Marie Spartali as Hypatia, 1867, Albumen print by Julia Margaret Cameron

Originally posted 21.03.14

Emails sent to ABC Radio National – I did not receive a reply to either.

To Alan Saunders, ‘The Philosopher’s Zone’ ABC Radio National, 03.09.09: ‘Knowledge or “god” ’

Hi Alan,

On 18.10.08 Graham Priest said on your program:

‘I mean one of the greatest philosophers of the twentieth century had a definite mystical overtone to what he was doing. So you may or you may not have heard of Wittgenstein, certainly one of the greatest twentieth century’s philosophers. If you read the only book that he published in his lifetime, the Tractatus, that ends by saying “I’ve shown you all I can show; there’s more but you can’t say it.” So it’s a direct appeal to the ineffable. Ineffability and direct experience is not alien to the Western philosophical tradition. So to say that these things have religious aspects or some mystical aspects, therefore they’re not philosophy, is just a non-sequitur.’

On 01.03.09, in reply to a question from you, Stephen Gaukroger said:

‘I think a lot of the motivation for developments in science in the seventeenth century, particularly the late seventeenth century, are driven by developments in natural theology, that’s to say particularly in England for example, and this is a view to which Newton was very sympathetic, the idea is that you have these two sources of knowledge, still unreconciled from the beginning of the thirteenth century, namely religion and science, and the thing to do is to triangulate them so that you can sort out the wheat from the chaff, and the idea is that there is just a single truth: both these discourses aim at truth, so let’s triangulate them, get them fixed on the same thing so that we can work out what’s true and what’s false in each of them, and in the process, build up something that’s much stronger than either of them taken individually.’

Your program on 04.04.09 was on Hypatia of Alexandria and Neoplatonism. The blurb stated:

‘This week, we look at the woman and the heritage of what is probably the longest-standing philosophical tradition in Western civilisation: that rational yet mystical, sometimes Pagan, sometimes Christian, body of doctrines known as Neo-Platonism.’

On 11.07.09 Moira Gatens said of George Eliot:

‘I think at the time that she’s writing and Feuerbach are writing, the relationship between theology…and philosophy was much stronger than it came to be in the twentieth century.’ A week later Clive Hamilton argued for a mystical view of the world.

Just as Gatens gave the standard and profoundly incorrect assessment of the current relationship between theology and philosophy, Priest, Deakin and Wildberg addressed elements of a theological current that suffuses Western philosophy and arts – that of apophatic or negative theology – mysticism. It is one of the two great pathways to ‘god’ in our culture (‘great’ because of their impact and because of the contributions to the arts done on their basis). The other, from which it is inseparable, is the distorted and limiting understanding and application of ‘reason’ (or as the Christians believe – ‘Reason’) which in the twentieth century was revealed in academic philosophy as ‘the linguistic turn’, divorced from a basis both in materiality and practice.

As a materialist (those who describe themselves as ‘atheist’ require ‘god’ for their self-description no less than do theists, while those who describe themselves as ‘physicalist’ or ‘realist’ cause me to think of a mouse trembling before a trap, the cheese on which is ‘materialist’, the trap being ‘communism’…) I argue that the failure to even know about and understand this theological current let alone to teach it (the understanding of it, the analysis of it) as fundamental to our culture, as fundamental to moving forward in the most rounded way (distinct from Lloyd’s Man of Reason) is the most massive failure, the most massive display of determined ignorance, dishonesty and servility to the dominant ideology by generations of academics – those in philosophy and the arts hold the greatest responsibility.

Guthrie wrote that the strict meaning of ‘philosophy’ is ‘the search for knowledge’ and it is to knowledge not to a subject pervaded by a concealed priesthood (or in the case of Gaukroger – overt) that my allegiance lies. If you have a similar regard for knowledge and would like to contribute to the exposure of timeservers on a narrow goat-track leading from ivory towers behind cloistered walls, if you would like to use your program to contribute something truly new in this country to knowledge and philosophy, you might do your best to get Wiilliam Franke from Vanderbilt University on your program and interview him regarding his two volume anthology On What Cannot Be Said. These two books clearly reveal the impact of ‘god’ and mysticism on our culture, on academic philosophy – right up to the present.

Franke, himself imbued with academicism, does not realise what he has done. Rather than, as he sees it, taking philosophy into ‘new areas’, he has laid bare the priesthood of an ancient current.

I urge you to interview him, and by so doing, contribute to doing likewise.

