Michelangelo, ‘The Young Slave’, marble, c. 1530-34, Galleria dell’Accademia di Firenze, Florence

‘…since Kant, transcendentalists of every kind have once more won the day – they have been emancipated from the theologians: what joy! – Kant showed them a secret path by which they may, on their own initiative and with all scientific respectability, from now on follow their “heart’s desire.” ’1

When we begin to study a text, we place our craft on a flow of words and are borne away. Are we won by their cogency? Or convinced by their force – by the impulse from their origin? Might we know them by the friends they keep, and by the deeds they commit upon us? Or do we engage with them and seek the contradictions – where the eddies, the cross movements, and the undertow – where the richer signs of life? …And to what are we blind, and why?…

We have understood Nietzsche, a man who wrote so much on the relation between form and content, largely according to his will. His writing on and against philosophical idealism sustains his work – he boasted that he had risen above that current running from Plato, through Christianity (‘Platonism for the people’, for which he felt the most bitter antipathy) to Hegel, Kant and Schopenhauer.2 He told us that Dionysus and Apollo overthrew this sickly orientation, that perspective should replace universals, that binary oppositions are false, and that the best art is synonymous with creativity, life and truth. And we welcomed his perspective.

Evocative of Proverbs 1: 20-31, Diogenes the dog in search of an honest person and Macbeth, Nietzsche’s madman entered the market place, lantern in hand, and cried words which have echoed through a much larger marketplace – ‘God is dead’. If not a shout of victory, these words convey the stamp of finality, emphatic in their simplicity. But why have they been ripped from their context, why has their meaning been torn from them, and both context and meaning discarded?

‘God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. How shall we, the murderers of all murderers, console ourselves? That which was holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet possessed has bled to death under our knives – who will wipe this blood off us?…Must not we ourselves become gods simply to seem worthy of it?‘ (my Italics)3

This quotation indicates how Nietzsche ‘solved’ his primary concern, the problem of God(’s death). Having willed His death in eternity…Nietzsche resurrected (created) Him in the temporal flesh. He brought back to earth and maintained in ‘life’ that which he attacked Plato and Christianity for having sent beyond. But it was to an earth beyond time, the life of ‘mind’.4 And he proselytised God in the name of another faith – his own creation, Dionysus.5

Nietzsche’s Dionysus and Apollo arose from a chain of inspiration originated by Plato, which has continued across generations, with inevitable developments and variations in emphasis. The Timaeus, a dialogue from Plato’s ‘middle’ or ‘late’ period, and generally and mistakenly regarded as a minor work, is his attempt to give a scientific explanation for the divine creation of this world – for that reason alone positioning it as a major work by him. In it is written an encapsulation of a process and purpose which is of the greatest importance to Western philosophy, Christian theology and Western art theory and practice

‘And (the Demiurge) gave each divine being two motions, one uniform in the same place, as each always thinks the same thoughts about the same things, the other forward, as each is subject to the movement of the Same and uniform; but he kept them unaffected by the other five kinds of motion, that each might be as perfect as possible.’6

This little group of words summarises the dual yet undifferentiated pathway Plato established between perfection, its divine medium, and creation; it asserts that creation and ‘thought’ in its motion are equivalent; it defines the nature of that process. The motions of his divine beings differ from those of the sensory world, they are effects of the soul in its activity.

