidence is in fact not its quantity but its universality: it just shows up everywhere. It is there in fifth century (BC) Athens and first century Rome, in fourth century Hippo (Algeria), 12th century Cordoba, 13th century Paris, 16th century Florence, and so forth.”

In sum, Melzer finds, “the testimonial evidence for esotericism … turns out to be far more solid than one might initially be inclined to think. Three striking features make the testimony peculiarly powerful: It is massive in extent, universal in distribution, and virtually uncontradicted.” Our project here, in An Alternative History of Philosophy, is much different than Melzer’s project, for the simple reason that Melzer has shown that virtually all philosophers from Plato onwards, over 2400 years, admitted to some form of esoteric teaching, hidden from the many, disclosed to the few. Thus, there is nothing alternative, nothing other than the standard history to be found in what they all kept hidden or undisclosed. The mere fact that, despite how massive and pervasive it is, some doctrines, ideas or theories were kept in the shadows does not by itself constitute a shadowy tradition or traditions.

In Giordano Bruno’s title De Umbris Idearum, ideas were Plato’s archetypes, pure ideal forms, and their shadows were sensible, material things; shadows could also be symbols or signs of these sensible things. But, more importantly from our point-of-view, the principal thinkers in the orthodox, standard history were (or became) so dominate that their ideas cast shadows on other heterodox, alternative thinkers. Hence, one history, one narrative of the development of these ideas (or theories) was clearly shone in the light, the other history in shadow or even darkness. By changing the position of the light source those shadowy figures and their penumbral ideas come more fully into view. In his most recent book, Wouter Hanegraaff captures in a nice image this notion of another domain coming into view. The “continent” of western esotericism “has always been considered the domain of the Other. It has been imagined as a strange country, whose inhabitants think differently from us and live by different laws; whether one felt that it should be conquered and civilised, avoided and ignored, or emulated as a source of inspiration, it has always presented a challenge to our very identity, for better or worse.” Our very identity is as custodians of a standard history or tradition of serious philosophical inquiry. “We seldom realise it, but in trying to explain who ‘we’ are and what we stand for, we have been at pains to point out that we are not like them. In fact, we still do.”

The eminent American philosopher Richard Rorty had a mad idea, one he held strongly until his death in 2007, an idea which he never had the chance to pursue. In his memoir of his friend, Raymond Geuss recalls that Rorty once described to him a new course which he hoped to give one day. It was to be called “An Alternative History of Modern Philosophy” and would sketch “a continuous conversation from the end of the Middle Ages to the beginning of the 20th century without once naming any of the standard, canonical figures. It was to start with Petrus Ramus [and] some of the high points were to be Paracelsus, the Cambridge Platonists, Thomas Reid, Fichte, and Hegel.” Rorty held that “there is no such thing as a universal set of philosophical questions or issues; Paracelsus wasn’t remotely interested in asking or answering questions like those we find in ‘philosophy’; still, lots of people at the time thought his work a paradigm of what a philosopher should be doing.” Rorty thought that philosophy “at different times and places referred to different clusters of intellectual activities, none of which formed a natural kind and none of which had any ‘inherent’ claim to a monopoly in the ‘proper’ use of the term ‘philosophy’. Doing a history in which Paracelsus figured centrally, but not Descartes, could be seen as a part of trying to give a history, not so much of philosophy, as of historically differing conceptions of what philosophy was.”

Rorty had already broached the idea of an alternative history in his paper for the collection Philosophy in History. Here he said that an intellectual history would include “those enormously influential people who do not get into the canon of great dead philosophers, but who are often called ‘philosophers’ either because they held a chair so described, or for lack of any better idea – people like Erigena, Bruno, Ramus, Mersenne, Wolff, Diderot, Cousin, Schopenhauer, Hamilton, McCosh, Bergson and Austin.” Names in this list undoubtedly reflect, to some degree, Rorty’s own view of what counts as “a better idea” for inclusion – but the underlying insight remains. “Discussion of these ‘minor figures’ often coalesces with thick description of institutional arrangements and disciplinary matrices, since part of the historical problem they pose is to explain why these non-great philosophers or quasi-philosophers should have been taken so much more seriously than the certifiably great philosophers of their day.” This issue will come up again when we consider Collins’ Network Paradox (below): the most famous thinkers were accorded the highest canonical status and their fame rested on the density of their connections with other famous thinkers. Rorty also wants to include ‘borderline’ cases of the species of philosopher, para-philosophers who impelled social reform, supplied new moral vocabularies and deflected scientific or literary disciplines into new channels. These would include: Paracelsus, Montaigne, Grotius, Bayle, Lessing, Paine, Coleridge, von Humboldt, R. W. Emerson, T. H. Huxley, and others.

