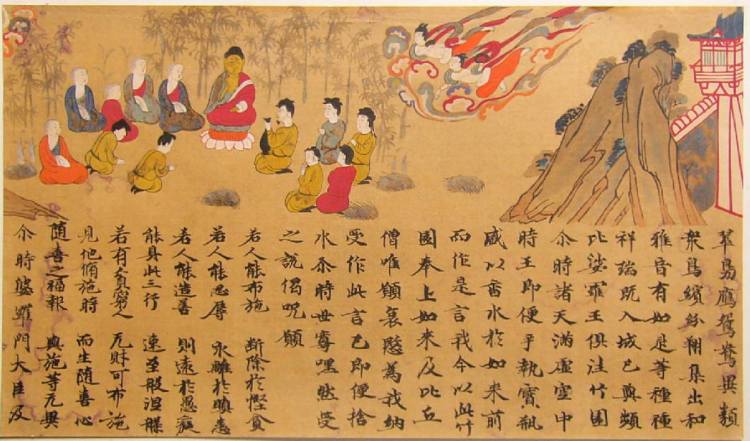

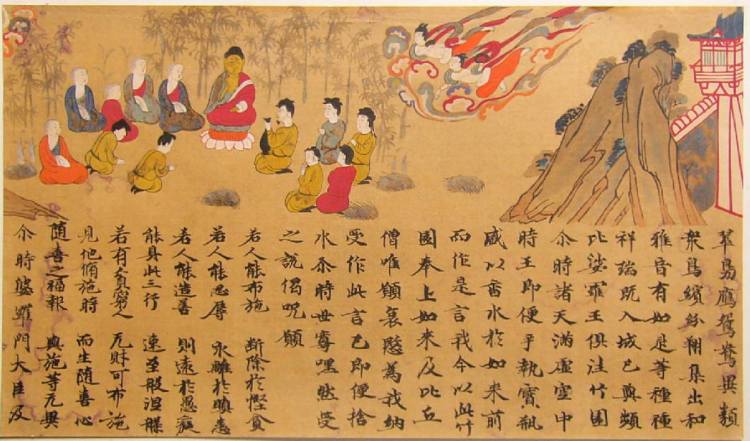

‘The Illustrated Sutra of Cause and Effect’, ink, colour on paper, handscroll, 8th century, Japan. Artist not named. Woodblock reproduction published in 1941, University Museum, Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music, Tokyo.

* * *

What runs through skepticism is a differentiation between philosophy as abstract reason or contemplation and a world of practical engagement – the world of ‘the common man’. Barnes defends Empiricus’s rejection of causality from his philosophy but acceptance of it in his discussion of the events of ‘ordinary’ Life, as Common Sense:

‘Sextus makes no attempt to avoid that ordinary vocabulary, the causal import of which he must surely have recognised. More specifically, Sextus from time to time permits himself an overtly causal sentence: a wound to the heart will cause death; motion and rest must have causes; good things may be the cause of misery.’23

Barnes writes that ‘Sextus’s causal utterances are not embarrassing flaws on the smooth body of his philosophical system…For Sextus presents himself as the champion of what he calls Life, bios. Life is contrasted with Philosophy.’24 Life ‘represents the wisdom of the plain man who is uncorrupted by esoteric and presumptuous speculation…the Skeptics are friends of Common Sense’25 And no doubt of the Common Man.

Empiricus wrote that it is easy to reject causality – ‘it is impossible to assert firmly that anything is a cause of anything’26 Barnes wrote ‘The Skeptic, then, attacks unobservable entities and judgements ostensibly made about them; he fixes his sights on what by nature escapes our sight, and on the Believers’ blind statements about such things’27

While the different treatment of causality in the realm of the philosopher and the world of the Common Man is most important, what underlies this (and much else) is the divorce of theory from its proper basis in practice and the absence in understanding of the necessary relation between the two.

In the latter, knowledge on the basis of sensory experience is intuitively accepted, in the former that connection is not questioned but denied because the relation between objective reality, sensation and brain is not understood.

To claim this difference is due to Empiricus’s acceptance of his society’s customs etc. does not deny the immense difference between philosophy and ‘bios’ – nor the revealing manner in which Barnes described it.

The materialist recognises the importance and nature of theorising to our knowledge of the world and distinguishes between the complete cause (the sum total of all the circumstances, the presence of which necessarily gives rise to the effect) and the specific cause. Causality is apprehended only through the revelation of essence and contradiction as the law of movement and development.