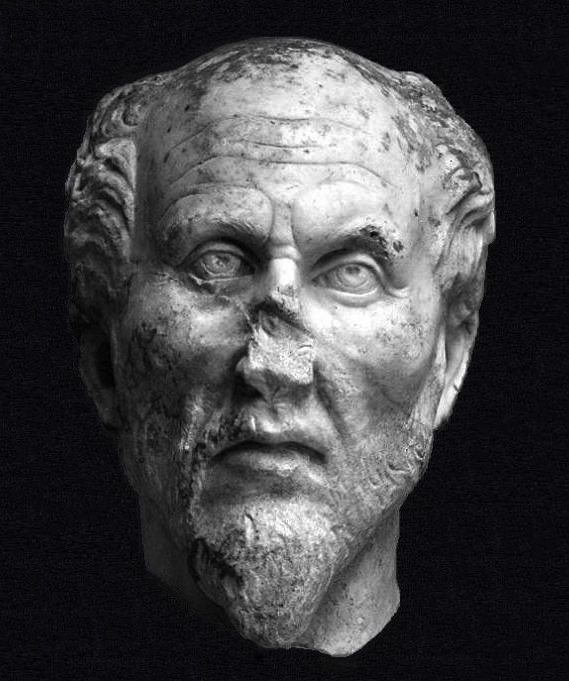

Plotinus’ mystical and emotive development on this (on the Soul’s contemplation of and desire for its source, his development of the realm of Forms into that of Intellect, and differentiation between its lower and higher aspects as the ascending Soul’s activity quickens, culminating in its unity with its source, his hypostasis of the One – which he defined as the greatest activity in the greatest stillness) was absorbed into Christian theology and Western philosophy as the methods of contemplation of form and (the movement through) desire, passion and the emotions, toward union with that which was desired (God).

These methods underlie Kant’s notions of the beautiful and the sublime,7 they echo in Schopenhauer’s writing and recur in his aesthetics8 – and again in Nietzsche’s Apollinian and Dionysian.9 As Plato’s Demiurge created the world and gave it form, as Plotinus’ Soul brought form from the far more ‘real’ universe of Intellect to Intellect’s eternal creation in matter, as the God of Christianity created the world to which He sent His Son as the embodiment of the Holy Spirit, so Dionysus eternally creates the world and gives of himself through the beauty of Apollinian form (which Nietzsche applied to appearance). Demiurge, Soul, Jesus and Dionysus are the media, ‘mind’ the message.10

For Nietzsche, the ‘tragic’ artist attains the Dionysian state through Apollinian apotheosis, the perfecting of man’s self.11 Obsessive self-love has its justification.12 Nietzsche emphasised the fecundity of Dionysus, destroying as he eternally creates – in so doing he drew from the work of Plotinus, who had an immense impact on Nietzsche’s own thought and of whom it was written that because of his mysticism, he has been a greater inspiration for Western philosophy than even Plato13

‘…the tragic artist…creates his figures like a fecund divinity of individuation…and as his vast Dionysian impulse then devours his entire world of phenomena, in order to let us sense beyond it, and through its destruction, the highest artistic primal joy, in the bosom of the primordially One.’14

The notions of vitality and creativity are fundamental to Plotinus’ philosophy. Not only are Intellect and particularly its source, the One, overflowing with activity, there is in Intellect an ‘…endlessness for ever welling up in it, the unwearying and unwearing nature which in no way falls short in it, boiling over with life…’15 The language Plotinus used to describe this excess of life resonates in Nietzsche’s description of Dionysian creativity.16 Creation is not for its own sake, but to produce objects of ‘vision’, to enable knowledge and ultimately the unity of seer, seeing and seen.17

Even Nietzsche’s description of man’s perfecting of himself

‘(In a Dionysian state, man) is no longer an artist, he has become a work of art: in these paroxysms of intoxication the artistic power of all nature reveals itself to the highest gratification of the primordial unity. The noblest clay, the most costly marble, man, is here kneaded and cut, and to the sound of the chisel strokes of the Dionysian world-artist rings out the cry of the Eleusinian mysteries…Do you sense your Maker, world?’18

is shaped not by Kant’s hand of nature, but by that of Plotinus, who commanded, in reply to the question ‘But how are you to see into a virtuous Soul and know its loveliness?’

‘Withdraw into yourself and look. And if you do not find yourself beautiful yet, act as does the creator of a statue that is to be made beautiful: he cuts away here, he smoothes there, he makes this line lighter, this other purer, until a lovely face has grown upon his work. So do you also: cut away all that is excessive, straighten all that is crooked, bring light to all that is overcast, labour to make all one glow of beauty and never cease chiselling your statue, until there shall shine out on you from it the godlike splendour of virtue, until you shall see the perfect goodness surely established in the stainless shrine…the Primal Good and the Primal Beauty have the one dwelling-place and, thus, always, Beauty’s seat is There.’19

Consistently, this current in philosophy is not driven by a will to life in this world but to one, as the hero in Dickens’ Tale of Two Cities said as he mounted the scaffold, in ‘a far better place’. What connects Plato, Plotinus and Nietzsche in this is their artistry, their immense sensitivity to the creative process and therefore their intense spirituality.