Rorty carried on in the same vein: “Once we drop below the skipping-from-peak-to-peak level of Geistesgeschichte to the nitty-gritty of intellectual history, the distinctions between great and non-great dead philosophers, between clear and borderline cases of ‘philosophy’ … are of less and less importance.” For example, the question of whether one includes Francis Bacon and excludes Robert Fludd is an issue that to be settled after an intellectual history has been written and not before. “Interesting filiations which connect these borderline cases with clearer cases of ‘philosophy’ will or will not appear, and on the basis of such filiations we shall adjust our taxonomies.” New paradigm cases of philosophy will produce new nodes within these networks (as we shall call them) and hence the networks will be reformed. “Like the history of anything else, history of philosophy is written by the victors. Victors get to choose their ancestors, in the sense that they decide which among their all too various ancestors to mention, write biographies of, and commend to their descendants.” The version of canonical history that Rorty deplores is “the genre which pretends to find a continuous streak of philosophical ore running through all the space-time chunks which the intellectual historians describe; [it is] relatively independent of current developments in intellectual history. Its roots are in the past – in the forgotten combination of transcended cultural needs and outdated intellectual history which produced the canon it enshrines.”

Historical reconstructions which work with thick, rich descriptions remind us of “those quaint little controversies the big-name philosophers worried about, the ones which distracted them from the ‘real’ and ‘enduring’ problems which we moderns have managed to get in clearer focus. By so reminding us, they induce a healthy skepticism about whether we are all that clear and whether our problems are all that real.” Recent scholarly studies of non-great thinkers – heterodox, esoteric, marginal philosophers – show that the thinkers we often take to be the most important were often less influential than others whose names have faded. “They also make us see the people in our current canon as less original, less distinctive, than they had seemed before. They come to look like specimens reiterating an extinct type rather than mountain peaks.”

In his recent book The Occult Mind (2007), Chris Lehrich situates this alternative tradition in the historical development of occult, magical and esoteric traditions, despite the fact that “modern academe does not recognise a discipline devoted to the analytic study” of these traditions. “Work in these areas”, he states at the outset, “though on the increase, remains hampered by various methodological and political blinders. The primary difficulty is simply explained: work on magic is tightly constrained by the conventions of the disciplines in which it is locally formulated.” Magic in the early modern period, for example, “receives treatment within the narrow limits of intellectual history and the history of science. Most books advert to normative modes of evidence, analysis, and interpretation in those historical fields.” Other academic disciplines when they treat these alternative domains present their studies according to their own disciplinary models. However, “some important potential contributors, notably philosophers, have not as yet seen a reason to join the conversation.” Academic scholars working with texts in these traditions “have often been strikingly anxious to situate themselves indisputably within a conventional disciplinary framework, as though thereby to ward off the lingering taint of an object of study still thought disreputable if not outright mad. Many have encountered hostility, or amused disdain, from colleagues in more accepted fields. Thus, it is no surprise that scholars of magic bend over backward to demonstrate just how ‘straight’ they are.” Lehrich declares that it is no longer necessary – given the outstanding contributions of scholars in the last fifty years – to defend the legitimacy of scholarly studies of occult, magical and esoteric traditions.

It is important however, to distinguish this alternative history of philosophy from history of esoteric doctrines, i.e. from a comparative history of alchemy, astrology, magic, and Kabbalah. Further, to adumbrate such an alternative history is not an endorsement of any kind of perennial philosophy or pristine wisdom tradition. Charles Schmitt has carefully separated these two streams: “The concept of prisca theologia indicates that the true knowledge would be anterior to Greek philosophy and would actually be found, although perhaps in an enigmatic and esoteric form, among the pre-Classical sage such as Zoroaster, [Hermes] Trismegistus, and Orpheus. Usually it is thought that, directly or indirectly, they derived their wisdom from Moses, and therefore they assumed a high level of authority within the Jewish-Christian tradition.” The prisca sapientia passed from Orpheus to Pythagoras to Plato. Hanegraaff comments that the rediscovery and translation of the lost writings of Zoroaster, Hermes and Orpheus in the later 15th century was a momentous event with millenarian overtones. “For the first time in history … Christians had been granted access to the most ancient and therefore most authoritative sources of true religion and philosophy; surely the hand of providence was at work here, showing humanity a way towards the needed reformation of Christian faith by means of a return to the very sources of divine revelation.”

Schmitt further distinguished prisca theologia from philosophia perennis; the latter, he said, “makes wisdom originate in a very ancient time, often applying the same genealogy of the transmission of sapientia like the prisca theologica, but it also puts emphasis on the continuity of valid knowledge through all periods of history. It does not believe that knowledge … has ever been lost for centuries, but believes that it can surely be found in each period, albeit sometimes in attenuated form.” This second perspective strongly underscores the unity and universality of wisdom rather than its decline, and thus lacks the millenarian implications of the first view’s outlook. Hanegraaff comments that between these two viewpoints there is “a strong tension between two opposed tendencies: on the one hand, a historically oriented narrative of ancient wisdom which held considerable revolutionary potential, and, on the other, an essentially conservative doctrine which preaches the futility of change and development by emphasising the trans-historical continuity and universality of absolute truth.” Hanegraaff claims that he discerns a third tendency; “the one that claims that, due to divine inspiration, the ancient philosophers before Christ had been granted prophetic glimpses into the superior religion of Christianity. Such a third option, which might be conveniently referred to as pia philosophia, introduces an element of ‘progress’; whereas the prisca theologia combines a narrative of decline with hopes of imminent revival, and philosophia perennis emphasizes continuity, pia philosophia thinks in terms of growth and development, imagining a gradual ‘education of humanity’ to prepare it for the final revelation.” This third tendency’s actual relevance to Renaissance culture remains somewhat limited, contrary to the other two tendencies; “it concerned a period that had ended with the birth of Christ, and therefore had little social or political relevance for the present: neither revolutionary nor conservative in its implications, it amounted to little more than a historical opinion concerning a time that now belonged to the remote past.”