In his Meditations,28 Descartes did the same thing – first making himself comfortable, then severing philosophical (metaphysical) speculation from practical life29 and engaging in that human facility for self-reflection – consciousness reflecting on itself – to the furthest degree (which Plotinus had done in the first phenomenology and to the same extent, as Soul progressed through the hypostases of the Enneads, almost one and a half thousand years before) at the end of which, and in the most brazen manner – given his apparent agonising in the previous meditations – returned to ‘the world of the senses,’ stating he could clearly distinguish between dreaming and being awake and acknowledging his trust in the relations between his senses, memory and understanding.30

Yet no matter how well-reasoned the arguments of Descartes’ objectors (particularly those of Gassendi and Hobbes), they all missed the point – there can be no argument on the basis of or in relation to the physical world against Descartes’ meditations – because he utterly severed the physical from the ‘mental’ which comprised them.31 Descartes failed to counter skepticism because he too distinguished his contemplation from its basis in life and the world.32

Part three/to be continued…

Notes

23. Jonathan Barnes, ‘Ancient Skepticism and Causation,’ The Skeptical Tradition, Ed., Myles Burnyeat, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1983, pp. 149-203, 155 ↩

24. Ibid., 156 ↩

25. Ibid. ↩

26. Sextus Empiricus Outlines of Scepticism, op. cit., 149 ↩

27. ‘Ancient Skepticism and Causation’ op. cit., 157 ↩

28. ‘the title “Meditations” presents the work as something other than a chain of philosophical argumentation, and links it, rather, to religious exercises. …The “withdrawal of the mind from the senses” Descartes recommends as a precondition of the search for truth may well seem more reminiscent of spiritual techniques than of scientific enquiry.’ Introduction to Réne Descartes, Meditations on First Philosophy, Trans., Michael Moriarty, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2008, xiv-xv. ↩

29. ‘Let us then suppose that we are dreaming, and that these particular things (that we have our eyes open, are moving our head, stretching out our hands) are not true; and that perhaps we do not even have hands or the rest of a body like what we see.’ Ibid., 14. ↩

30. From Descartes’ Synopsis of the Meditations: ‘Finally (in the Sixth Meditation), all the reasons are put forward that lead us to conclude in the existence of material things: not that I think these are very useful when it comes to proving what they do prove, namely that a world really exists, and that human beings have bodies, and so forth, things which no one in their right mind has ever seriously doubted’ Ibid., 12. And from the end of his Sixth Meditation: ‘I need no longer fear that the things the senses represent to me in ordinary life are false: on the contrary, the hyperbolic doubts of these past days can be dismissed as ridiculous. …when things happen to me in such a way that I am distinctly aware of whence, where, and when they have come, and I connect the perception of them to the rest of my life, without any gaps, then I am well and truly certain that they are happening not in my sleep but when I am awake. Nor should I doubt even in the slightest degree of their truth, if after I have summoned all the senses, the memory, and the understanding to join in their examination, none of these reports anything that clashes with the report of the rest.’ Ibid., 63-64. ↩

31. ‘my doubts are metaphysical, and have nothing to do with practical life. Bourdin thus gives the unwary reader the impression that I am so mad as to doubt, in ordinary life, whether the earth exists, and whether I have a body.’ Ibid., 215. Stroud, writing in support of Descartes got it right: ‘how could a test or a circumstance or a state of affairs indicate to him that he is not dreaming if a condition of knowing anything about the world is that he knows he is not dreaming? It could not. He could never fulfil the condition.’ ‘The Problem of the External World’ op. cit., 15. ↩

32. Hume, who held that argument from experience must be without rational foundation was another who made the same distinction between philosophy and ‘common life.’ ‘He seems nevertheless to have felt few scruples over the apparent inconsistency of going on to insist, first, that such argument is grounded in the deepest instincts of our nature, and, second, that the rational man everywhere proportions his belief to the evidence – evidence which in practice crucially includes that outcome of procedures alleged earlier to be without rational foundation…Argument from experience should be thought of not as an irreparably fallacious attempt to deduce conclusions necessarily wider than available premises can contain, but rather as a matter of following a tentative and self-correcting rule, a rule that is part of the very paradigm of inquiring rationality – that one would think that other A’s have been and will be the same, until and unless a particular reason is discovered to revise these expectations.’ Antony Flew, Ed., A Dictionary of Philosophy, London: Pan, 1984, 172. Davidson likewise not only argued for a divorce of the senses from what takes place in consciousness – i.e. reason and belief (for him only beliefs can justify other beliefs since ‘beliefs are by nature generally true’) – but ‘abandoning the search for a basis for knowledge outside the scope of our beliefs.’ Like Descartes, he writes that our senses and observations might be lying to us – we can’t swear them to truthfulness. Donald Davidson, ‘A Coherence Theory of Truth and Knowledge’ in Epistemology An Anthology, op. cit., pp. 162, 156, 157. ↩

Image