But they theorised about spirituality not as a fundamental quality of community but only of the male self and its Soul. They were unable to reconcile the elements of their brain’s functioning (from the emotional and non-discursive to cognition) both internally and to the world in which they lived.20 Their philosophies, ostensibly developed as a guide to life, grew in reaction to it. They direct away from life. Plotinus concluded his Enneads

‘This is the life of gods and of the godlike and blessed among men, liberation from the alien that besets us here, a life taking no pleasure in the things of earth, the passing of solitary to solitary.’21

The metaphor of flight illustrates their desire to break free from the gravity of objective reality – the flight of the poet in the Ion, the flight of the Soul in the Enneads, the flight of angels in Christianity, the flight of man in The Birth of Tragedy.22 This flight was aided by the non-discursive tools of intuition23 and, as Nietzsche was the first to acknowledge, the self-deceptive art of lying

‘…there is only one world, and this is false, cruel, contradictory, seductive, without meaning – A world thus constituted is the real world. We have need of lies in order to conquer this reality, this “truth,” that is, in order to live…To solve it, man must be liar by nature, he must be above all an artist…This ability itself, thanks to which he violates reality by means of lies, this artistic ability of man par excellence – he has it in common with everything that is. He himself is after all a piece of reality, truth, nature: how should he not also be a piece of genius in lying!…In those moments in which man was deceived, in which he duped himself, in which he believes in life: oh how enraptured he feels! What delight! What a feeling of power! How much artists’ triumph in the feeling of power! – Man has once again become master of “material” – master of truth! – …(man) enjoys the lie as his form of power.’24

Nietzsche wrote

‘An artist cannot endure reality, he looks away from it, back: he seriously believes that the value of a thing resides in that shadowy residue one derives from colours, form, sound, ideas; he believes that the more subtilised, attenuated, transient a thing or a man is, the more valuable he becomes; the less real, the more valuable. This is Platonism, which, however, involved yet another bold reversal: Plato measured the degree of reality by the degree of value and said: The more “Idea,” the more being. He reversed the concept “reality” and said: “What you take for real is an error, and the nearer we approach the ‘Idea,’ the nearer we approach ‘truth.’” – Is this understood? It was the greatest of rebaptisms; and because it has been adopted by Christianity we do not recognise how astonishing it is. Fundamentally, Plato, as the artist he was, preferred appearance to being! lie and invention to truth! the unreal to the actual! But he was so convinced of the value of appearance that he gave it the attributes “being,” “causality” and ‘goodness,” and “truth,” in short everything men value.

The concept of value itself considered as a cause: first insight.

The ideal granted all honorific attributes: second insight.’25

In the above, Nietzsche stated his belief that the artist cannot ‘suffer’ reality and that there is a profound connection between the artist, Plato and the Christian. He wrote that this connection, developed by Plato, opposes the equivalents of Idea or form (as Apollinian appearance), lie and the unreal, to being, and the actual. He tied their retreat from reality to the creation of and faith in a higher one in ‘mind’. For Nietzsche, Apollo and Dionysus were the gods bringing form and content to his new and lonely faith – a faith in which he was torn, as Plato revealed of himself in his writing of the Timaeus.

Nietzsche’s philosophy has much to offer, not least because it details the tension in his thought between life and Life, between perspective and religious vision. That he was a man of ‘god’, no less than his father and both grandfathers, who were all ministers in the Lutheran faith, he could not have denied. That his faith was strongly flavoured by the Christianity he despised he would have rejected, but it underpins his mask of the myth of Oedipus

‘Sophocles understood the most sorrowful figure of the Greek stage, the unfortunate Oedipus, as the noble human being who, in spite of his wisdom, is destined to error and misery but who eventually, through his tremendous suffering, spreads a magical power of blessing that remains effective even beyond his decease.’26

and his greatest mask, his ‘counterdoctrine’ of Dionysus

‘One will see that the problem is that of the meaning of suffering: whether a Christian meaning or a tragic meaning. …The god on the cross is a curse on life, a signpost to seek redemption from life; Dionysus cut to pieces is a promise of life: it will be eternally reborn and return again from destruction.’27

Not only does Christianity teach that Christ on the cross is the symbolic promise of eternal ‘life’, as Dionysus was for Nietzsche a signpost to seek redemption from the life of objective reality, both the god on the cross (who was also ‘cut to pieces’) and Nietzsche’s creative interpretation of his own god embody Platonic and Neoplatonic influence.