In Hanegraaff’s conclusion, there are three mutually exclusive macro-historical schemes: evolution, degeneration, and continuity. “The evolutionary or educational perspective, which appreciated ancient wisdom only as praeparatio evangelica, was most obviously orthodox but implicitly minimised the relevance of studying the newly discovered sources; as a matter of principle, anything of value that they might contain was believed to be expressed more fully and clearly by Christian theology, and anything not included in it had to be pagan error by definition. Starting from a very similar assumption of Christian doctrine as the self-evident truth, the perspective of philosophia perennis emphasized its universality, sometimes to the point of embracing a perspective of ‘everyone is right’, but the implication was again that the study of the new sources could not possibly yield any new insights, but could only ever provide more confirmation of truths already known.” Critics had good reason to fear that the new sources might contain the seeds of the Christian religion’s destruction and its replacement by a revived universal pagan religion.

Since we are here attempting to distinguish what we have chosen to call the alternative philosophical project from the history of esoteric doctrines, it is important to clarify the ways in which “esoteric” (hidden or secret) has been distinguished from “exoteric” (public or overt). The French scholar Antoine Faivre, in numerous important works from the 1960s onwards, began by employing this distinction in an entirely conventional way. To begin with he emphasised the notions of an Inner Church, initiation into mysteries, the myth of fall and return, and the centrality of nature as a web of correspondences. In his first general overview of “Christian esotericism” from the 16th to the 20th century, “one sees him struggling with the various connotations of the word and the difficulties of demarcating the field. His proposal … was to define as ‘esotericist’ any thinker, ‘Christian or not’, who emphasised three main points: analogical thinking, theosophy, and the Inner Church. Faivre made a point of demarcating esotericism not only from witchcraft, but also from magic, astrology, and the mantic arts: these ‘occult’ arts qualified as esotericism only insofar as they appeared in a theosophical context.” He viewed the field marked out as one dominated by an “illuminist” context, with its immediate roots in Paracelsus, Christian Kabbalah, and Jacob Böhme. At the end of his article he stated that, “comprehending the spiritual events of esotericism is not possible without a hermeneutics that always leads back to the archetypal plane, for a meaning has its own proper value, independently from all the explications that one can – and must – give it; as such, this meaning should neither be reduced to one fixed literal interpretation, nor enclosed in a history that is seen as belonging to the past.”

Faivre discussed alchemical texts as reflections of an underlying worldview, and applauded Mircea Eliade for having demonstrated that “the historical perspective alone, although absolutely indispensable in any serious study, is powerless to give an account of certain spiritual facts.” To truly understand alchemy “which imagines always in space, almost never in time, one needed a non- Aristotelian and non-Cartesian logic.” In his major work Esotericism in the 18th Century (1973), Faivre confidently stated that “esoteric thought appears to be of an essentially contradictory type, that is to say, it is made up of symbolic mechanisms that belong to the logic of contradiction.” He claimed that esotericism must be understood in terms of the analogical thinking proper to myth and symbolism, not the Aristotelian logic proper to philosophy and doctrinal theology. In Hanegraaff’s summary, “The theosophers or esotericists tended to be badly understood because they either speak their own language, which is understood only by their peers and by poets, or try to make themselves understood in the inadequate language of the philosophers and theologians. Faivre tried to demarcate his own approach from two types of dogmatic either/or thinking, those of traditionalist esotericism and rationalist reductionism; and presented ‘esotericism’ as a kind of mental space mediating between the radical homogenising extremes of dualism, ecstatic mysticism, and the established churches.”

Faivre argued that the logical principles of identity, non-contradiction, and the excluded middle had come to be applied to metaphysics as well as natural science. This logic has turned into “an intolerant master” that excluded any other approach to reality as deficient apriori, and as a result what is now called “esotericism” emerged as a category of exclusion. These forms of thinking coalesced into a strange mass of textual material called esotericism about a century ago and “is still seen by many as just a cabinet of curiosities where the best rubs shoulders with the worst. Sometimes without any transition, next to the low magic or the delirious divination of a sorcery inherited by last century’s occultism, one discovers there the summits of human thinking, intuitions on man and the universe that are capable of bursting open the deadlocks in which our modern philosophers have indifferently allowed themselves to get imprisoned.”

The repression of analogical thinking, and its allied methods, “resulted in an artificial opposition that left room only for two extremes: either an abstract idealism focused only on pure divine essences or a concrete visible universe cut off from any spiritual reality (finally leading to materialism). … The destruction of an organic harmony uniting God, man, and the world resulted in a continuing situation of existential malaise that remains characteristic of the ‘idealist… intellectualism of modernity’.” Faivre’s article culminated in an appeal for remythologisation and revaluation of the ‘creative and participatory imagination’, against such contemporary trends as existentialist pessimism, the abstract formalism of structuralism, the superstition of materialism, and the nihilism of an ‘archaeology of knowledge’ that tries to convince us that ‘knowledge sounds hollow, man is dead, nature is meaningless, and no philosophy has any sense.” Faivre’s strong criticisms were directed at “the desacralisation of the world, the reversal of values that made ‘above’ a reflection of ‘below’ instead of the reverse, historical concepts of linear causality, the blind faith in secular evolution and progress, and so on; against all forms of ‘reductionism’, he was affirming that myth should have precedence over history, metaphysics over physics, correspondences over causality, analogical thinking over Aristotelian logic and images over concepts.”