I have tried for twenty five years in this dozy and servile culture to get academic support towards my analysing and exposing the impact of this current on the visual arts – and to date have met with consistent ignorance and had very qualified success. I know of no university in this country where (in terms of an impact comparable with that of Plato and Aristotle) one of the greatest philosophers in the West – Plotinus – is taught. It is an outrage against intellect, an utter failure in social responsibility by time-serving academics.

Kant wrote in the preface to the second edition of his Critique of Pure Reason that he had found it necessary to deny knowledge in order to make room for faith. I recall Wittgenstein, in an even more miserable tenor, writing in the Foreword to his Philosophical Remarks that he would have dedicated it to God but people would not have understood. Is this acceptable to you?

In the Routledge Companion to the Study of Religion excerpted in the reader for this year’s ‘Christianity as a Global Religion’ course at the University of Sydney it states: ‘One cannot ‘study’ mystics, except to the extent that they are prepared to write or speak about their experiences. There was however no lack of such material…’ True. This study is done in philosophy and the arts at every university in this country where these mystics are taught, but they are called ‘great thinkers’ and their experience is bounded by the limits of language banished from the Word.

Just as Cato the Elder argued ‘Carthago delenda est‘, I argue that the concealed priesthood particularly in philosophy but also in the arts must be flushed into the open, to unshackle the potential of the most advanced organisation of matter yet known to us anywhere in the universe – what we all have between our ears.

The title of your last Philosopher’s Zone asks ‘What makes a world class philosophy department?’ You are in a position to contribute to that answer and thereby to those with a passion for knowledge and progress.

Regards,

Philip Stanfield

* * *

To Alan Saunders, ‘The Philosophers Zone’, copied to Phillip Adams, ‘Late Night Live’, ABC Radio National, 11.06.11: ‘Plotinus and what cannot (but must) be said’

Hello Alan,

Congratulations for having finally done a show on Plotinus. Now move from the safe and distant past to the present and do a show on the impact of Neoplatonsim and mysticism on modern and current Western philosophy and culture. You could take Kant and any of the German idealists, the ‘genius’ and mystic Wittgenstein, Heidegger, Derrida etc. Take your pick. Contribute to exposing the concealed priesthood in philosophy – of which the Neoplatonic ‘priest’ Nietzsche wrote – and which is a massive impediment to the acceptance of our rapidly growing objective knowledge of the world.

Interview William Franke of Vanderbilt University who wrote a groundbreaking two volume anthology On What Cannot Be Said: Apophatic Discourses in Philosophy, Religion, Literature, and the Arts, exemplifying the impact of mysticism on our culture up to the near present. Or perhaps Mark Cheetham at the University of Toronto, who in 1991 published The Rhetoric of Purity: Essentialist Theory and the Advent of Abstract Painting – on the impact of Neoplatonism on Cubism – the pivotal moment of modernist art – both books met by thunderous silence in this dozy, servile and provincial culture.

Regards,

Phil Stanfield

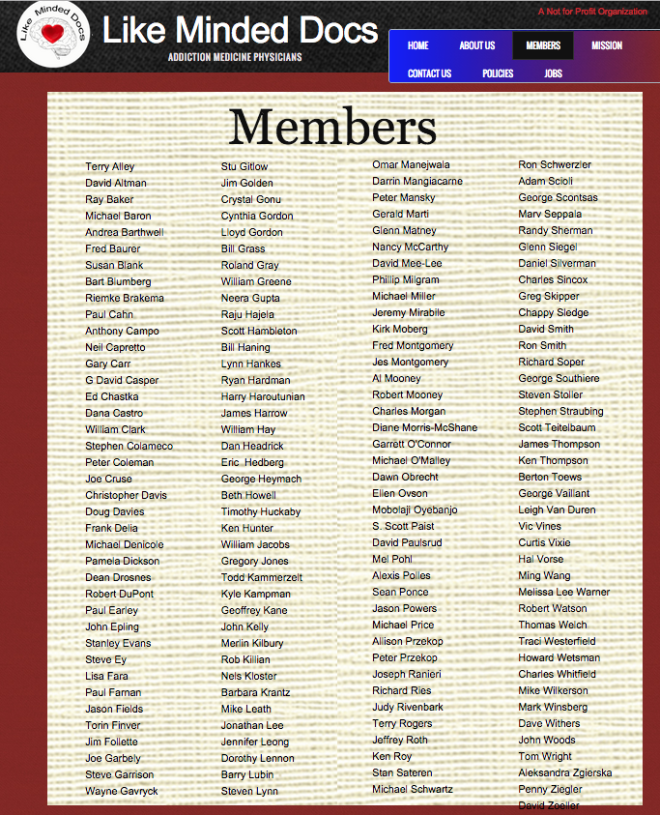

Images: top/bottom