Nietzsche never lost the ‘intense piety’ of his youth – he adapted it.28 He was a major figure in the development of twentieth-century Modernism, and as we contemplate art that bears his influence, we might think of him and his heritage not as he willed, but critically.29

The epistemological flow which I have addressed here – this pathway to perfection, this stairway to heaven – is intimately bound to patriarchal power. Plato was born into a prominent Athenian family with many political connections – his mother’s second husband was a close friend and supporter of Pericles. Porphyry wrote that Plotinus was ‘greatly honoured and venerated’ by the emperor Gallienus.

It is a current suffused with exclusions – the exclusion of the complexity and possibilities of life in this world from what has been redirected and appropriated to a ‘higher’ one, the exclusion of ‘the feminine’ from ‘the masculine’ – of the intuitive and non-linguistic from the discursive – the exclusion of women from power, the exclusion from true power of the majority by the minority. The content of this current constitutes the core of the visual ideology of capitalism and permeates capitalist ideology.

The creativity which most fully involves the range of our brain’s capacities is that which can stimulate the viewer to recognise and embrace the necessity of contradiction and to engage ethically with the one (theoretical) absolute – that of change in a material world. Such a view is diametrically opposed to the philosophical current discussed, which aims to stimulate the viewer to the denial of contradiction and change – ultimately to a commitment to ideological stasis – through an orientation towards and a desire for God the Father, God the Self.

Notes

1. In extracts from On the Genealogy of Morals (1887) Third Essay, Section 25. Trans. W.Kaufmann. New York: Vintage, 1969, 156. The ‘secret path’ which Nietzsche bestowed underlay creative respectability. ↩

2. ‘…the worst, the most tiresome, and the most dangerous of errors hitherto has been a dogmatist error – namely, Plato’s invention of Pure Spirit and the Good in Itself…this nightmare…It amounted to the very inversion of truth, and the denial of the perspective – the fundamental condition – of life, to speak of Spirit and the Good as Plato spoke of them…Christianity is Platonism for the “people”.’ From the Preface to Beyond Good and Evil: A Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future. (1886) In G.Clive. Ed. The Philosophy of Nietzsche. New York: Mentor, 1965, p.123. ↩

3. From the madman’s speech in The Gay Science. (1882) 125. In the Introduction by R.J.Hollingdale to Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra. (1883-1885). Trans. R.J.Hollingdale. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969, p.14. ↩

4. Nietzsche wrote about the ‘…rare ecstatic states with their elevation above space, time, and the individual.’ The Birth of Tragedy (1872) Section 21, in The Birth of Tragedy and The Case of Wagner. Trans. W.Kaufmann. New York: Vintage, 1967, p.124. ↩

5. ‘As a philologist and man of words (?!) I baptised it, not without taking some liberty – for who could claim to know the rightful name of the Antichrist? – in the name of a Greek god: I called it Dionysian.’ In ‘Attempt at a Self-Criticism’ (1886), Section 5, in The Birth of Tragedy and The Case of Wagner op. cit., p.24. Also: ‘Whoever approaches these Olympians with another religion in his heart, searching among them for moral elevation even for sanctity, for disincarnate spirituality…will soon be forced to turn his back on them, discouraged and disappointed. For there is nothing here that suggests asceticism, spirituality, or duty. We hear nothing but the accents of an exuberant, triumphant life in which all things, whether good or evil, are deified.’ ibid., Section 3, p. 41; ‘(Dionysus is) a deification of life…the religious affirmation of life’. The Will to Power (1901), Bk IV, 1052. Trans. W.Kaufmann. and R.J.Hollingdale. New York: Vintage, 1968. p.542; ‘I am a disciple of the philosopher Dionysus, and I would prefer to be even a satyr than a saint.’ (two gods and their ministers?) From the Preface to Ecce Homo: How One Becomes What One Is? (1888), Section 2, in G.Clive. Ed. The Philosophy of Nietzsche. op. cit., p.134. Christianity has long had a central place for the passage of Spirit into flesh in its own mythology, under the rubric ‘et incarnatus est’. And this arose from a complex and rich heritage which Nietzsche correctly traced to the immeasurable influence of Plato (obviously Plato was not the only source). ↩