When it comes to major thinkers in Renaissance philosophy it quickly becomes clear that the usual distinctions, those embedded in post-Enlightenment histories, no longer hold: between orthodox and heterodox, between standard and alternative, exoteric and esoteric. It seems like an entirely artificial, post-hoc rationalisation to separate out one side from another in Ficino or Pico or van Helmont. In their recent book on Heterodoxy in Early Modern Science and Religion (Oxford, 2006) the editors John Brooke and Ian Maclean are quite clear about this in their Preface. “Most early modern writers who venture into areas in which it is important to determine where they stand on contentious scientific and religious issues set down or imply their own relationship to the orthodoxies of their day.” The topics that thinkers from all over Europe discussed “concerned the soul and the nature of matter… cosmology, eschatology, and the question of human destiny… and the confrontation of the new philosophers of the later 17th and 18th century with Christian beliefs and writings…. These issues are related to others which occur in many of the writings discussed, notably the nature of God and his ways of intervening in his creation, and the meaning to be attributed to statements found in Holy Writings about the universe (Mosaic physics).” It should be obvious that most, if not all the “hot topics” mentioned are just as well situated in “standard” themes of philosophical discourse as they are in these heterodox domains.

Brooke and Maclean tell us that the supposed discord or mismatch between an orthodox and heterodox point-of-view on one of these topics has sometimes been called ‘paradox’. But the very idea of paradox, an opinion or belief ‘around’ two views, “did not only denote departure from established doctrine; it also referred to the new knowledge that was emerging in the course of the 16th century in the works of ‘neoterici’ [“newbies”] who cited new data, or produced new theory, or did both …. In the sphere of natural philosophy new knowledge could take various forms; it could be the recovery of ancient doctrines which had been lost, discarded, neglected, or forgotten (such as atomism); it could be the logical extension of the work of the ancients (mathematics and mechanics); it could be radical revision of Aristotle’s physics and cosmology, as in the work of Copernicus, Brahe, and Kepler.” In the early 17th century, “it seems here that ‘heterodox’ designates either an existing alternative version of a doctrine, or a deviant view which is different from, but not radically contrary to, an existing dogma, or an opinion expressed by someone else on a subject on which no doctrine of an authoritative kind is on record.” (Note “alternative”)

One has to go back nearly a hundred years to find a more inclusive history of western philosophy: Heinz Heimsoeth’s The Six Great Themes of Western Metaphysics (first German edition 1922). Heimsoeth begins by declaring how amazed he is that the history of philosophy has been so little concerned with reviewing traditional classifications; how much it has simply taken over from textbooks of general intellectual and cultural history. “How seldom are the great arteries of development here really chiseled out from proper material, the philosophical problems themselves.” This history began in the ancient world as worldly wisdom, free science about the essence of natural things; but in the Middle Ages philosophy as the handmaid of theology elaborated dogmatic religious truths. The Renaissance changed all that, ushering in a freer age in which science knew nothing of coercion and obfuscation. Ancient philosophy came to life again, mediated by Greek scholars who migrated from Byzantium to the West, bringing with them the triumph of Plato and inspiring the rebirth of classical ideas in Italy. And from the Italian Renaissance sprang the English Renaissance, and then the French Enlightenment, and from Descartes “issued everything decisive: Hobbes and Locke, Spinoza and Leibniz.” But sadly, for this story, “Germany arrived altogether last on the scene. Torn by religious strife, it was unable for a long time to enjoy the freedom of the new ancient thinking.” It was not for another two hundred years that the ground was cleared for the German system of Leibniz. “But there are extremely serious objections to this construction if one investigates the ultimate contents and themes of the systems themselves with respect to their tendency, origin, and importance.”

If one examines the Italian Renaissance in terms of its own achievements the picture changes: “Speculative power and true metaphysical talent lag strikingly behind nimbleness of creative imagination, fiery impetus of expression, and dazzling abundance of material picked up from everywhere.” Few periods in the history of philosophy are “so fragmented, so inwardly insecure in simultaneous adherence to the most diverse traditions, so indiscriminate and without a proper estimation of magnitudes, even in comprehending the legacy of the ancients.” Everything in this period of any worthy or lasting value points to something else as its source. Heimsoeth offers Giordano Bruno as an outstanding example of his thesis: Bruno did not acknowledge as his inspiration or source the Italian humanists or the ancients, but rather three German thinkers – Copernicus, Paracelsus, and Nicholas of Cusa. It is well known that Bruno had a decisive influence on Leibniz’s thought – the monad, vital force, infinite space, plurality of worlds, etc. – so Leibniz can be thought of as “the carrier and shaper of an indigenous German tradition”, one descended from Bruno. And what about the origins of the dominant ideas in Bruno, Paracelsus and Nicholas of Cusa? Heimsoeth declares that it is German mysticism, especially that of Meister Eckhart, which was the German philosophy of the late medieval period. The continuer of this indigenous mysticism in the Reformation period was Jacob Böhme, “compared to whom all contemporary philosophy of the Humanists sinks into nothingness, [he] was called simply the philosophus teutonicus.”

Those centuries in German thought prior to Leibniz “were not poor and constricted, dependent on foreign achievement, and without any native power; on the contrary, they were rich and free and great, perhaps more original in the directions of their thought than the high-sounding proclamations of the Renaissance and Humanism.” Having brought into the foreground many significant German thinkers, Heimsoeth is confident that an informed, internally consistent history of modern philosophy is not just “a chain of finished systems and isolated peaks”. He declares that, “What it is that cogently determines a period’s or a people’s attitude toward life – at a level below the obvious tradition of books and theories that have matured into systematic concepts – is something the importance of which one can subsequently easily underestimate when compared with the strident words of those who assume the role of speaker for something that has grown up quietly.”

And this brings us to the tricky question of how the standard philosophical history is formed and how any alternative history can be constructed. In his enormous, exhaustive book The Sociology of Philosophies (2000) Randall Collins identifies and defines the crucial notion of focal point or centre of attention. “The social structure of the intellectual world … is an ongoing struggle among chains of persons, charged up with emotional energy and cultural capital, to fill a small number of centres of attention. Those focal points, which make up the cores of the intellectual world, are periodically rearranged; there is a limited amount of attention that can be distributed through the total intellectual network, but who and what is in those nodes fluctuates as old intellectual movements fade out and news ones begin.” Collins visualises these nodes in an intellectual “space” or frame articulated by lines of affinity, descent or conflict. “These nodes in the attention space are crescive, emergent; starting with small advantages among the first movers, they accelerate past thresholds, cumulatively monopolising attention at the same time that attention is drained away from alternative nodes. The identities that we call intellectual personalities are great thinkers if they are energised by the crescive moment of dominant nodes of attention, lesser thinkers or indeed no one of note if they are not so energised, are not fixed.”

This criterial definition is the one upon which the Network Connection Paradox depends; minor figures are defined by lack of this energy; and “energy” as such is another name for shared interests, themes and problems. “It is precisely because the social structure of intellectual attention is fluidly emergent that we cannot reify individuals, heroising the agent as if each one were a fixed point of will power and conscious insight who enters the fray but is no more than dusted by it at the edge of one’s psychic skin. The reified individuality can be seen only in the retrospective mode, starting from the personalities defined by known ending points and projecting them backwards as if the end point had caused the career. My sociological task is just the opposite: to see through intellectual history to the network of links and energies that shaped its emergence in time.”

Collins provides 56 detailed charts of networks of philosophers, epoch by epoch (or century by century): Greek and Roman, Islamic, European, Chinese, Indian, and (later) American figures. In each chart, major or dominant thinkers’ names are in all-capitals, secondary thinkers in lower case, and minor thinkers (usually) identified with numbers (whose names and occupations are given in an appendix). Collins states that, “the most notable philosophers are not organisational isolates but members of chains of teachers and students who are themselves known philosophers, and/or of circles of significant contemporary intellectuals. The most notable philosophers are likely to be students of other highly notable philosophers.” As well as across generations, “creative intellectuals tend to belong to groups of intellectual peers, both circles of allies and sometimes also of rivals and debaters.” One important point to emphasise here is the use of the word “notable” – an epithet assigned to those who have the greatest number of connections. Collins identifies or even defines “major” as those who have the greatest number of “links” with other philosophers, but especially with other major figures, both “upstream” (predecessors) and “downstream” (successors). This picture leads to what could be called the Network Connection Paradox.

Let’s focus our attention on Figure 10.1: “European Network: The Cascade of Circles 1600-1735”. It is an intricate nest-like diagram of names connected by lines, where different types of line indicate different relations: acquaintance, master-pupil relation, probable relation, or conflictual relation. In some places, the diagram shows a nest of smaller nests; over 200 individuals are indicated: 12 names are in all-capitals for influential first-rank philosophers, with names in round brackets for equivalent first-rank non-philosophers (scientists); about 40 names are in lower case, with some names in round brackets, as before; and the remainder (163) indicated by number only, with their names and affiliations listed in an Appendix. Around the primary and secondary names clusters of lines converge from other thinkers, primary and/or secondary, the line-clusters denser around the primary thinkers; from minor thinkers only one or two lines lead in or out.