6. Timaeus, 8, 40. ‘And he bestowed two movements upon each, one in the same spot and uniform, whereby it should be ever constant to its own thoughts concerning the same thing; the other forward, but controlled by the revolution of the same and uniform: but for the other five movements he made it motionless and still, that each star might attain the highest completeness of perfection.’ The Timaeus of Plato. Ed. R.D.Archer-Hind. New York: Arno, 1973, pp.131-133. Plato is too often simplistically remembered as having given us eternal Forms (Plato as an eternal Form?). This quotation also points to the importance and complexity of motion in his philosophy. Lee argued that a major concern of the Timaeus is human psychology and that ‘…as the first Greek account of a divine creation, containing a rational explanation of many natural processes, it remained influential throughout the period of the Ancient World, not least towards its end when it influenced the Neo-platonists and when its creator-god was easily assimilated by Christian thought to the God of Genesis.’ In his Introduction to Plato Timaeus and Critias. Trans. D.Lee. Harmondsworth: Penguin,1977, p.7. ↩

7. ‘…the feeling of the sublime involves as its characteristic feature a mental movement combined with the estimate of the object, whereas taste in respect of the beautiful presupposes that the mind is in restful contemplation and preserves it in this state.’ I.Kant, Critique of Judgement. Bk II, Analytic of the Sublime, 24. Trans. J.Creed Meredith. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1952, p.94. ↩

8. Consider his distinction between the methods of science and experience – the rational method which is alone of use in practical life and in science (the method of Aristotle) – and ‘the method of genius’ – which is valid and of use only in art (the method of Plato). ‘The first is like the mighty storm that rushes along without beginning and without end, bending, agitating, and carrying away everything before it; the second is like the ray of sun that calmly pierces the storm and is not deflected by it. The first is like the innumerable, violently agitated drops of the waterfall, constantly changing, never for an instant at rest; the second is like the rainbow, silently resting on this raging torrent.’ A.Schopenhauer, The World As Will And Idea. Book III, 36. (Abridged in One Volume) 1819. Trans. J.Berman. London: Everyman, 1995, p.109. His aesthetics, expounded in Bk III were overtly Platonic – simply, he believed the object of art is the Platonic Idea. ‘Raised by the power of the mind, a person relinquishes the usual way of looking at things…He does not allow abstract thought…to take possession of his consciousness, but, instead, gives the whole power of his mind to perception, immerses himself entirely in this, and lets his whole consciousness be filled with the quiet contemplation of the natural object…he can no longer separate the perceiver from the perception, but the two have become one…then what is known is no longer the individual thing as such, but the Idea, the eternal form…The person rapt in this perception is thereby no longer individual…but he is a pure, willess, painless, timeless subject of knowledge.’ Book III, 34, p.102; also ‘(Art) repeats or reproduces the eternal Ideas grasped through pure contemplation, the essential and abiding element in all the phenomena of the world…it plucks the object of its contemplation out of the stream of the world’s course, and holds it isolated before it. And this particular thing, which in that stream was a minute part, becomes for art a representative of the whole, an equivalent of the endless multitude in space and time. So art pauses at this particular thing; it stops the wheel of time, for art the relations vanish; only the essential, the Idea, is its object.’ Book III, 36, p.108. ↩

9. Nietzsche wrote of ‘…that splendid mixture which resembles a noble wine in making one feel fiery and contemplative at the same time.’ The Birth of Tragedy, Section 21, in The Birth of Tragedy and The Case of Wagner, op. cit., p.125. ↩

10. Nietzsche was very aware of the heritage on which he drew – he creatively blended its elements in his writing ‘…the whole divine comedy of life, including the inferno, also pass before him, not like mere shadows on a wall – for he lives and suffers with these scenes – and yet not without that fleeting sensation of illusion.’ The Birth of Tragedy, Section I, in The Birth of Tragedy and The Case of Wagner, op. cit., p.35. Here Nietzsche refers to Plotinus through Dante’s great Christian allegory of the Way to God – ‘to that union of our wills with the Universal Will in which every creature finds its true self and its true being.’ – from the Introduction by Dorothy L. Sayers, in Dante. The Comedy of Dante Alighieri The Florentine. Cantica 1: Hell. Trans. D.L.Sayers. London: Penguin, 1988, p.19 (in which Dante is guided by the shade of the poet Virgil and then led by the beautiful revelation of God through philosophy, Beatrice, to Paradise), and directly to the simile of the cave in the Republic. Sayers referred to the ‘cold passion’ of Dante’s style (p.42). It might have been better described as repressed. ↩

11. Nietzsche was consistent with the patriarchy of this philosophical current. In the Enneads, Soul, on its way to pure unity with itself, aspires to and unites with Intellect. ↩

12. ‘If we conceive of it at all as imperative and mandatory, this apotheosis of individuation knows but one law – the individual…’ The Birth of Tragedy, Section 4, in The Birth of Tragedy and The Case of Wagner, op. cit., p.46. In Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche wrote ‘Sense and spirit are instruments and toys: behind them still lies the Self…Behind your thoughts and feelings, my brother, stands a mighty commander, an unknown sage – he is called Self. He lives in your body, he is your body.’ and ‘Your Self can no longer perform that act which it most desires to perform: to create beyond itself. That is what it most wishes to do, that is its whole ardour.’ Thus Spoke Zarathustra. op. cit., pp.62, 63. Likewise, Plotinus’ philosophy is concerned with the creation and perfection of self: ‘If there had been a moment from which He began to be, it would be possible to assert his self-making in the literal sense; but since what He is He is from before eternity, his self-making is to be understood as simultaneous with Himself; the being is one and the same with the making, the eternal “bringing into existence”.’ Enneads VI,8,20. ↩

13. P. Henry, ‘The Place of Plotinus in the History of Thought’. In The Enneads. Third ed. Abridged, Trans. S.MacKenna. London: Penguin, 1991, xlii-lxxxiii. ↩

14. The Birth of Tragedy, Section 22, in The Birth of Tragedy and The Case of Wagner, op. cit., p.132. Plotinus wrote: ‘Is that enough? Can we end the discussion by saying this? No, my soul is still in even stronger labour. Perhaps she is now at the point when she must bring forth, having reached the fullness of her birth-pangs in her eager longing for the One.’ Enneads V,3,17. The same religious belief in creativity was held by another extremely influential voluntarist and vitalist contemporary of Nietzsche’s – Bergson, whose best known work is titled Creative Evolution (1907). Plotinus believed that through loving oneself in God, one becomes God, one becomes the Creator. ↩

15. Enneads VI,5,12. ↩

16. ‘…in order that being may exist, the One is not being, but the generator of being. This, we may say, is the first act of generation: the One, perfect because it seeks nothing, has nothing, and needs nothing, overflows, as it were, and its superabundance makes something other than itself…Resembling the One…Intellect produces in the same way, pouring forth a multiple power – this is a likeness of it – just as that which was before it poured it forth. This activity springing from the substance of Intellect is Soul…(which) does not abide unchanged when it produces: it is moved and so brings forth an image. It looks to its source and is filled, and going forth to another opposed movement generates its own image, which is sensation and the principle of growth in plants…So it goes on from the beginning to the last and lowest, each [generator] remaining behind in its own place, and that which is generated taking another, lower, rank…’ Enneads V, 2, 1-2. Nietzsche wrote: ‘(The aesthetic state) appears only in natures capable of that bestowing and overflowing fullness of bodily vigour: it is this that is always the primum mobile…“Perfection”: in these states (in the case of sexual love especially) there is naively revealed what the deepest instinct recognises as higher, more desirable, more valuable in general, the upward movement of its type; also toward what status it really aspires. Perfection: that is the extraordinary expansion of its feeling of power, riches, necessary overflowing of all limits.’ The Will to Power op. cit., Bk 3, 801, p.422. ↩