It quickly becomes apparent that the standard history of western philosophy is outlined or diagramed by the linkages amongst major philosophers whose names are in all-capitals, sometimes by way of secondary figures. But it’s here that the problem or paradox emerges: major thinkers are defined by the number of links with other major or secondary thinkers – links of affiliation, influence or opposition, but at least links that show direct engagement. These notable thinkers are those “energised by the crescive moment of dominant nodes of attention”. The content of these links is formed from sharing similar topics, points-of-view, methods, backgrounds, etc. Minor thinkers are minor because they have fewer links, and they have fewer links because they are outliers, mavericks, rebels, etc. who do not share some or all of these dominant concerns. In a word, they are called minor because they are heterodox thinkers in an alternative tradition. Thus, the process of formulating a chronological, multi-stage picture of the main figures is circular to some degree: major figures are defined as those with the most links upstream and downstream, where the links are made due to these thinkers’ compatibility or shared allegiance on those topics, themes, and concerns. It’s not that links are made to thinkers who are “notable” for other independent reasons, but rather that the number of links made to notable thinkers constitutes their notability. Thus, the Network Connection Paradox is that what permits any given thinker to count as a major figure (i.e., his eligibility criterion) is the high density of links up and down; the standard history is the overall “picture” of these dense linkages epoch by epoch; but the density of links is itself the result of the shared themes, concerns, and points-of-view and these are not independently established or justified.

According to Antoine Faivre, Western Esotericism can be identified by the presence of six basic factors: the first four factors are intrinsic, together comprising necessary and sufficient conditions; the last two factors are relative to social-cultural conditions. First, the esoteric stream posits systems of symbolic correspondence among all parts of the visible and invisible universe; they are not obvious at first glance but instead are veiled; they need to be read or deciphered. “The universe is a theatre of mirrors, a mosaic of hieroglyphs to be decoded; everything is a sign, the least object is hiding a secret.” Second, according to the idea of living nature, “the cosmos is not merely complex, plural and hierarchical, it cannot be reduced to a network of correspondences [since] it is also alive.” The concept of nature is one that is thought to be living (or dynamic) in all its parts; it is pervaded by a light or fire which circulates through all natural forms. Natural magic is closely attached to this living nature, since it operates through hidden forces by means of the manipulation of seals, talismans, stones, metals and plants. Third, the idea of symbolic correspondence implies that humans have an imaginative faculty capable of deciphering these hieroglyphs, i.e. seeing the true signatures of things.

These signatures always present themselves more or less as mediators between the perceptible datum and the invisible or hidden thing to which it refers. Rituals, images, and symbols are mediators since they allow the various levels of reality to be reconnected to one another through the operator’s actions. Human imagination is a cognitive power that allows intermediaries to be used for “Gnostic ends”; it is “a sort of organ of the soul” through which a human can establish an intellectual relation with the mesocosm, “an imaginal world”. Faivre comments that it is only after the rediscovery of the Hermetic corpus at the end of the 15th century that memory and imagination are privileged in the cognitive discipline of the adept. Fourth, in addition to the idea of visionary insight coupled with living nature is the personal experience of something like initiation, the experience of transmutation. What is called “gnosis” is often this illuminated knowledge that favours a second birth through a process of substantial change. An interior transmutation follows the path marked out in alchemical terms: nigredo (blackening = death), albedo (whitening = change), and rubedo (reddening = new life). Faivre says that one is tempted to compare these three phases with the three stages of mystical knowledge: purgation, illumination, and unification.

The fifth factor pertains to the practice of concordance; closely akin to the basic idea of philosophia perennis, this notion posits the existence of common denominators amongst several traditions, then studies them in the hope of bringing out the forgotten or hidden trunk of which each manifest tradition would be a branch. The sixth factor pertains to the practice of transmission: by means of various channels, the basic ideas of the hidden tradition are passed from one initiate to another, either from master to disciple or amongst members of a secret society. The idea is that one cannot be initiated by oneself alone and that a second birth requires training. This may lead to the idea of authenticating, giving credentials for, specific channels of affiliation. “The mystic – in the very classical sense – aspires to a more or less complete suppression of images and intermediaries (mediations) because they quickly become obstacles for him to union with God. This, in contrast to the esotericist, who seems more interested in the intermediaries revealed to his inner vision by virtue of his creative imagination than in tending above all to a union with his God. He prefers to sojourn, to travel, on Jacob’s ladder, where the angels – the symbols, the mediations – are ascending and descending, rather than venture beyond.”

One of Faivre’s more intriguing conjectures concerns the origin of the main figures in theosophy (such as Paracelsus) from Lutheran soil, a thesis for which he elicits several contributive conditions. (1) Lutheranism allows free inquiry, an openness which in certain inspired souls can take the form of prophecy. (2) It embodies a paradoxical blend of mysticism and rationalism, whence the need to bring inner experience into discussion, and conversely to listen to discussions and transform them into inner experience. (3) Less than a century after the Reformation, the spiritual poverty of Protestant preaching and the dryness of its theology were sorely resented and this also spurred the need for revitalisation. (4) In the milieus where Lutheran theosophy was born there was some freedom of expression and observance for its ministers, but at the same time prophetic activity as such was not well tolerated. In the 17th century the ideal of solidarity among thinkers began to be realised; a community of effort amongst philosophers made the very notion of a total science seem feasible. “Theosophy is globalising in its essence; its vocation demonstrates an impetus to integrate everything within a general harmonious whole.” This epoch also witnessed new theories about the nature of language and the meaning of signs; knowledge of divine things was gained by investigation of the concrete world where God’s plan could be read in signatures and hieroglyphs, provided one had the proper natural scientific training. In sharp contrast with the material-mechanical model of explanation in Descartes and Galileo, theosophy continued the long Platonic and Neoplatonic tradition of explanation in terms of a dynamic model of reality.