17. The points of focus Nietzsche created to enable his longed for ascent to Truth are the Dionysian reveller, the satyr and Dionysus: ‘Such magic transformation is the presupposition of all dramatic art. In this magic transformation the Dionysian reveller sees himself as a satyr, and as a satyr, in turn, he sees the god, which means that in his metamorphosis he beholds another vision outside himself…With this new vision the drama is complete.’ The Birth of Tragedy, Section 8, in The Birth of Tragedy and The Case of Wagner, op. cit., p.64. Compare Nietzsche’s words: ‘Only insofar as the genius in the act of artistic creation coalesces with this primordial artist of the world, does he know anything of the eternal essence of art; for in this state he is, in a marvellous manner, like the weird image of the fairy tale which can turn its eyes at will and behold itself; he is at once subject and object, at once poet, actor, and spectator.’ The Birth of Tragedy, Section 5, in The Birth of Tragedy and The Case of Wagner, op. cit., p.52, with the chain of inspiration in Ion and Plato’s use of the metaphor of sight in the Republic’s simile of the cave, in which the philosopher attains the supreme ‘vision’ – that of the absolute form of the Good (Bk VII 514-521), ‘the brightest of all realities’. ↩

18. The Birth of Tragedy, Section 1, in The Birth of Tragedy and The Case of Wagner, op. cit., p.37. ↩

19. Enneads I,6,9. Nietzsche responded powerfully to the same ‘intoxicated’ drive to ‘shape’ and control the self in Plato in whom ‘…as a man of overexcitable sensuality and enthusiasm, the charm of the concept had grown so strong that he involuntarily honoured and deified the concept as an ideal Form. Intoxication by dialectic: as the consciousness of exercising mastery over oneself by means of it – as as tool of the will to power.’ The Will to Power. op. cit., Book 2, 431, p.236. ↩

20. ‘Thrown into a noisy and plebeian age with which he has no wish to eat out of the same dish, he (‘who has the desires of an elevated, fastidious soul’) can easily perish of hunger and thirst, or, if he does eventually “set to” – of a sudden nausea. – We have all no doubt eaten at tables where we did not belong; and precisely the most spiritual of us who are most difficult to feed know that dangerous dyspepsia which comes from a sudden insight and disappointment about our food and table-companions – the after-dinner nausea.’ Beyond Good and Evil, Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future (1886), 282. Trans. R.J.Hollingdale. London: Penguin, 1990, p.213. Nietzsche’s writing details over and again the gulf he felt between himself and others: ‘I don’t want to be lonely any more; I want to learn to be human again. Alas, in this field I have almost everything still to learn!’ From a letter to Lou Salomé, 2 July 1882. From the Introduction by R.J.Hollingdale to Thus Spoke Zarathustra. op. cit., p.21. ↩

21. Enneads VI,9,11. ↩

22. ‘…(man) has forgotten how to walk and speak and is on the way toward flying into the air, dancing…he feels himself a god…’ The Birth of Tragedy, Section 1, in The Birth of Tragedy and The Case of Wagner, op. cit., p.37. ↩

23. ‘(Dionysian) music incites to the symbolic intuition of Dionysian universality…’ The Birth of Tragedy, Section 16, in The Birth of Tragedy and The Case of Wagner, op. cit., p.103. ↩

24. The Will to Power. op. cit., Book 3, 853, pp.451-452. ↩

25. Ibid., Book 3, 572, p.308. ↩

26. The Birth of Tragedy, Section 9, in The Birth of Tragedy and The Case of Wagner, op. cit., p.67. ↩

27. The Will to Power. op. cit., Book 4, 1052, p.543. ↩

28. I use Hollingdale’s expression, in his Introduction to Thus Spoke Zarathustra. op. cit., p.12. Also: ‘What the Christian says of God, Nietzsche says in very nearly the same words of the Superman, namely: “Thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, for ever and ever.”’ ibid., p.29. ↩

29. ‘Art raises its head where creeds relax. It takes over many feelings and moods engendered by religion, lays them to its heart, and itself becomes deeper, more full of soul, so that it is capable of transmitting exultation and enthusiasm, which it previously was not able to do.’ From Human, All-Too-Human. A Book for Free Spirits. (1878) vol. I, 150, in The Philosophy of Nietzsche. op. cit., p.516. ↩

Image