Faivre has touched upon one of the most significant features of what we propose to call an alternative or heterodox history of ideas, viz. the commitment to an imaginal world, midway between the sensible and the intellectual, or between the material and the spiritual. The most detailed and influential research in the history and theory of this idea is from the work of the French scholar Henri Corbin who argued for its appearance in Shia Islamic mystical writings of the 12th century. In one his most famous papers on this idea, Corbin said that between the empirical world of things and the abstract world of ideas “there is a world that is both intermediary and intermediate, described by our authors as the ‘alam al-mithal, the world of the image, the mundus imaginalis: a world that is ontologically as real as the world of the senses and that of the intellect. This world requires its own faculty of perception, namely, imaginative power, a faculty with a cognitive function, a noetic value which is as real as that of sense perception or intellectual intuition. We must be careful not to confuse it with the imagination identified by so-called modern man with ‘fantasy’, and which, according to him, is nothing but an outpour of ‘imaginings’.” In the original Arabic this world is called the “eighth clime”, i.e. beyond the spheres of the seven planets; it signifies a clime outside all climes, a place outside all places, and hence might be called utopia. The Islamic mystics’ approach to the creative imagination, “which had always been of prime importance for our mystical theosophers, provided them with a basis for demonstrating the validity of dreams and of the visionary reports describing and relating “events in Heaven” as well as the validity of symbolic rites. It offered proof of the reality of the places that occur during intense meditation, the validity of inspired imaginative visions, of cosmogonies and theogonies and above all of the veracity of the spiritual meaning perceived in the imaginative information supplied by prophetic revelations.”

In the Introduction to his 1969 work Alone with the Alone (based on his Eranos Lectures from 1955-56), Corbin expresses his thesis this way: “between the universe that can be apprehended by pure intellectual perception and the universe perceptible to the senses, there is an intermediate world, the world of idea-images, of archetypal figures, or subtle substances, of ‘immaterial’ matter. This world is as real and objective, as consistent and subsistent as the intelligible and sensible worlds; it is an intermediate universe ‘where the spiritual takes body and the body becomes spiritual’, a world consisting of real matter and real extension, though by comparison to sensible, corruptible matter these are subtle and immaterial. The organ of this universe is the active imagination; it is the place of theophanic visions, the scene on which visionary events and symbolic histories appear in their true reality.” The interpretive level or layer of this imaginal world “is essential symbolic understanding, the transmutation of everything visible into symbols, the intuition of essence or person in an image which partakes neither of universal logic nor of sense perception, and which is the only means of signifying what is to be signified.”

According to Eric Voegelin the imaginal world figures largely in Hegel’s attempts to found philosophy as a religion beyond Catholic and Protestant ideologies. Hegel had diagnosed his present age as one of both diremption and boredom: “the Sabbath of the world has disappeared and life has become a common, unholy workday.” In discerning the ways in which human life has been desacralised Hegel had to exempt himself from its boredom. As a philosopher, he had to be spiritually healthy enough to diagnose the spiritual state of society as diseased. He also had to reconcile and embody in himself the pneumatism of the inner man and the inner light. The third factor in Hegel’s overcoming of the present age is “the imaginative construction of ages that will permit the imaginator to anticipate the future course of history. By means of this construction, the imaginator can shift the meaning of existence from life in the presence under God, with its personal and social duties of the day, to the role of functionary of history; the reality of existence will be eclipsed and replaced by the Second Reality of the imaginative project. In order to fulfil this purpose the project must first of all eclipse the unknown future by the image of a known future; it must further endow the construction of the ages with the certainty of a science… and it must, finally, conceive the future age in such a manner that the present imaginator becomes its inaugurator and master. The purpose of securing a meaning of existence, with certainty in a masterly role betrays the motives of the construction in the imaginator’s existential insecurity, anxiety, and libido dominandi. This is megalomania on the grand scale.”

If one highlights alternative thinkers such as Ramon Llull, Roger Bacon, the Picatrix, Paracelsus, Agrippa, John Dee, Abbot Trithemius, and Jacob Böhme their commitment to the powerful force of the active, creative imagination is obvious; their imaginal world is peopled by a vast array of spiritual entities, animate and animate, halfway between material and immaterial, concrete and abstract. The ‘objective correlate’ of creative imaginings are the visible signs or symbols which express the ‘objects’ of these intense trance-like or meditative states. Alternative thinkers are much more likely than others to make use of diagrams, charts, and illustrations to represent these imaginal entities and their structural relations, to express in a pictorial manner what they have said in the text. In The Alchemy of Light (2000) Urzula Szulakowska links the Renaissance idea of alchemical illustration to C.S. Peirce’s concept of the index: “a sign or representation which refers to its object not so much because of any similarity or analogy with it, nor because it is associated with general characters which that object happens to possess, as because it is in dynamical (including spatial) connection both with the individual object … and with the senses or memory of the person for whom it serves as a sign.” An index then is “not a simulacrum ‘more real than real’, for it’s intended to be an uninterrupted continuation of the real, a deliberately composed ambiguity concealing the distinction between reality and artifice.”

Szulakowska singles out John Dee’s cipher for the Monas Hieroglyphica as the epitome of the “visual index”, as also are Robert Fludd’s cosmological diagrams. “At first glance, Fludd’s diagrams appear to be symbolic (merely illustrating his text) but, in fact, they also have an iconic aspect, since they can be isolated from their textual context while retaining most of their meaning. In addition, as indexical generators of a contemplative type of alchemy, some of Fludd’s pictures were meant to integrate the viewer into their imaginary world, causing a spiritual and intellectual alchemy to occur in the moment of viewing the image.” Szulakowska selects an obscure Augsburg imprint from 1615 to show how this graphic trend could reach remarkable heights; “where the ever-increasing complexity of structure was designed for lengthy perusal [it] eventually eliminated the physical aspects of alchemy altogether.” The Augsburg book is “one of the earliest of these imaginative alchemies, luring the viewer through the glass of his four fiery and jewel-like ‘mirrors’ into the higher intellectual and spiritual realms of the alchemical discourse. When the viewer emerged from the trace-like state induced by participation in [his] visions, he was (perhaps) transformed, like base matter, into spiritual gold. Effectively, alchemical illustration in the 17th century was usurping the transmutatory function of the philosopher’s stone. The sophisticated graphic repertoire of Renaissance artists enabled them to manipulate the semantics of their pictorial elements, producing imagery which could induce meditative or visionary states in their viewers, uniting them with the depicted visions.”

Another outstanding exemplar of alchemical illustrative power would be Paracelsus and his disciples and imitators. Szulakowska points out that Renaissance artists’ increased sensitivity to “the topography of the picture-plane enabled him to weave together naturalistic and geometrical elements into a visually and conceptually coherent field.” By splitting the two-dimensional picture-plane into layers of realistic and abstract from the artist was able to unite them by means of perspectival geometry. This meant that the picture could be read at the same time at both the representative and the abstract level, “as if the viewer was being presented with a vision of the numinous being implicated within the gross fabric of the natural world.” And this function expressed the essence of Paracelsian theosophy in which the physical world was the emanation of the celestial spheres. “Paracelsian alchemical engravings were intended to be theosophies, i.e. they were meant to promote prolonged contemplation leading to ‘gnosis’, a wisdom inspired by the heavens.”

In contrast, earlier alchemical imagery was a shorthand symbolic system, designed to clarify and deliver information as quickly and simply as possible. Paracelsus, on the other hand, had given the human imagination “a structural role in his theurgy and thereby in his cosmology.” He had taught that human being, as a mirror of the cosmic order, had two bodies, one physical the other astral; the active imagination was a faculty of the astral body. “It was only due to the existence of the celestial spheres within the human body as its innate ‘astra’ that the human being could understand the stars. … Paracelsus conceived of human intelligence as merging with its object of study, so that it gained knowledge, not by rational logic, but through an empathetic union with the world, that is, through ‘gnosis’.” In Paracelsian theosophy, empathetic imagination was not a subjective or negligible factor in human affairs, but a powerful astral force that provided the basis for theurgy, prophecy, and mystical inspiration. Paracelsus stated that through the astral body’s imaginative faculties a human could attain beatific union with God.

Szulakowska claims that Heinrich Khunrath in his Amphitheatrum of 1595 also offers landmark examples of this form of illustration. “His engravings are intended to excite the imagination of the viewer so that a mystical alchemy can take place through the art of visual contemplation.” His amphitheatrum is a kind of spectaculum and a spectacle is a mirror of sorts. She says that in contrast with illustration in the Middle Ages, by the late Renaissance, “the picture could be read simultaneously at both the representational and the abstract level, as if the viewer was being presented with a vision of the numinous being implicated within the gross fabric of the natural world.” Pictorial imagery could stand independent of the text; imagery of this type was able to communicate in either an iconic or an indexical format. She also says that alchemical geometry in the Renaissance can be described as passive or operative, either using geometrical structures to organize information into tabulations, circular formats, or tree-like structures or, as in the case of pseudo-Llullian alchemy, employing a mobile computation system. Another more complex type of alchemical geometry emerged in the late 16th century based on optical and perspectival diagrams which interrelated Pythagorean geometry, optical science, Paracelsian alchemy and Cabbalism.

Another way of seeing the exoteric-esoteric distinction is at work in the Gnostic Scriptures. In Hidden Wisdom, G. G. Stroumsa offers us a way to understand the baffling profusion of characters, speeches and ideas in at least one dimension of Gnostic scriptures. He points out that the esoteric character of Gnostic mythology has so far elicited little scholarly attention, but reveals something quite distinct about the Gnostics’ approach to knowledge and truth. The Gnostics carried forward pagan ideas about hidden, secret teachings, but transformed them into mythic stories – concepts dressed up as narratives. Where myths about the gods and mortals were exoteric and accessible to all, the core rituals of mystery cults were esoteric and accessible only to initiates. With the emergence and establishment of the Christian religion, however, myths and riddles disappeared, replaced by the Christian mystery. The practice of interpretation of myths was replaced by Biblical exegesis of texts; Holy Scriptures were revealed teachings, perfect expressions of the whole truth. For the Gnostics, however, students were adepts who had to learn step by step the message underlying these baffling stories. And that, to some extent, is what we as readers have to do from the start of our investigation.

Image